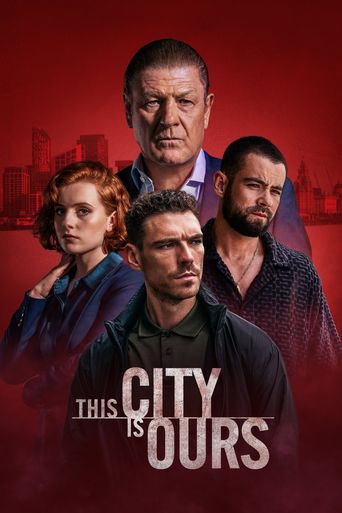

Knockout! Just stunning! I’m running out of superlatives for this one, the best crime series since The Wire (2002-2008). For sure, it takes a lead from The Godfather (1972) in that the core concerns family. But in a far more emotional manner than the Coppola epic where apart from a couple of scenes between Michael (Al Pacino) and his father (Marlon Brando) actual male expression of feelings is kept to an absolute minimum as though that might contaminate the pot.

Here, women, both in their relationships with husbands/fiancés, and their own naked ambition are very much to the fore. The new generation of males are vulnerable because of their desire for family, utterly exposed by love for babies and unborn babies, as opposed to old school boss Ronnie Phelan (Sean Bean) who spent little time with his son. And the fear of those on the fringes of being excluded from the “family” or those on the inside being cast out gives the narrative an iron soul.

The nail-biting climax is driven by three incidents involving the most vulnerable and therefore the most loved members of the clan. There’s betrayal, revenge and double-crossing but none of the infidelity or drug/alcohol abuse that was often a hallmark of the genre.

The tale pivots on three events. The first is of the brooding variety. Ronnie has allowed Michael Kavanagh (James Nelson-Joyce), almost an adopted son, to take the lead in crucial negotiations with Spanish drugs kingpin Ricardo (Daniel Cerqueira) much to the annoyance of his son Jamie (Jack McMullen). The second is that, in consequence, Jamie decides to hijack the next shipment. When Ronnie discovers his son is behind the plot, he decides not to follow up, and Michael realizes that blood is indeed thicker than water and that he will be squeezed out of his position in the organization. So he kills Ronnie and assumes command.

Except Jamie doesn’t take too kindly to this notion and, although generally not too bright and certainly way too impulsive for his own good (the Sonny, to keep The Godfather parallel going, of this particular gang), works out that only Michael had the motive to commit the murder which of course Michael strenuously denies. Both convince themselves the only way to take control is to rub the other out.

And then we’d be in standard gangster territory except for the other, emotionally-driven, plotlines. Jamie has a son he absolutely adores. Michael, with an unexpectedly low sperm count for a hardman, is hoping for an IVF baby with his girlfriend Hannah (Diana Onslow), a respectable businesswoman but hiding a very dark secret. Michael’s sidekick Banksy (Mike Noble) is grooming his son in the business. Ronnie’s wife Elaine (Julie Graham) treats Michael like a son and is inclined to take his side against Jamie. Rachel (Laura Aikman), wife of Jamie’s sidekick Bobby (Kevin Harvey), has ambitions way above her station of lowly book-keeper. She finds a way of finessing the fact that she physically controls the organization’s cash – and that it’s Ronnie’s wife whose name is on anything the gang owns – to exploit the divisions in the family as a means of of becoming the de facto “Godmother.”

Meanwhile, Ricardo, for good reason, distrusts Jamie and will only do deals with Michael, for whom he acts as mentor (so, if you like, Michael has two dads) although Jamie plans to sidestep the Spanish connection and go elsewhere for drugs which would have the dual effect of leaving Michael isolated and, with Rachel controlling the purse strings, potentially millions of pounds in debt. And hovering in the wings is a crafty cop, causing problems in every sneaky way possible, and a liability Cheryl (Saoirse Monica-Jackson), stuck with keeping to the code of omerta even though she guesses Ronnie wiped out her husband.

So it’s a game of shifting loyalties, grasping after power, with uber gangsters laid emotionally low by commitments to babies and pregnant wives. There’s none of the posturing of The Godfather, no making excuses for career choice or murderous thugs who draw the line at dealing drugs or women purportedly unaware of what their husbands do for a living.

Directed with occasional elan and pace and a great nose for the cliffhanger. Terrific writing by Stephen Butchard (The Last Kingdom, 2015-2018), both in dialog and twists on character interaction, and with a marvellous sense of narrative. You never know which way it’s going to go.

But most of all bursting with outstanding talent. You won’t see a deader eye this side of Clint Eastwood than James Nelson-Joyce (A Thousand Blows, 2024-2025) in his first leading role, who’s as comfortable exploring his own emotions as planning destruction. Mother hen Julie Graham (Ridley, 2022-2024) could easily turn into Ma Barker. Hannah Onslow (Belgravia: The Next Chapter, 2024) is tormented by her secret. Laura Aikman (Archie, 2023) manipulates and schemes. Virtually the entire cast are seasoned television actors, yet they’ll never have been lucky enough to encounter such character depth before.

Get on to your local streamer/television station and harangue them to buy this from the BBC.

As I said I’ve run out of superlatives.