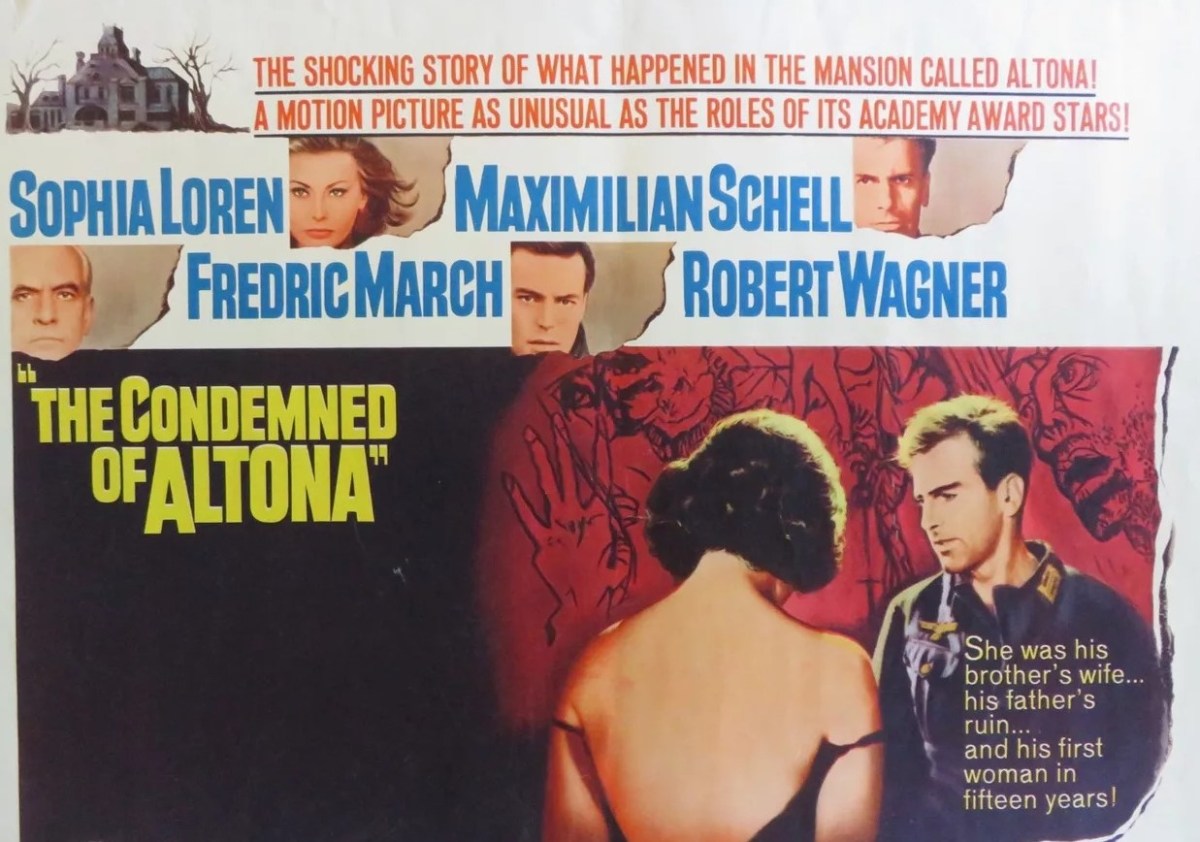

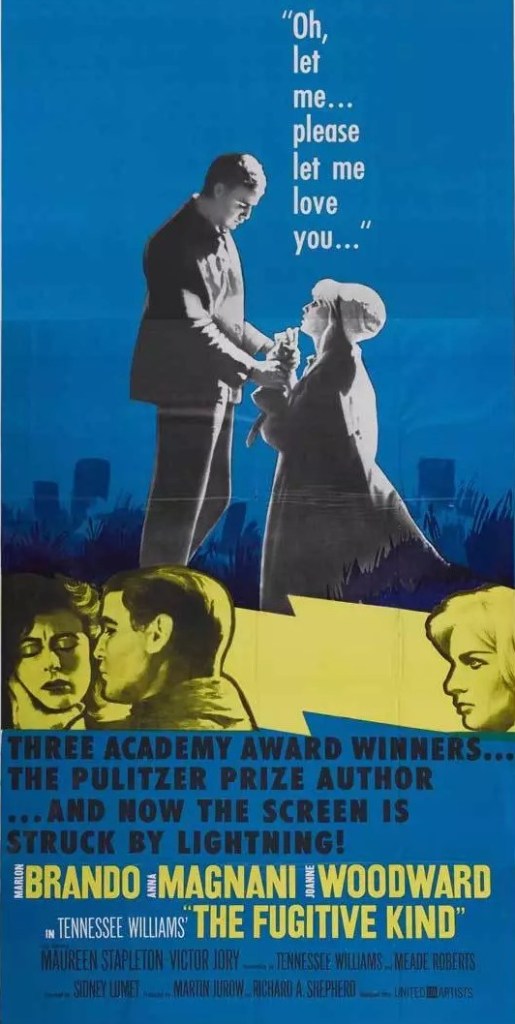

Audiences were promised sparks that never appeared. Marlon Brando (The Chase, 1960) remained electric but his charismatic screen presence wasn’t matched by miscast co-stars Anna Magnani (The Secret of Santa Vittoria, 1969) and Joanne Woodward (Paris Blues, 1961). That was three Oscars right there. Throw in a Pulitzer Prize for playwright Tennessee Williams and the project should have been home and dry.

Instead, it struggles to get going as the screenplay flounders under a flotilla of old maids, alcoholics, drug fiends, racists and deadbeats while the central conceit of a May-December romance fails to catch fire. That last element is something of a contemporary trope, and one that even now is exceptionally hard to pull off and it was no easier back in the day.

Itinerant guitarist and sometime criminal Valentine (Marlon Brando), desperate to go straight, ends up in a small Mississippi town when his car breaks down on a stormy night and he finds shelter in the home of Vee Talbot (Maureeen Stapleton), wife of the sheriff. Given his good looks, it’s likely that Valentine would be viewed as a catch, but in this small town he appears to have stumbled upon a nest of sexually frustrated and/or voracious women, way too many dependent on the kindness of a stranger.

First to throw her hat, and virtually everything else, into the ring is the young vivacious unfettered alcoholic Carol (Joanne Woodward), outcast of a wealthy family, barred from shops and bars alike for her uninhibited behavior. But Valentine’s seen too much of her kind. Next up is middle-aged dry goods shop owner Lady Torrance (Anna Magnani) who gives him a job as a counter hand. Bitter and frustrated, she has to run after morphine-addicted husband Jabe (Victor Jory). Vee hovers around trying to pick up the pieces.

Small town, jealousy rife, word bound to get back to duped husbands, tragedy the outcome. By this point the Deep South on screen was pretty much played out as are the various basket cases who inhabit it and there’s not much fresh ground to be ploughed here. Valentine is called upon to do “double duty” as employee and lover, and finally responds to her sense of desperation.

He can’t quite cut his ties to the illicit, stealing from the cash register to fund a gambling stake, and when caught is subtly blackmailed.

The backstory mostly concerns Lady. Her father’s wine plantation was destroyed by vigilantes in revenge for him selling liquor to African Americans. She wants to establish her independence by setting up a confectionary stall. Turns out of course it’s her husband that led the vigilantes. Valentine totes around a guitar that he never plays, as if it’s a reminder of a previous life. He’s running away from a past in New Orleans without any idea of the future to which he aspires. He doesn’t know what he wants but won’t make a move in case it’s the wrong one. He may desire a mother more than a lover.

It’s all set for a violent melodramatic ending, though the climax doesn’t ring true. Mostly, it’s about loneliness, both within and outside marriage. Relationships fester rather than last. The males are brutal or impotent.

While Joanne Woodward is determinedly over-the-top with her good-time-bad-girl routine, way out of control, and using over-acting as a crutch, Brando’s performance is more subtle and Magnani’s heart-wrenching.

But it just doesn’t add up. There’s too much emphasis on seedy background and forced drama. Williams has an alternative of the Raymond Chandler edict of when in doubt have a man come through a door with a gun; with him it’s unwanted pregnancy.

Director Sidney Lumet (The Appointment, 1969), who would later be more sure-footed, seems unsure here, the faux noir adding little, and inclined to indulge over-acting from the bulk of the supporting cast. Meade Roberts (Danger Route, 1967) adapted the Williams’ play.

An excellent Brando can make up for the rest.