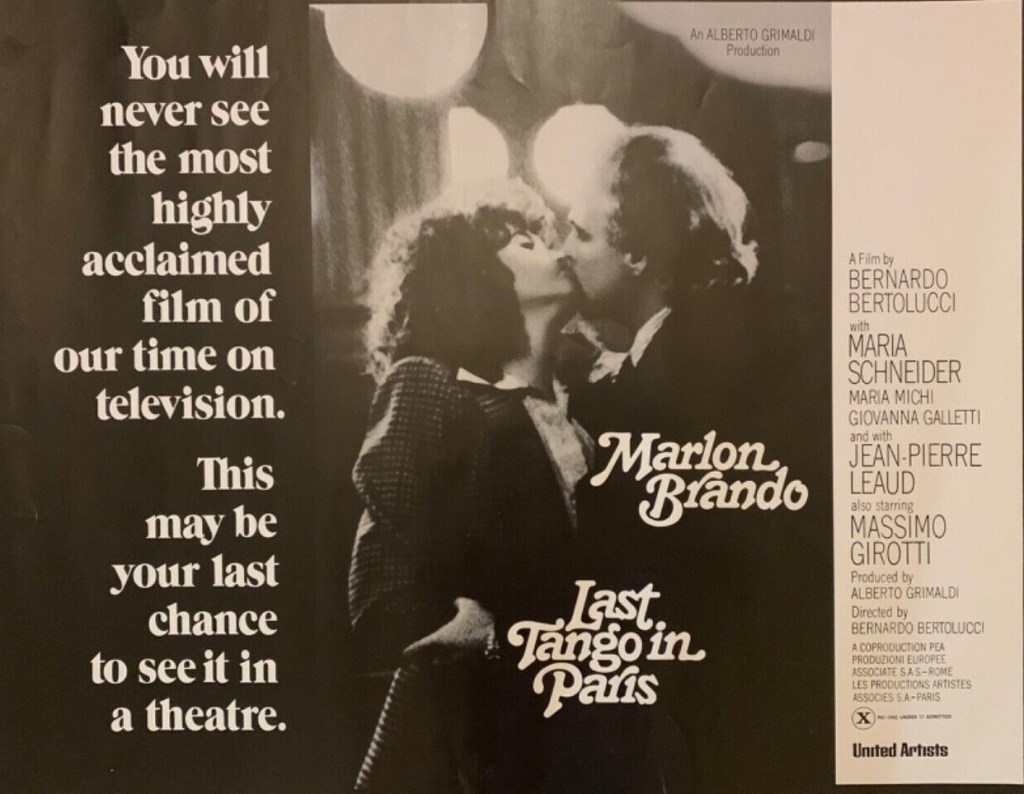

Yes, same cinema as The Great Race, since you’re asking, the Fine Arts in Los Angeles. American actors had been heading for Europe for over a decade seeking artistic redemption – Burt Lancaster in The Leopard (1963) – or commercial validation, Clint Eastwood in the “Dollars” trilogy and Charles Bronson in Adieu L’Ami (1968). But somehow Marlon Brando managed both at once after hooking up with Italian Bernardo Bertolucci (The Conformist, 1970) for an atypical look at the traditional French romance.

Not content with becoming the poster boy for the Mafia, and in passing (at the Oscars) highlighting the cause of the Native American, Marlon Brando helps push the soft porn envelope with what is now more properly viewed as a typical May-December love story featuring a somewhat predatory male and a young actress who now feels there is a case to answer in the Me Too department.

Setting aside the sexuality, there’s more than enough angst to go round. Paul (Marlon Brando) is mourning the death of his unfaithful wife who committed suicide while Jeanne (Maria Scheider) is in an unsatisfying relationship with a wannabe filmaker who seems unable to commit to genuine intimacy. Perhaps, she wasn’t expecting to get hot and heavy with the first older American male she comes across while searching for an apartment but the tang of sexual mystery proves irresistible. At first she’s happy to go along with the notion that they are an anonymous pair who meet only to couple, but, of course, soon enough she wants to know more about her lover than the tales he spins, some of which may be true.

She certainly was unprepared for anal rape, and whether the actress knew what was coming any more than Sharon Stone did in Basic Instinct (1992), you can’t help but feel a director has certainly taken advantage of a young actress probably too intimidated to complain.

When Jeanne comes over all whiny, the tale slips away into more cliched territory, even more so by the end when Paul has decided, too late, he needs to own up to his emotions, by which point she is slipping out of his grasp. A less authentic ending you couldn’t find, especially given the rawness of what has come before.

But there’s still a standout performance here, mostly because, without the need to be pinned down by the demands of narrative, Brando is given enormous leeway, and this may well stand as his most virtuoso piece. Sure, he immersed himself in the character of Don Corleone in The Godfather (1972) but this seems more real, a character, who in the act of witholding his emotions, spills them out with his eyes every few minutes. Paul is as full of charm, wheedling, playful, spouting nonsense, as he is calculating and demanding.

That he fails to blame himself for his wife looking elsewhere for affection or for any part he might have played in her death while cavorting with a more submissive lover seems to define him far better than any confessional monologue. For a closed-down shut-off kind of guy he certainly had plenty to say, and it’s the combinaiton of loquaciousness and taciturnity that brings him so much to life.

Maria Scheider (The Passenger, 1975) is the weak link here. Less than 20 years old when the film was made, her acting inexperience adds to her character’s innocence, but there’s no way she would ever, at that age, be able to hold a candle to Brando. So it’s an unequal pairing, as ultimately the fictional coupling proved to be.

There are tremendous flaws in the script, not least the drawn-out ending, and Jeanne’s boyfriend Tom (Jean Pierre Leaud) seems a tad too facile and almost a metaphor for Bertolucci himself, treating women with scorn, viewing them only through a lens, and that, darkly.

Hailed very much as groundbreaking cinema at the time, and dealing a death blow to the censorship system, this has lost much of that power but still remains in the top tier of Brando performances and coupled with The Godfather provided the actor with the commercial clout to bring Hollywood to heel as it had done in his glorious 1950s heyday.

Worth it for Brando’s performance but I doubt if you will come away feeling comfortable about the use of directorial power.