At best, nifty piece of counter-programing, short on running time compared to the ballast-heavy bum-numbing three hours-plus of The Brutalist. At worst – where do we start? Maybe with the bald wig where you can see the join. Just part of the bombastic over-the-top zoppazaloola performance by Mark Wahlberg, deciding not to entertain a smidgeon of finesse or subtlety, not even of the John Malkovich (In the Line of Fire, 1993, Con Air, 1997) vintage, in his portrayal of a sadistic bisexual rapist murderer with a propensity for chopping off fingers and indulging in other anatomical atrocities.

The aim was, I guess, Narrow Margin on a Plane, though the confines of a cabin in a tiny plane leave little room for maneuver. And blow me down if the whole damn thing wasn’t shot over Alaska as the movie portends, but in Nevada, although I guess to the uninitiated one snow-capped peak looks very much like another. And blow me down number too, just when the tension (what tension?) should be ratcheting up to eleven, if we don’t take time out from chaining up the bad guy to allow our other more civilized bad guy to go all sentimental on us and want to do something good.

And that’s before we delve deep into a dumb back story about our cop being responsible for burning a prisoner to death after she went against all the rules of the profession and allow said female prisoner to take a shower, shackled to the bath to permit privacy, not expecting someone to lob a Molotov Cocktail into the bathroom. Your heart bleeds.

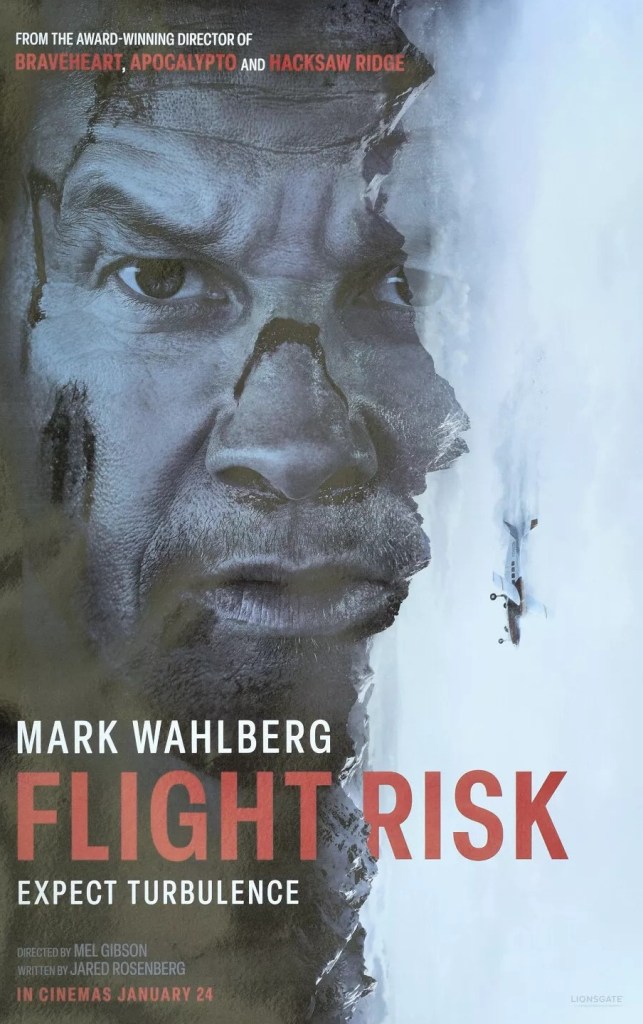

So, U.S. Marshal Madolyn (Michelle Dockery) in sore need of redemption after the prisoner-burning episode is escorting Winston (Topher Grace) from his hidey-hole near the Arctic Circle so he can appear as a witness in a Mafia trial, him being the mobsters’ accountant. Daryl (Mark Wahlberg) is their cocky pilot. Winston’s main job is to add laffs, by being just the kind of weak-minded entitled chap who took the easy route to riches rather than go to college and get a proper job. Madolyn has got other things on her mind beyond redemption and not liking the look of the cocky pilot.

She has sniffed out corruption in the department which might go as high as very high indeed, with a guy on the Mafia payroll, whom Winston, once he gets into his stride as a reformed criminal, is going to give up. All this by dint of her remote detection.

Or she could just be distracted by the rom-com elements of the plot. Did I mention there was romance? Our Madolyn is way too smart to fall for a dumbass like Winston and ain’t going to let a cocky hardhead like Daryl engage her in banter. But she’s a sucker for a sweet-talking off-stage fella who’s going to instruct her how to fly the plane once she’s incapacitated Daryl. He’s full of great information which I’ll bear in mind next time I’m on a plane coming in to land that’s run out of fuel. Guess what, it’s easier to land a plane if it’s run out of fuel. Phew, that’s a relief.

I’m generally all-in when it comes to hard-edged crime pictures with less-than-stellar casts as long as the action keeps coming and the plot makes some sense. This feels like they put out an all points bulletin for any idiotic plot handle they could find and when that didn’t work thought the casting would save them. Let’s get one of those top-class English lasses from Downton Abbey and put her through the mill and let’s get a fairly stellar action star and let him go off-piste.

In fairness, Michelle Dockery, who had already mined a tough streak in Godless (2017), isn’t bad, discarding all the girly girl prettiness in favour of no make-up no-nonsense toughness and twisting around seven ways to sundown to accommodate all the twists in the plot, even softening enough to indulge the romantic dreams of her off-stage lothario.

There’s maybe a chance this will turn into so-bad-it’s-good gold and if so it will be down to a demented performance by Mark Wahlberg (Father Stu, 2022), one of the few top stars, either by desire or financial necessity, to take risks with his screen persona. The problem is that his part is really a glorified cameo, the picture not so much revolving around his horrid horror-porn imagination, as the redemption-cum-rom-com focus of Michelle Dockery, the latest in a series of eye-gouging unlikely action heroines.

Directed by double Oscar-winning Mel Gibson (Hacksaw Ridge, 2016), no slouch himself, as an actor, in putting in a demented performance. Directed, without, I guess, the slightest notion of irony. Script by Jared Rosenberg in his screen debut.

But as I said, beats The Brutalist hands-down when it comes to lean running time (just 87 minutes).