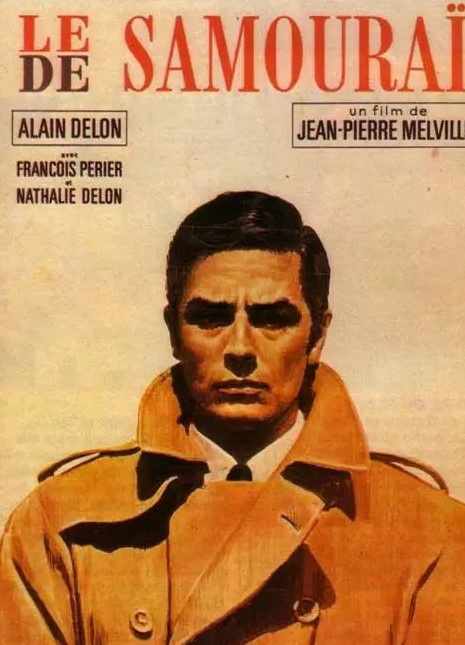

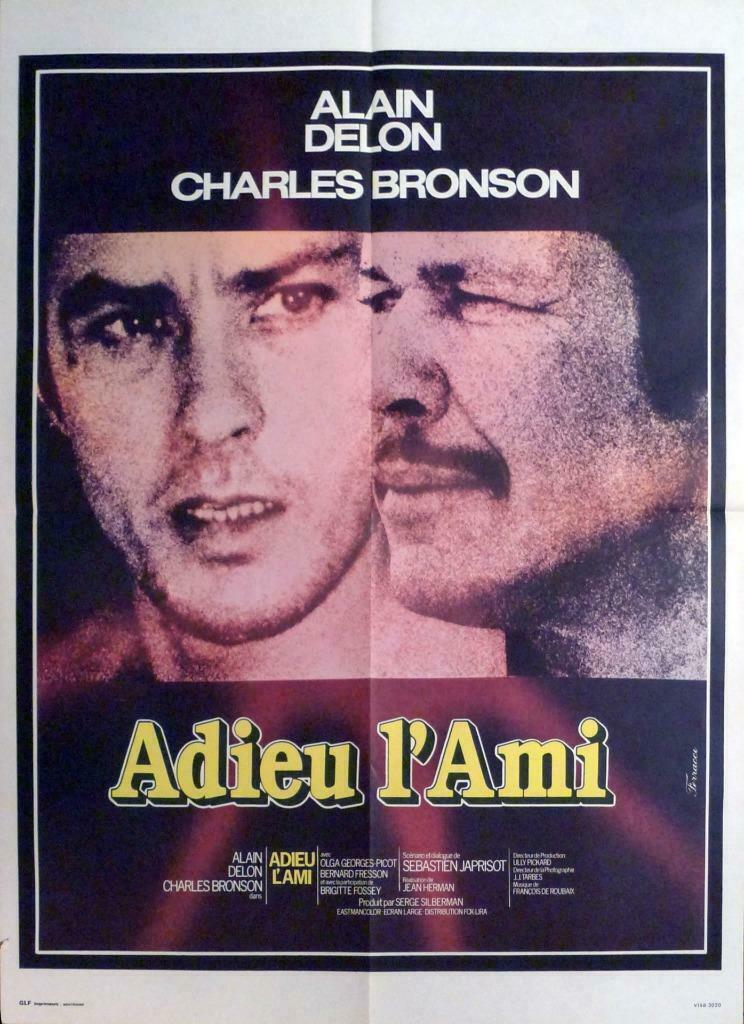

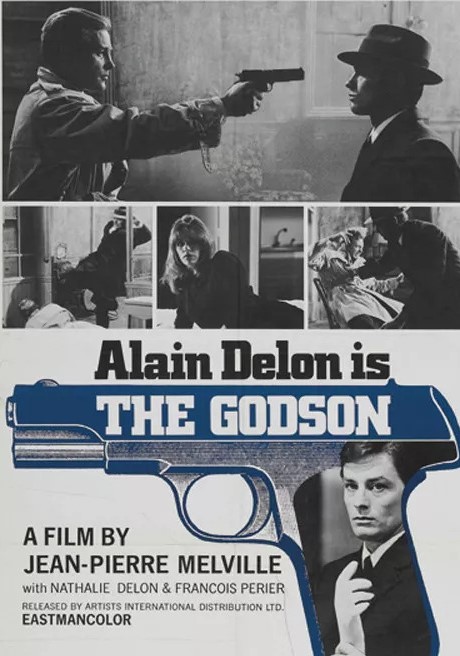

The current trope for giving assassins nicknames – viz Day of the Jackal (2024) – doesn’t stem from Jean-Pierre Melville’s spare picture, the title here more suggestive of the idea of killing as an honorable profession. One of the most influential crime movies of all time, it resonates through Michael Winner’s The Mechanic (1972) – though few critics would give that the time of day -Walter Hill’s The Driver (1978), John Woo’s The Killer (1989), Anton Corbijn’s The American (2010), Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive (2011) and David Fincher’s The Killer (2023). Even so, few acolytes can match the opening scene of a room empty except for a whiff of smoke in a corner that indicates the presence of recumbent killer Jef (Alain Delon).

There’s none of the false identity malarkey of Day of the Jackal and no high-echelon ultra-secret secret service figures involved in tracking him down. In fact, one of the delights of the movie is the police procedural aspect, with the top cop, here known only as the Commissaire (Francois Perier), insisting on dragging in at least 20 “usual suspects” from each district. Though living a Spartan existence, Jef at least has the sense to acquire an alibi from the lover Jane (Nathalie) he shares with a wealthier man. Nor is he killing public figures. Instead, more like someone from Murder Inc., rubbing out other gangsters.

The witnesses provide conflicting information on the man they saw, but the Commissaire does not entirely trust Jef’s alibi, putting pressure on Jane to recant. Her paying lover Weiner (Michel Boisrond) provides a pretty accurate description of Jef. While the cops bug his apartment and start to shadow him, Jef falls foul of his anonymous employer who is alarmed at the attention the assassin has attracted and to avoid the possibility of being implicated sets an assassin onto the assassin.

Wounded, refusing to accede to Jane’s demand that he acknowledge he “needs” her, he tracks down the assassin’s boss, Oliver Rey (Jean-Pierre Posier), who happens to be the lover of Valerie, a nighgclub singer Jef takes a shine to. It’s worth noting that there’s an innocence – or perhaps an honor matching that of the samurai – in the police behavior. The Commissaire exists in a world where rules are not bent or broken, where suspects are not beaten up, and where often the cops are hamstrung by procedure and must take special care in arriving at a conclusion. To convince himself that Jef is indeed the correct suspect, the Commissaire makes him swap hat and coat with others in a line-up, only for the witness to identify the coat, hat and face that he believes he saw. It’s only Jane’s unbreakable alibi that keeps Jef safe.

Most of the picture is pure bleak style. You never enter the assassin’s head. There’s no background or backstory to shed any light on action. Even the most appealing characters, Jane and Valerie, occupy moral twilight. I’m not sure Melville’s in a mood for homage, though Robert Aldrich was in the Cahiers du Cinema hall of fame, but the ending comes close to replicating that of Aldrich’s The Last Sunset (1961), not just for the climactic action but for the inherent self-realization of unavoidable consequence.

Despite sparseness of the style, there’s enough going on emotionally and action-wise to keep an audience enthralled. While his outfit echoes the Humphrey Bogart private eye of the 1940s, and while walking the same mean streets, Jef is the antithesis of that untarnished hero.

Melville belonged to the hard-boiled school of cinematic crime, summoning up the gods of noir, and providing a new breed of French star with tough guys to kill for. He died young, just 55, and left behind 14 pictures, at least three or four considered masterpieces including Army of Shadows (1969) and The Red Circle (1970). You might have thought his minimalist style would appeal more to critics than moviegoers but in his native France, in part because stars queued up to be in his movies, he was highly popular.

When you compare the Delon of this to Once a Thief (1965) or Texas Across the River (1966) you can see how much acting goes into the restraint of the character here, producing one of Delon’s best performances. His wife of the time, Nathalie Delon (The Sisters, 1969) shines but briefly.

Recommended.