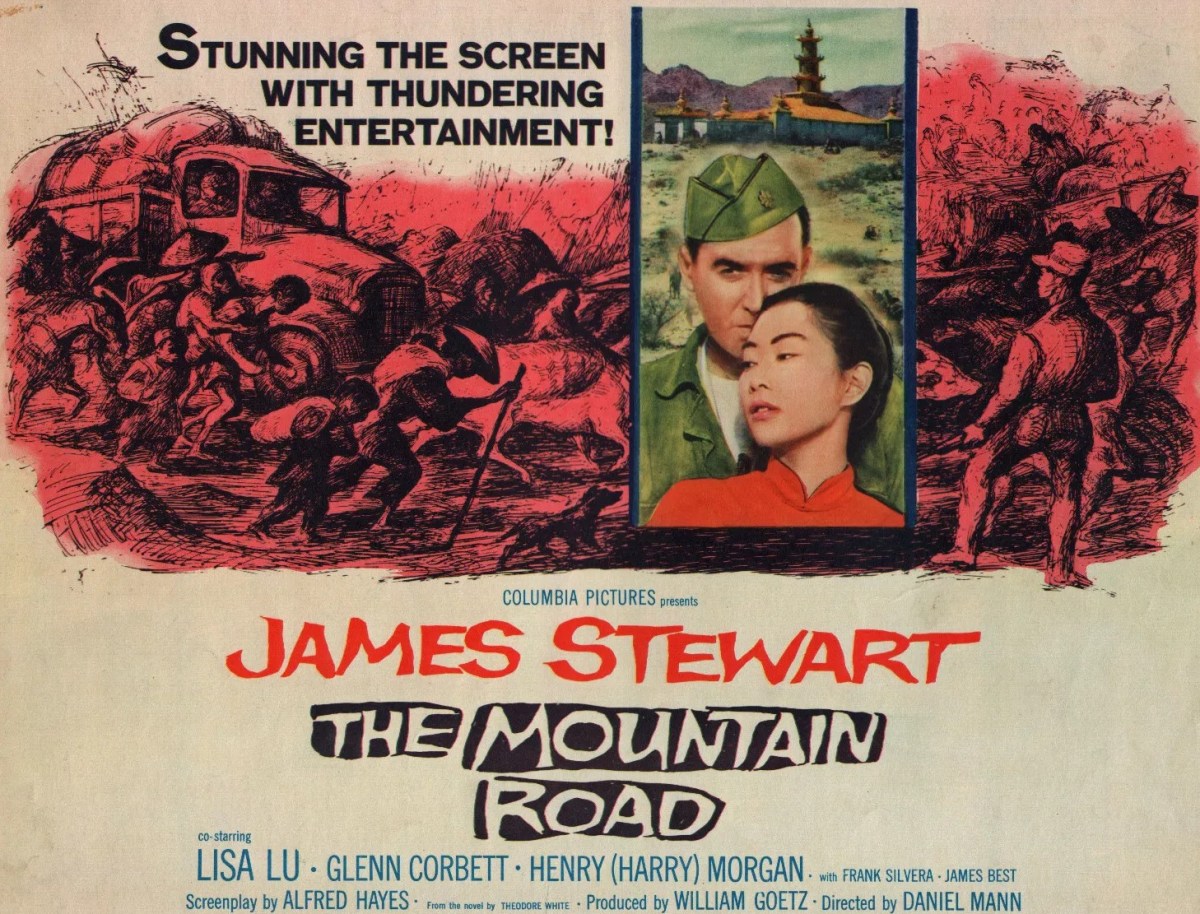

First film to deal with U.S. Army war crimes. Though here’s it’s tabbed as abuse of power but amounts to the same thing when it relates to the wanton killing of innocents. Not the first film to examine a commander totally unsuited to command – The Caine Mutiny (1953) would be your first port of call for that, although that was a career officer rather than a conscript. But the blistering under-rated Oscar-ignored performance by James Stewart (The Rare Breed, 1966) is easily comparable to the Oscar-nominated Humphrey Bogart.

And director Daniel Mann (A Dream of Kings, 1969) is helluva sly. He dupes the audience into thinking this is a mission picture, blowing up a massive ammunition dump to prevent it falling into enemy hands. And if you’re one for the easy action of explosions, this is for you, the kind of fireworks not seen till MCU entered the equation.

And here’s a line that’s going to knock you for six. “China and America are friends.” Say again? You what? As far as I can remember in all my decades of moviegoing, China has always been the enemy, either providing a succession of nefarious villains, or on the brink of starting a nuclear war, or just totally ungrateful for all the efforts the West has made bringing to the country Christianity and the western idea of civilization.

But it’s true. Before Communist China reared its ugly head, the U.S. and China were allies against the Japanese in the Second World War. But towards the end of that conflict, the Japanese had invaded and the Yanks were pulling out. Not wanting to leave anything behind for the enemy – like a huge arsenal or thousands of gallons of diesel – is the trigger for the story.

Except it’s not. Major Baldwin (James Baldwin) doesn’t have to go on any mission. His job is just to blow up a much smaller ammunition dump that’s easily accessible without the need to go on a long trek through the mountains. It’s his choice to take on the bigger job. There’s not even any pressure to do so. It’s entirely at his “discretion.” And you can see in the tone of his superior’s voice that it’s not such a good idea. He can just complete the small job and high-tail it out of there.

But Major Baldwin wants to experience command in action. He’s not a glory hunter in the normal sense but there’s definitely something off in a backroom soldier who’s got that on his wish list. It never occurs to him that there’s more to command than ordering about grunts, many of whom he considers “slobs,” and that the position comes with the task of making difficult decisions.

He’s got a very small team, chief among whom is Sgt Michaelson (Harry Morgan) and translator Collins (Glenn Corbett). Chinese officer Col Kwan (Frank Silvera) is meant to smooth his path and the widow of a Chinese general, Sue Mei (Lisa Lu), is thrown his way, initially you would guess to sweeten the load by becoming a love interest, but actually to become his conscience.

Just to fill you in on the background. China and Japan had been at war since 1937. After Pearl Harbor China became critical to US operations in the Pacific by tying down Japanese forces and after the fall of Burma the US airlifted supplies over the Himalayas.

Baldwin soon discovers that leadership equates to callousness. He has little sympathy for the refugees swarming over the mountain roads seeking sanctuary from the invading Japanese. He blows up a bridge and creates an impasse on the road to delay the Japanese without giving any thought to how that will endanger the natives.

He’s pretty inhuman in his treatment of one of his men, suffering, it later transpires, from pneumonia and might be taking all his cues from General Patton who hated all wounded soldiers. While he’s trying to convince the soldier to get back on his feet all the grunt can do is whimper, “Milk! Milk” like a child. Baldwin even sees little problem in stacking the ill man beside a corpse on the back of a lorry.

It would help if Baldwin had been trained in command, in making decisions, rather than picking faults everywhere and letting the pedantic side of his nature run wild. Sei Lei to some extent tries to rein him in, accusing him of blatant racism, treating the Chinese as if they were a lower form of humanity.

When he does relent and orders surplus food to be handed out one of his men is killed in the stampede. The last straw is Chinese bandits who kill and strip three of his men. So he leads a raid on a Chinese village, rolling a barrel of fuel stacked with dynamite down a hill to destroy the village and innocent villagers.

Up till then things were going along nicely on the romantic front, Sei Lei clinging to him when the massive ammunition dump goes up, and kissing on the cards. She’s westernized after all, spent a lot of time in America, well educated, and so easily a contender for marriage. But she tries to stop the barrel-rolling, telling him this action is unjustified, pure revenge.

He thinks she’ll accept an apology, that some madness came over him, he was consumed by power. But she’s having none of it.

Mission accomplished but human flaws exposed.

This isn’t the James Stewart you’ve come to expect, far from it. There’s certainly times in his career when he’s been mean or ornery and in his Hitchcock excursions a bit creepy, but he’s never been so awful as here, the guy desperate for power without knowing how to use it or draw the line. Purely in a technical capacity, working out where to plant explosives and plan a demolition, he’s in his element, but let him loose on human beings and he’s a loose cannon trying to rein himself in, stuck in a mess of his own making, unable to understand consequence. But sometimes even guilt isn’t enough.

This was an unlikely role for Stewart because, after his own experience in World War Two, a pilot in Bomber Command flying missions over Europe, he had turned down every war picture. Perhaps this movie reflected the guilt he felt of dropping bombs and knowing there would be civilian collateral damage, that sense of power over the powerless might equate to the feelings Baldwin has over the Chinese.

This is by far the most human character Stewart ever played, doing away with both the aw shucks everyman and the commanding often truculent cowboy, and instead portraying someone who’s way out of his comfort zone.

Ace scene-stealer Harry Morgan (Support Your Local Sheriff, 1969) is the pick of the support though Lucy Lu (One Eyed Jacks, 1961), being the conscience of the piece, has all the best lines.

Just as with A Dream of Kings, Daniel Mann takes a flawed individual and doesn’t hang him out to dry. But in retrospect, the war crime, of blowing up the innocent civilians, would not have received such a free pass, which puts a different slant on Baldwin. Alfred Hayes (Joy in the Morning,1965) wrote the script from the Theodore H. White bestseller.

Much to ponder.