Touching low-budget B-movie shot in black-and-white of a young man receiving his sexual education from an older woman. Motherless Vito (Scott Maxwell), the son of an apartment block super, is seduced by the older Iris (Lola Albright), three-time divorcee, looking for a son to mother.

This is not the transactional sex of The Graduate, and seduction is too strong a description for the yearning Iris whose advances are sensual and romantic, stroking Vito’s head, trapping his hand with her foot, and there is nothing clandestine about their affair either, no false names on a hotel register. They dally in the park, eat hotdogs, and he buys her flowers.

But as he experiences love for the first time, he also experiences more difficult emotions like jealousy and finds it difficult not just to cope with what seems like another man in her life, the wholesaler Juley (Herschel Bernardi), but the fact that she treats him with such contempt. Spoiler alert – well, not really, because you know from the off this is not going to turn out well – the affair ends when he discovers she is a stripper. And while she is left bereft, he now appears more attractive to girls his own age.

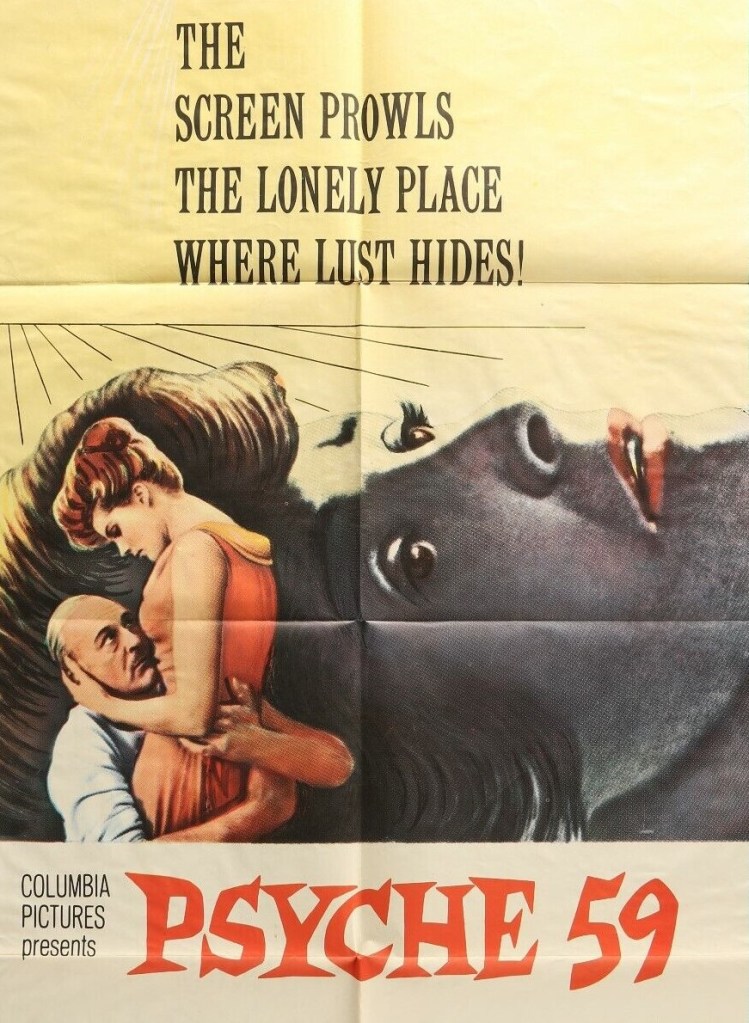

In contrast to the powerful emotions stoked up when the pair are together, director Alexander Singer (Psyche ‘59) fills us in on the rest of Vito’s humdrum life, working for his father during the school holidays, goofing off with his pals, and generally failing to make headway with girls his own age. But Iris’s life is not humdrum. Although she has a rule not to work in her own area, she breaks that to accommodate her estranged husband, whom she seems to tolerate, while at the same time drinking herself into oblivion to avoid any moves from Juley. Nor is she ashamed of her profession. It is an act, a job like any other, and provides her with a nice apartment.

Small wonder she treats men with contempt. Perhaps what she falls in love with is untainted innocence. In some senses she is adrift, at other times in full command. And her love for Vito is convincing.

It is full of incidentals. He gulps down ice-cream, she teaches him to drink one sip at a time, without being patronizing the father (Joe De Santis) tries to educate him to honor his inner feelings.

Lola Albright (Peter Gunn television series) carries off a difficult role very well indeed. Without laughs to help him out as it did Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate, Scott Maxwell is believable both as the youth growing into adulthood and the youth wanting to remain a youth with no adult responsibilities. The low-key performance of Joe De Santis is worth a mention.

While the picture no doubt attracted attention for the risqué material, which would have certainly given the Production Code pause for thoughts, it provided a more rounded picture than was normal at the time of a woman working in the sex industry, even if only in the stripping department. Iris did not fall into any of the cliches. She is presented as a woman first and foremost rather than a stripper.

Alexander Singer sticks to the knitting and doesn’t come unstuck. John Hayes (Shell Shock, 1964) wrote the screenplay based on the Burton Wohl bestseller.

Unusual variation on the theme.