Hardly surprising Denholm Elliott comes a cropper in this delicious British upper class black comedy – he steals the show from denoted star Alan Bates. Had he kept going any longer you would hardly have noticed Bates even featured, such was the clever impact of Elliott’s insiduous playing.

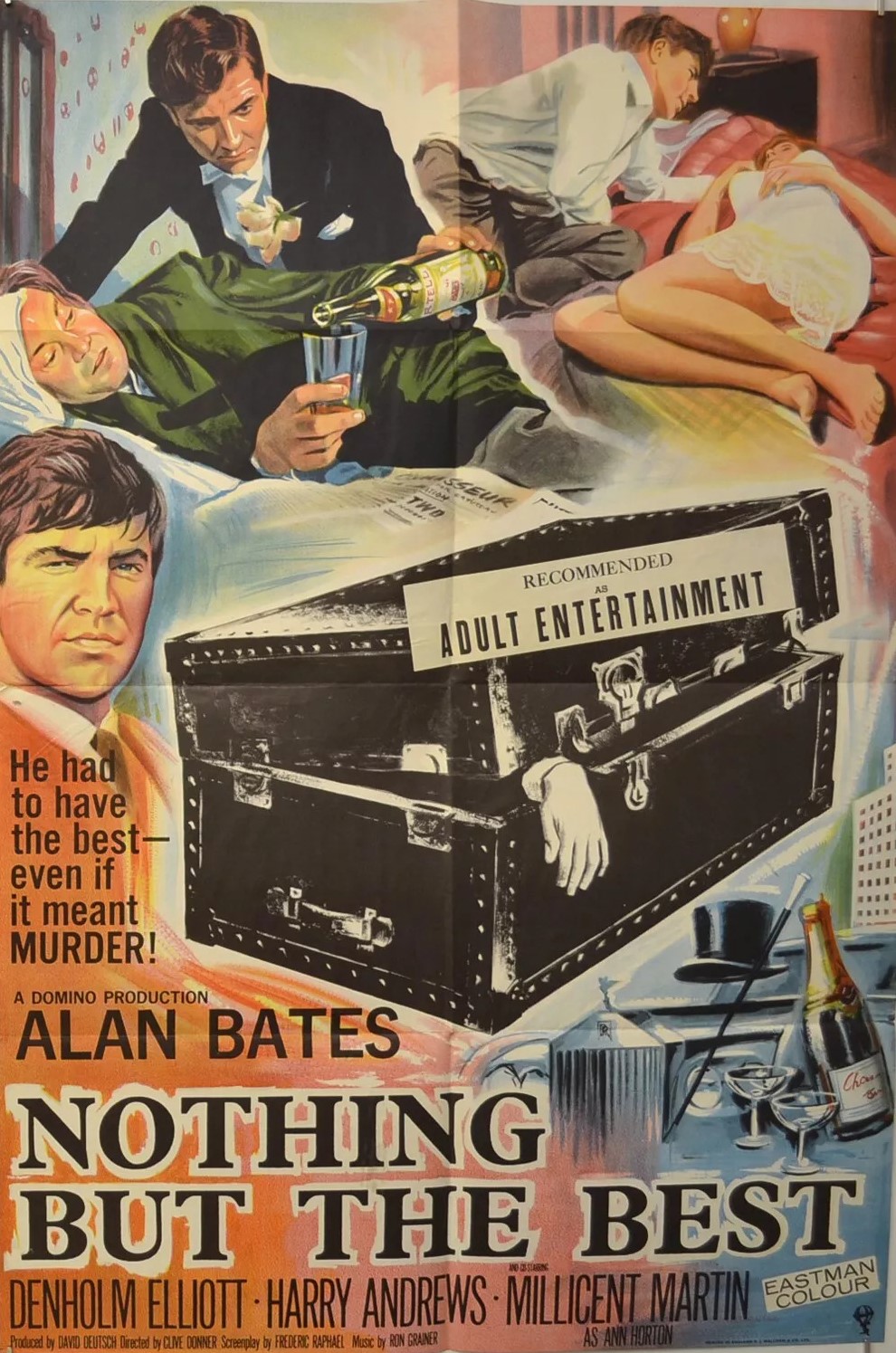

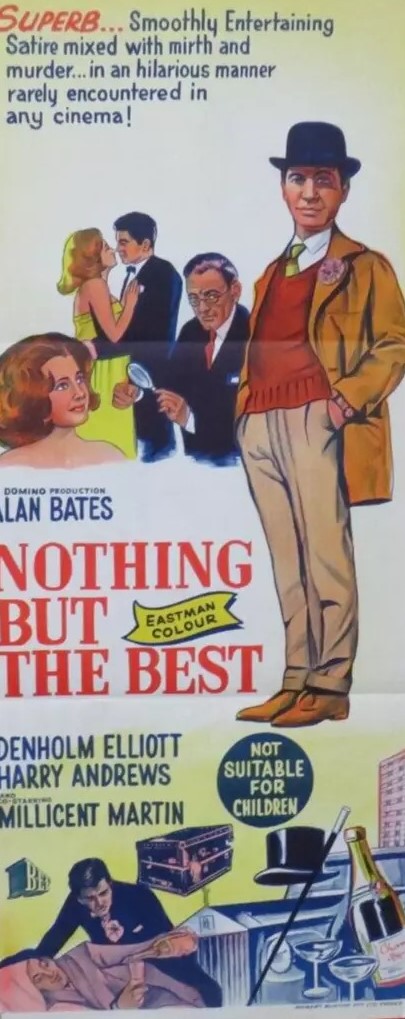

The toff version of Room at the Top (1958) meets Alfie (1966) as “ambitious young yob” Jimmy Brewster (Alan Bates) manipulates his way to the top. Too many people not coming up to scratch for his upwardly mobile purposes are cast aside – or strangled. Arrogance and bluff are the key to getting ahead in the upper-class world towards which he pivots. Doing absolutely nothing at all also works wonders in high society as does dismissing one’s hugely expensive education.

Jimmy is initially helped on his way, given an insider’s guide, by dissolute layabout toff Charles (Denholm Elliott) with a marked predilection for forgery, and other minor criminal schemes, but whose chief skill appears to be sponging off everyone else. Jimmy is a lowly executive in an upmarket estate agent, fighting for promotion against people with silver spoons rattling around every part of their anatomy and who have the genuine class their business appears to call for.

Every now and then the satire still contains contemporary bite, the difference between universities still relevant, as is that most people are not swayed by actual knowledge but by the fact that you can toss out the names of various academics. But, mostly, it’s bluff that opens the doors. Jimmy misses an appointment with an important banker, a dereliction that should have scuppered his chances of negotiating a better deal for his client. But, in fact, the banker takes this as Jimmy having gone elsewhere and immediately offers a better deal.

When confronted by a colleague for ignoring another appointment, Jimmy merely vaguely waffles on about being detained by “Sir Charles,” true identity left shrouded in mystery, contentious colleague silenced by either not being on speaking terms with the person mentioned or unwilling to admit his ignorance.

Having seduced every secretary within reach – none of whom meet his lofty standards – Jimmy manages to wangle his way into catching the eye of wealthy boss Horton (Harry Andrews) and his attractive daughter Ann (Millicent Martin), whom he marries.

While this would have been sharp as a tack in satirical terms back in the day, most of that weaponry is now out-dated. Suffers because none of the upper-class characters show any sense whatsoever – they can’t all be duffers and most seem to have tumbled out of central casting’s idea of an upper class twit. Charles is the exception, but even he is something of an innocent, not quite aware of what ruthlessness he has unwittingly set afire.

The lower classes aren’t much better. Secretaries and switchboard girls fall at Jimmy’s feet, handsome beggar that he is, though his landlady Mrs March (Pauline Delaney) appears to have his measure and is not above indulging in hypocrisy.

The voice-over works to the detriment of the picture. Because that device is doing so much of the heavy lifting, filling in the audience on Jimmy’s true feelings, the actor doesn’t have to do much acting and we’re presented with a kind of wooden figure who hides behind a mask. Of course since he’s masking his feelings, you might be inclined to give Alan Bates the benefit of the doubt.

And it would work very well if there wasn’t Denholm Elliott giving a master class in duplicity. He exhibits genuine charm.

I’m guessing that the voice-over was already there in Frederic Raphael’s script and not added to compensate for Alan Bates’s one-note performance. So if it was, that certainly presented a problem for the actor since most of what made his character interesting was at one remove, not presented in dialog or confrontation as would be the norm.

Alfie solved the problem by breaking the fourth wall – all the rage these days – and having the character directly address the audience, which allowed Michael Caine to present his own case.

So, if Alan Bates felt limited in what he could show on screen, he certainly does a good job of maintaining the façade. But Denholm Elliott (Station Six Sahara, 1963) steals the show. Harry Andrews (The Charge of the Light Brigade, 1968) is permitted no nuance to his normal bluff persona, singer Millicent Martin (Alfie, 1966) sparkles, and a bunch of British character actors including James Villiers (Some Girls Do, 1969) and Nigel Stock (The Lost Continent, 1968) put in an appearance.

Directed with some glee by Clive Donner (Alfred the Great, 1969) from a script by Frederic Raphael (Darling, 1965) adapted from a short story by Stanley Ellin (House of Cards, 1968).

Not as coruscating now as originally intended.