Just like the All-Time Top 40, this is based on views on the Blog. I realized I didn’t do a catch-up last year and haven’t done one in two years so it kind of feels redundant to do a previous-year’s-position in brackets number.

All of these movies incurred problems – budget, changes of director or star, censorship issues, studio indifference – and for some it’s a surprise they ever made it onto the big screen.

- Waterloo (1970). Sergei Bondarchuk’s roadshow epic with Rod Steiger and Christopher Plummer.

- The Satan Bug (1965). John Sturges adaptation of Alistair MacLean pandemic thriller, striking a stronger note now than when originally release.

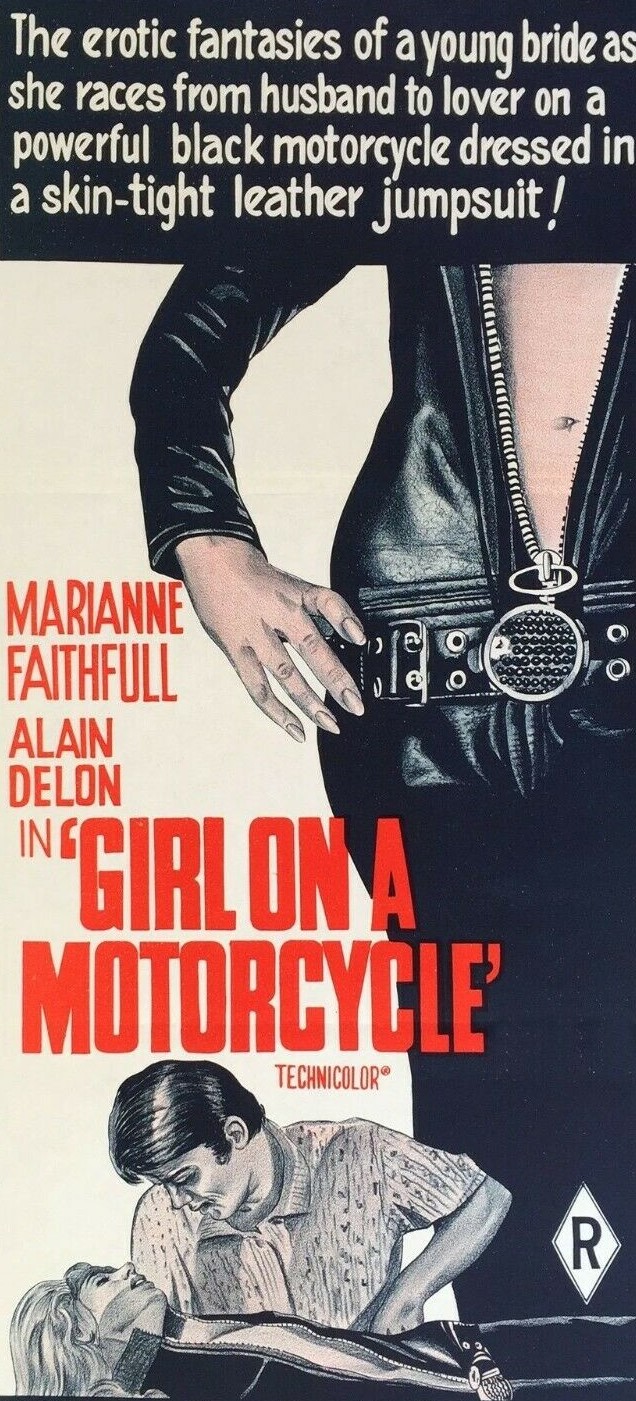

- The Girl on a Motorcycle / Naked Under Leather (1968). Marianne Faithful in leathers, what more can you say, except the U.S. censors took umbrage and cut out most of what Europe went crazy for.

- Ice Station Zebra (1968). John Sturges again. Alistair MacLean again. Big budget roadshow set mostly under the polar ice cap.

- The Guns of Navarone (1961). All-star cast for J. Lee Thompson WW2 epic.

- Cast a Giant Shadow (1966). Comedy director Melville Shavelson goes straight with Israeli action picture starring Kirk Douglas, Frank Sinatra, John Wayne and Senta Berger.

- In Harm’s Way (1965). John Wayne and Kirk Douglas (again) in Otto Preminger’s examination of Army politics pre- and post-Pearl Harbor.

- Spartacus (1961). Battle between the Kirk Douglas vehicle and a rival production from Yul Brynner.

- Battle of the Bulge (1965). Cinerama to the fore in the battle of the tanks in WW2.

- The Cincinnati Kid (1965). Sam Peckinpah fired, Norman Jewison takes over, Steve McQueen perfects his iconic loner in poker drama.

- Secret Ceremony (1969). Elizabeth Taylor, Mia Farrow and a creepy Robert Mitchum in odd Joseph Losey drama.

- The Ipcress File (1965). The spy picture that attempted to upend the Bond applecart. Michael Caine’s most iconic role.

- Genghis Khan (1965). Though way down the credits, Omar Sharif in the title role.

- Sink the Bismarck! (1962). British war film starring Kenneth More that does what it says on the tin.

- They Shoot Horses, Don’t They (1969). Decades in the making, finally surfacing with a dream cast of Jane Fonda, Michael Sarrazin and Susannah York.

- Doctor Zhivago (1965). Selling the David Lean epic.

- The Shoes of the Fisherman (1968). Whoever imagined this would work as a roadshow? Anthony Quinn headlines.

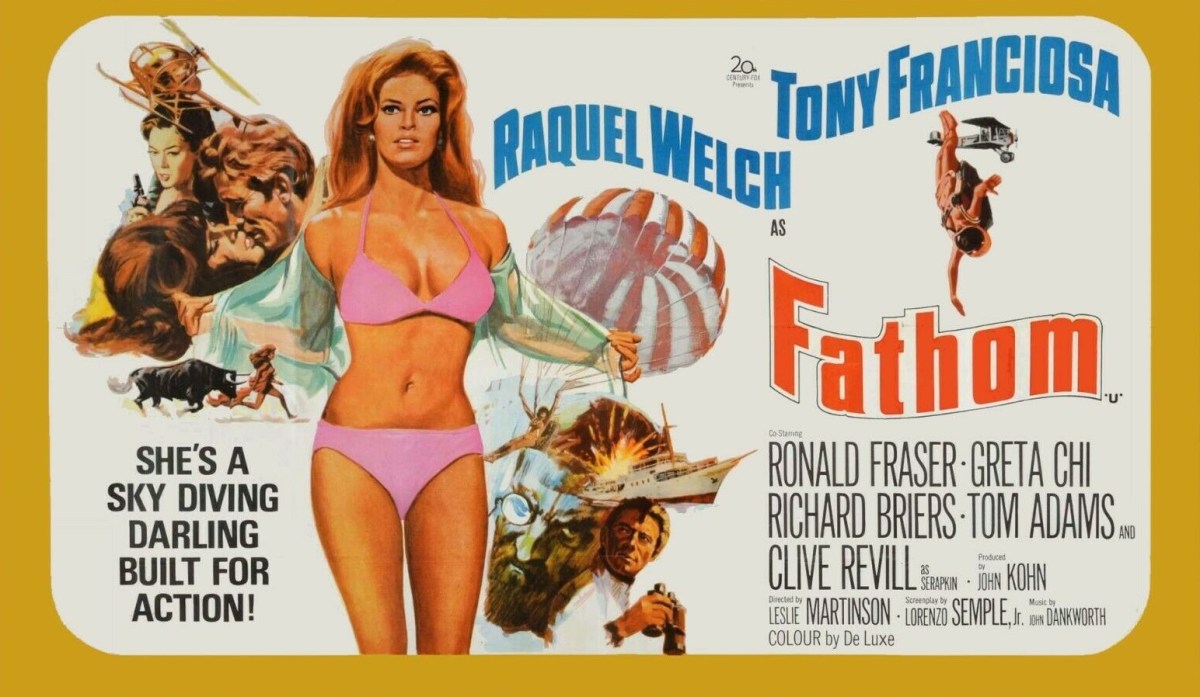

- The Biggest Bundle of Them All (1968). Raquel Welch effortlessly steals the show in Italian caper.

- Night of the Living Dead (1968). Horror was never the same after George A. Romero went to work on zombies.

- The Way West (1967). Underrated Andrew V. McLaglen western with top-notch cast in Kirk Douglas, Robert Mitchum and Richard Widmark.

- Valley of the Dolls (1967). Would have been Judy Garland’s last hurrah except she was fired.

- When Alistair MacLean Quit: Part Two. Not content with serving up concepts that were turned into some of the best films of the decade, the bestselling author had his own demons to battle.

- The Wicker Man (1973). The trap is sprung on naïve Scottish cop in movie that was flop on release but is now considered one of the best horror films ever made.

- The Secret Ways (1961). Richard Widmark hunted in Hungary in adaptation of Alistair MacLean thriller. The star finished off the picture when Phil Karlson quit/was fired.

- Humphrey Bogart: 1960s Revival Champ. The reason Bogart became so iconic for a new generation: his reissued movies proved box office dynamite.

- Once Upon a Time in the West (1969). The inside story of the Sergio Leone classic.

- 100 Rifles (1969). Raquel Welch, need I say more…well, yes, because Jim Brown brings a helluva lot to the action.

- The Bridge at Remagen (1969). Producer David Wolper didn’t count on Russia invading Czechoslovakia when he scheduled his shoot.

- The Man in the Middle / The Winston Affair (1964). Robert Mitchum defends an apparently guilty man.

- When Box Office Went Worldwide. In the 1960s nobody reported foreign box office so you had to dig deep like I did to find the information all hidden away. Fascinating reading especially as it shows what films touted as successes were actually flops.