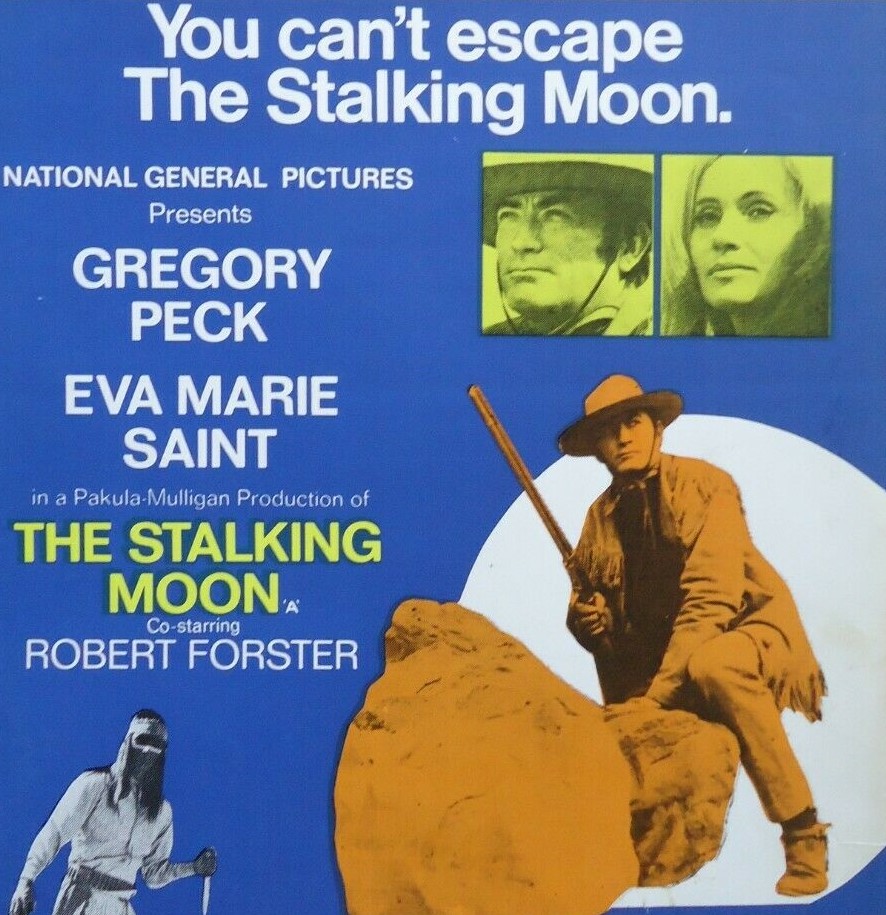

About-to-retire Indian scout Sam Varner (Gregory Peck) helps the U.S. Cavalry round up Indians to take to reservations. One of these is American Sarah Carver (Eva Marie Saint) who, with her Apache son, is attempting to escape her vengeful Apache husband Salvaje (Nathaniel Narcisco). Varner agrees to take her to the nearest stage coach post, and then to a train depot, and, finally, to his ranch in New Mexico where they enjoy a period of security. But wherever she goes, death follows, culminating in a shootout in the hills around his ranch.

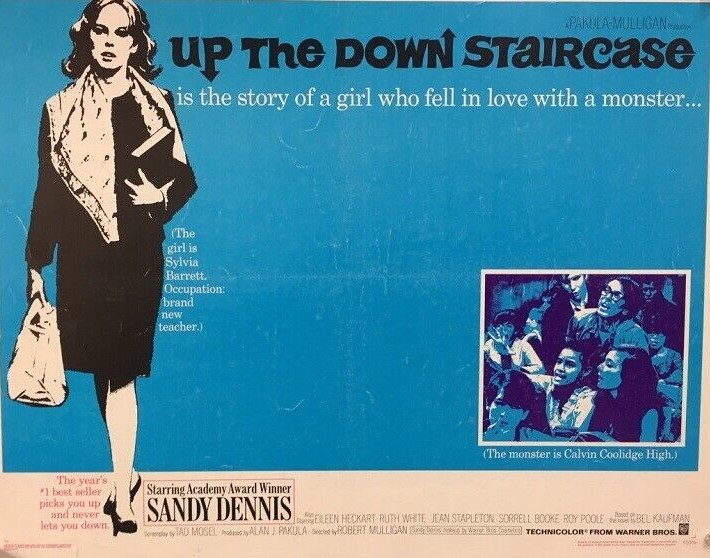

But the treatment by director Robert Mulligan (Up the Down Staircase, 1967) is far more complicated, often asking questions that cannot be answered, and placing the principals in situations that cannot be easily resolved. Sarah Carver has not gone running in order to find a man to save her; she does not think she can be saved and accepts the inevitable. She feels guilty for “lacking the courage to die,” of accepting Salvaje as her husband instead of dying along with the rest of her family when attacked a decade before by Indians.

She is weak in other ways, hiding the identity of her husband from the Army and everyone else in case she is abandoned. She shows no great bond with her son, who, several times, attempts to escape.

Sam Varner is very much an ordinary guy, just wanting to quit the Army and work his ranch. He is not the traditional extrovert western hero, nor the man who reluctantly takes up arms. He has no wish to get involved with Carver and each time he does agree to help it is with a time-limited condition attached and these scenes lack any sense of meet-cuteness, no romantic interplay hastening him to a decision, little expectation that either party is angling to fall in love.

It is practicality rather than intimacy that makes them share a blanket during a dust storm and he asks her to come to his ranch because he will get on with the work quicker if he has someone to cook. In fact, his honesty prevents that: he confronts her over the fact that she “put us out here knowing all the time that he’d come after us” and making her face the corpses of men who died because she hid the truth. He is honest with his emotions and he is determined (“I got a place to go and I’m going”). But he bears none of the normal western hero’s traits, neither a hard drinker, loner, or gunman. He is not gauche like James Stewart or malevolent like Clint Eastwood.

Even more unusual is the treatment of Salvaje. Despite the savagery of his actions, there is within him a sense of honor. He only chases his wife because she has stolen his son; there could be no greater affront to his dignity. The story is told from the point of view of the pursued i.e. Sarah Carver. But, by turning that perspective on its head, The Stalking Moon more easily fits into the category of revenge western, characteristically a picture concerning chase and pursuit by someone who has been wronged.

The director takes a bold step in the presentation of Salvaje. He is not seen at all in the first hour, then in just a few glimpses of a shape, his face only revealed at the climax. He is a ghost and a killing machine combined. Like a latter-day “Terminator,” he cannot be stopped, so skilful he evades capture, and relentless.

It is also, unusually for a western, a thriller. The tension mounts from the discovery, at the 10-minute mark, of Salvaje’s first three victims, all fully-armed soldiers, and the news, one minute later, that he single-handedly killed four troopers previously. At Hennessy, a staging post, when Varner and Carver go out into a dust-storm to search for her son who has run away, they return to find all dead. Everyone they left behind at Silverton, a train depot, is also killed.

Initially, Carver appears impatient, not willing to wait five days for an Army escort, but once she reveals who the boy’s father is, the reason becomes clear, and her desire for speedier transition creates more tension. Even in New Mexico, the death toll mounts, once Salvaje arrives. Now the trap closes in on them. Even the ranch house cannot prevent Salvaje from sneaking in and kidnapping his wife, leaving her for dead outside.

When Varner and a fellow scout, the half-breed Nick Tana (Robert Forster), attempt to turn the tables on Salvaje and track him down, it ends in Tana’s death. Although most of the tension comes from the will- he-won’t-he dynamic, there are number of Hitchcockian touches such as offscreen sound cues triggering alarm in characters. In two instances, a door provides shock.

Far from providing the expected relief, the ranch house merely provides a claustrophobic setting for the characters. Varner is trapped with an inarticulate pair. Instead of arrival at the ranch house precipitating emotional response and romantic interlude, as would be par for the course for other westerns, Varner finds himself stuck with a woman who refuses to talk and a boy who does not understand a word he says. The seven-minute scene where he sits down to eat and then has to virtually command mother and son to join him and encourage them to talk even if it is just to say “pass the peas” is one of the most awkward ever filmed.

The movie is so darned awkward that you never laugh even at the few moments of comedy, the complicated issuing of train tickets, Varner keeping up a one-sided conversation at the table, Nick’s attempts to teach the boy poker. Relationships are more likely to remain in limbo than move on to any romantic or sentimental plane.

The film has a tight structure, the first 40-odd minutes setting up the story and tracing Varner and Sarah’s journey to the ranch house, the next 20 minutes at the ranch alternating between comfort and discomfort as emotional release battles with restraint, the final 40 minutes the physical battle between the mostly unseen enemy and the farm occupants.

Stylistically, it is exceptional. The first section is all open vistas, characters minute figures on vast landscapes, the middle section suggests harmony with nature, and the final battle alternating between being the hunter and the hunted. When we first see Varner he is picked out along the edges of the screen as he leaps up or down or across rocky hillsides. That he appears and disappears at will could almost be the motif for the film.

Virtually everyone is in long shot or medium shot for the first half. Varner appears on the periphery of the screen and the action. He enters scenes where something important is being discussed, such as Sarah’s pleading to be allowed to leave the Army camp quickly. Most directors present Gregory Peck with aura intact, keeping him motionless on the screen to maintain his authority, but here he is always on the move, walking across open ground or confined spaces or darting across hillsides or through bushes, dashing on foot down slopes or racing on horseback.

Although the script – by Alvin Sargent (Gambit, 1966) and Wendell Mayes (Von Ryan’s Express, 1965) based on the T.V. Olson (Soldier Blue, 1970) novel – was viewed in many quarters as being underwritten, in particular Sarah’s role, and that there were too many silences for comfort, in the view of many that is the strength of the picture. There is none of the easy dialogue, crackling lines, coarse confrontation, sentiment or raw emotion of other westerns.

The movie hardly even skirts a cliché. This is in a class of its own in terms of the distance characters maintain between each other. Varner has very little to say, Sarah’s guilt restricts her vocabulary. In one regard the thriller element gets in the way of a study of two remote characters.

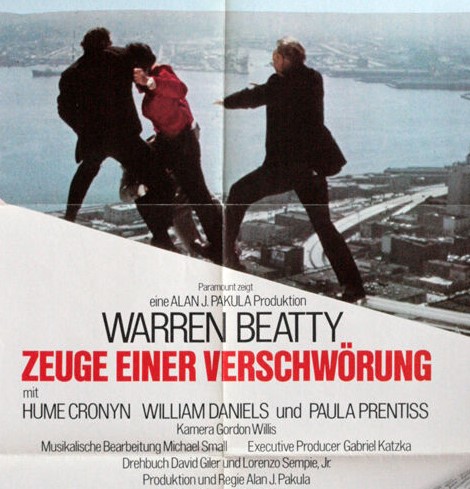

If I have any reservations about The Stalking Moon it is that is neither enough of a thriller nor enough of a character study. George Stevens might have sought emotional resolution and producer Alan J. Pakula, who later went on to direct Klute (1971) and The Parallax View (1974), might have proved more adept at marrying the thriller elements to personal anguish. Although The Stalking Moon may not have entered the pantheon of the greatest westerns, it is a very noble effort indeed, its slow pace and lack of dialogue providing it with a very modern appeal.