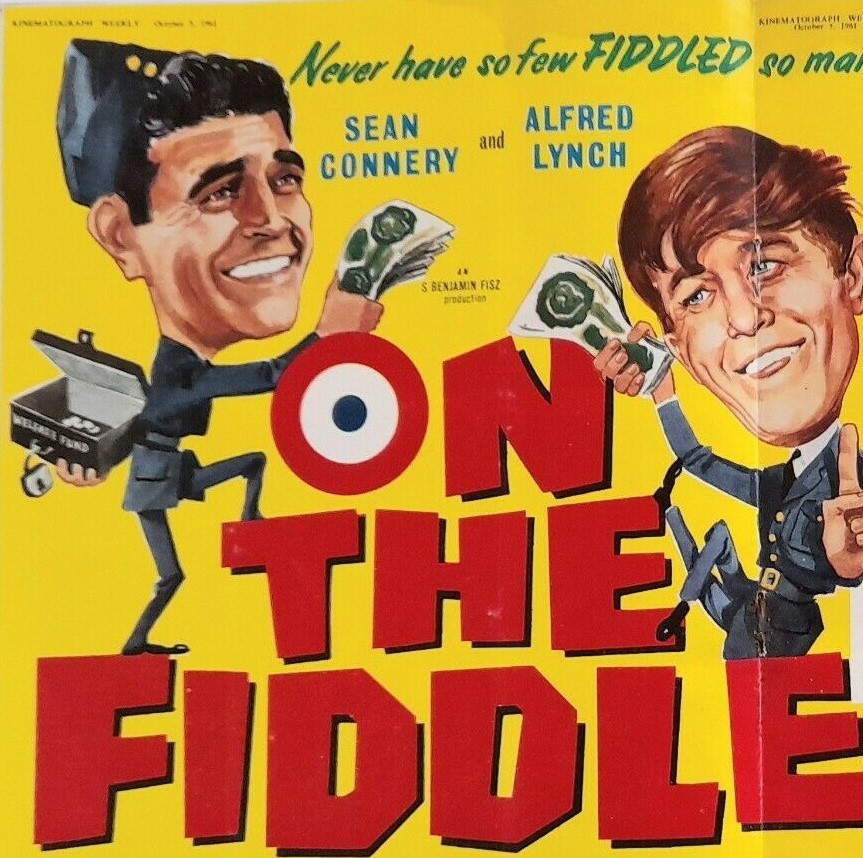

Unassuming but undeniably charming British World War Two comedy denied U.S. release until four years later when a savvy distributor jumped on the James Bond bandwagon. Primarily of interest these days for the opportunity to see a pre-Bond Sean Connery (Dr No, 1962) in action its merit chiefly lies in ploughing the same furrow, though with a great deal less pomposity and self-consciousness, as the later The Americanization of Emily (1964), of the coward backing into heroism.

Horace Pope (Alfred Lynch) is a scam merchant who only dodges prison by enlisting. Assigned to the RAF he teams up with Pedlar Pascoe (Sean Connery) and they embark on a series of schemes designed to keep them as far away from the front line as possible. It’s hardly an equal partnership, Pope dreams up the fiddles while Pascoe just falls in with them. It’s not dumb and dumber but a collaboration that goes no further back in the annals of movies than brain and brawn.

It’s certainly a cynical number, reflecting the boredom experienced by many of the Armed Forces backroom staff, the administrators whose inefficiency turns them into easy dupes, and the determination of soldiers to take advantage of every opportunity to bend the rules. It takes the unusual position of presenting the ordinary soldier as smart and every officer as a numbskull, an approach that would only have been possible 15 years after the war ended and in marked contrast to the determined heroism of other British war films – such intrepid stiff-upper-lip behavior a hallmark of the British version of the genre.

First stop is to run an operation issuing leave passes – for a price – and the sheer effrontery exhibited by Pope is a joy to behold. Next up is selling stolen meat on the black market.

While Pedlar is the wide-eyed camp follower, and more likely to forever sit on the sidelines, cheerful but shy, and only a few pratfalls away from being a bumbling idiot, they do make a good team. Being sent to France is more of a heaven-sent opportunity to increase their bankrolls than a hazardous wartime mission as Pope sells rations to the French. Eventually, of course, their various scams are rumbled and they are forced into battle.

The movie switches a bit more deftly into serious mode than the aforementioned The Americanization of Emily mostly because these are actual soldiers trained to be soldiers rather than an officer who landed a cushy number and whose main effort is to avoid combat. War is presented as horrific rather than comedy and it must have been the same experience for an ordinary soldier at the time, after months of inactivity suddenly thrust into the cauldron.

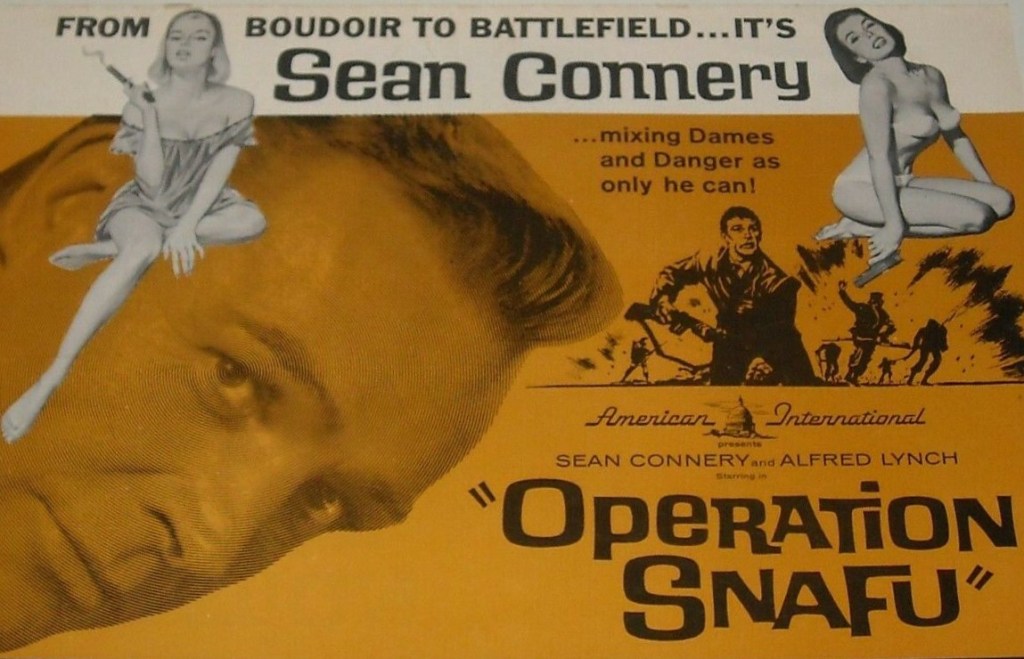

The picture moves at a brisk pace and is continually amusing if not particularly laugh-out-loud. You’ve probably seen most of the set-ups before but they are reinvented with an appealing freshness and briskness As a bonus there’s reams of British character actors and comedians – plus token American Alan King (who would appear in Connery starrer The Anderson Tapes, 1971) – along the way. The term “snafu” in case you’re interested, has a similar meaning to the “fubar” of Saving Private Ryan (1998).

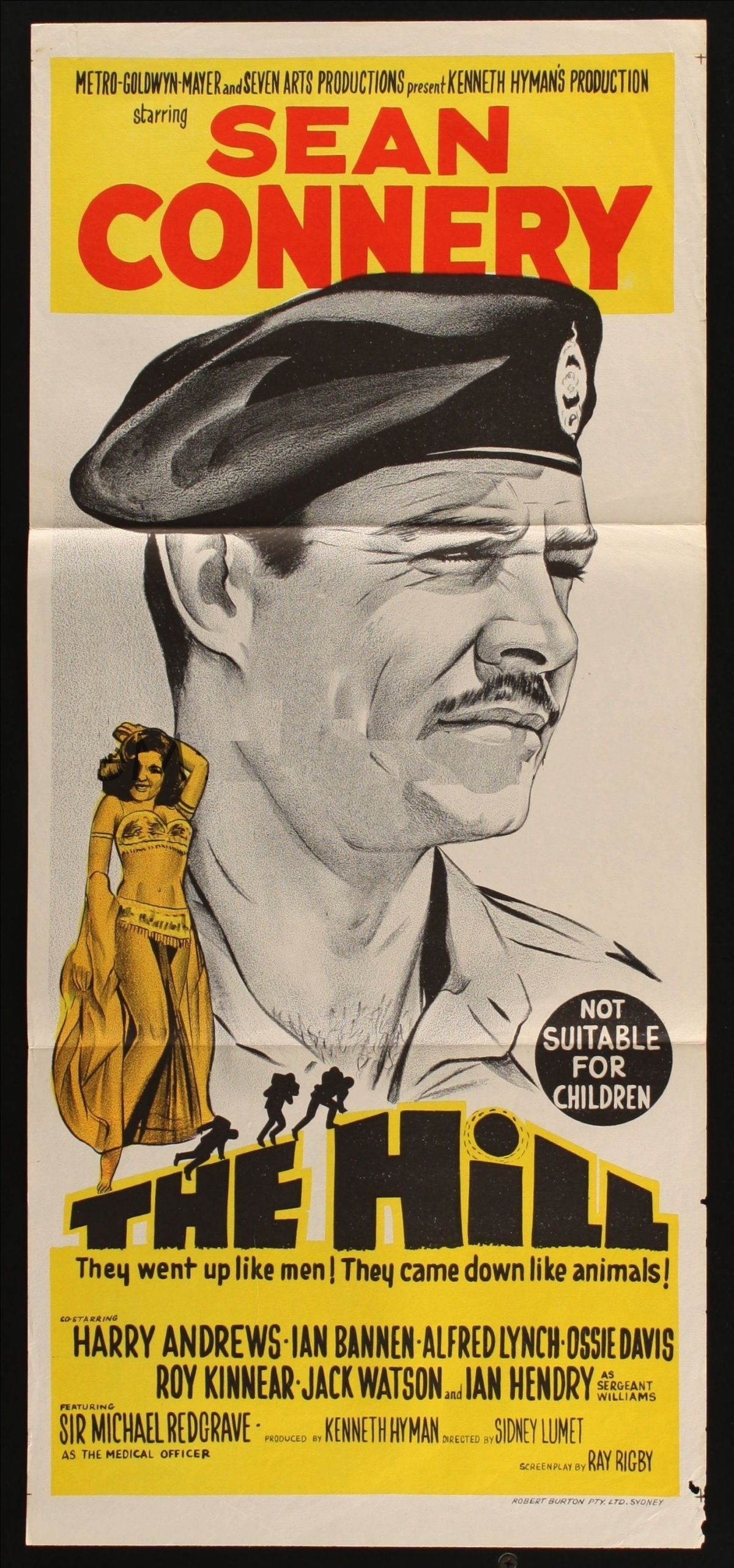

Alfred Lynch (The Hill, 1965) doesn’t milk the Cockney patter overmuch and he’s got a greater international screen appeal than the likes of the more English Sid James (Carry On films) or Norman Wisdom. Think a shiftier Sgt Bilko, if the Phil Silvers creation could be any more untrustworthy.

Connery’s performance is well worth a watch as a prelude to what was to come once his roles were tailor-made. He is an effortless scene-stealer, gifted in expressing emotion through his eyes, and although verbally Lynch dominates it’s difficult to take your eyes off Connery.

The roll-call of character actors includes Cecil Parker (A Study in Terror, 1965), Stanley Holloway (My Fair Lady, 1964), John Le Mesurier (The Moon-Spinners, 1964), Graham Stark (The Wrong Box, 1966) and Victor Maddern (The Lost Continent, 1968).

Cyril Frankel (The Trygon Factor, 1966) comfortably cobbles this together from a screenplay by Harold Buchman (The Lawyer, 1970, and who had ironically enough penned the picture Snafu in 1945) based on the novel Stop at a Winner by R.F. Delderfield.

When the box office supremacy of the Bond pictures was underscored by the reissue of the Dr No/From Russia with Love double bill in 1965, distributors, as had been their wont, racked the vaults for anything featuring Connery that could be re-sold to a willing public.

While there is a readily available DVD, this turns up on a regular basis, in Britain at least, on television.