You ever wonder what William Peter Blatty got up to before he scared the bejasus out of everyone with The Exorcist (1973)? He was a screenwriter, churning out somewhat formulaic comedies like this. There were two approaches to this subgenre. The potential lovers hate each other on sight and spend the rest of the film annoying each other before they discover they are actually in love. Or, they are kept apart by the simple process of one of them being in love with someone else.

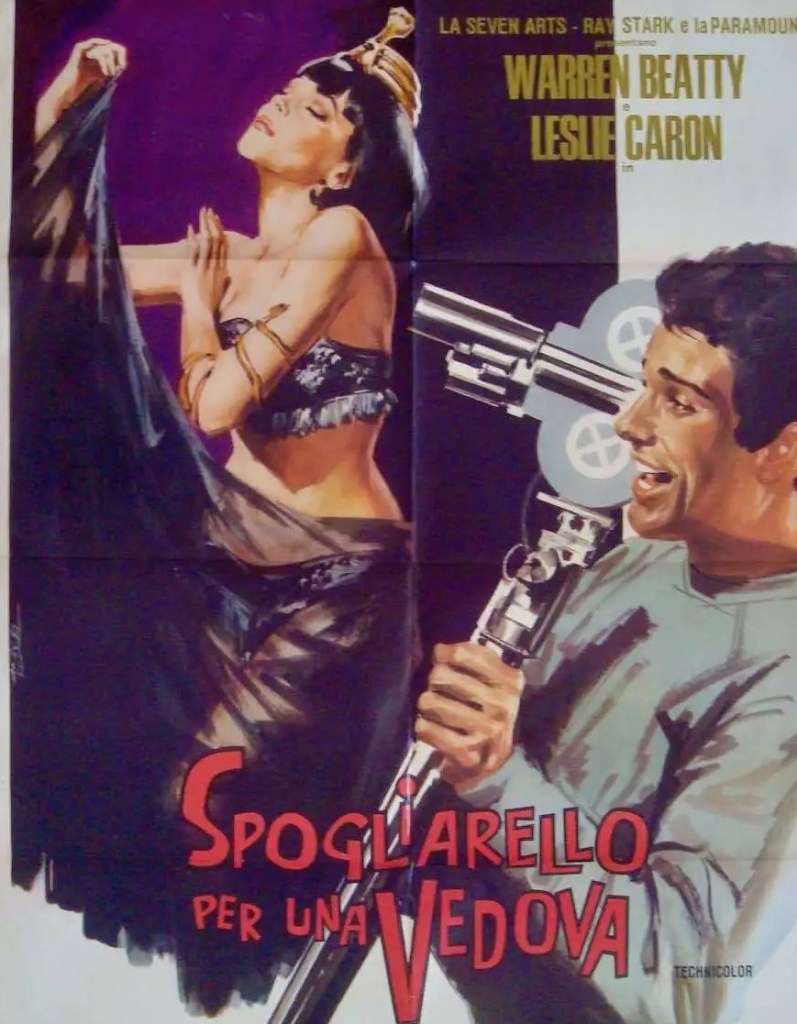

Here Michele (Leslie Caron), widowed single mother, is trying to get her hooks into boss Dr Brock (Robert Cummings), a child expert, because she thinks he would make a great father. So, largely, she ignores the seduction attempts of nudie film director Harley (Warren Beatty). What Michele doesn’t know is that Dr Brock hates children – though some of his concepts (mocked at the time) seemed quite prophetic such as “corporal punishment is an admission of failure by the parents.” But, basically, she offloads the kid onto neighbors, keeping him out of the way till she gets her man.

Meanwhile, her cute baby John Thomas (Michael Bradley) is doing all the work of bringing the couple together. He more or less adopts Harley as a surrogate father and filming him turns out to be the refreshing new idea the director needs to satisfy irate backer Angelo (Keenan Wynn).

This could as easily have been entitled Babies Behaving Badly for John Thomas is introduced to the audience escaping from his mother and wrecking a jewellery story and spends most of the picture getting into trouble, for which his cuteness provides the requisite get-out-of-jail-free card. (The child’s name probably was the only thing guaranteed to raise a chortle among British audiences).

You spend a lot of time waiting for Michele and Harley to get it together, during which time neither of the alternative narratives – the Michele-Dr Brock subplot and the filming of the child – offer much in the way of sustenance. Theoretically, Harley isn’t the standard seducer of the period, the well-off kind who lives in a cool or plush pad and does something financially or artistically rewarding for a living. He lives in a crummy apartment in Greenwich Village and struggles to make ends meet, blue movies not as remunerative as you might expect.

Michele’s character is stuck in the 1950s more than the more liberated 1960s, with the ideas that a child needs a father, that you should marry for security, and that there’s nothing wrong with snaring a man by devious means. She’s pretty uptight and old school.

Warren Beatty’s career was on a distinctly shaky peg. Since his breakthrough in Splendor in the Grass (1961) he had been bereft of a commercial hit and not found critical acclaim, though there were some takers for Arthur Penn’s Mickey One (1965). Like other actors had before him, he had fled to Europe in the hope of finding better opportunities, but all he managed was this (though set in New York it was filmed at Shepperton Studios in Britian) and heist picture Kaleidoscope the following year, neither of which solved his marquee issues.

Leslie Caron hadn’t quite found her niche either. Nothing she had done had topped Gigi (1958) and though Father Goose (1964) had been a commercial success it put her in the comedy category whereas her more interesting work of the decade had been in the drama genre – Guns of Darkness (1962) and The L-Shaped Room (1962). In fact, as a Hollywood leading lady, this was pretty much her swansong.

Robert Cummings (Five Golden Dragons, 1967) is good value and the cast includes Keenan Wynn (Point Blank, 1967), Hermione Gingold (The Naked Edge, 1961), Lionel Stander (Once Upon a Time in the West, 1969), British television actor Warren Mitchell (The Assassination Bureau, 1969), Margaret Nolan (Goldfinger, 1964) , Viviane Ventura (Battle Beneath the Earth, 1967) and a blink-and-you-miss-it role for Donald Sutherland (Riot, 1969). Directed by Arthur Hiller (Penelope, 1966).

Tame stuff.