Something of a cult in the peplum vein, Hercules (Reg Park), wanting to enjoy domestic life with his wife and son, is instead drugged by Androcles, King of Thebes (Ettore Manni) and spirited away by ship to Atlantis whose Queen Antinea (Fay Spain) is intent on global domination and the resurrection of the dethroned god Uranus to his rightful place in the heavens.

This isn’t your normal Hercules, either, not that keen on demonstrating his strength, preferring to sleep or lie around. It’s not your normal ship either, Androcles, unable to persuade his senate to properly fund the expedition, has crewed his ship with renegades who are inclined to abandon Hercules on the nearest island And unbeknownst to Hercules, his son has come along for the ride.

Of course, nothing goes according to plan and Hercules is soon shipwrecked on an island where he finds Ismene (Laura Efrikian) imprisoned on a rock as a sacrifice to the gods. Rescue never being simple, Hercules has to first withstand fire then tackle in quick succession snake, lion, eagle and a giant lizard. Ismene turns out to be Antinea’s daughter and the Queen, rather than being delighted at her return, is appalled for, according to the way the ancient world works with all its prophecies and religious ritual, the girl must be sacrificed to prevent the destruction of Atlantis.

Nor is Atlantis your usual kingdom. Even setting aside the peculiarities that mark the Greek world, this is a place where abnormality rules. Hercules finds Androcles, whom he believed died in the shipwreck, but it turns out to be a vision, or some kind of shape-shifting being. The Queen believes she can subjugate nature and has a tendency to throw those who disappoint her into an acid bath. There is a fiery rock that controls life and death.

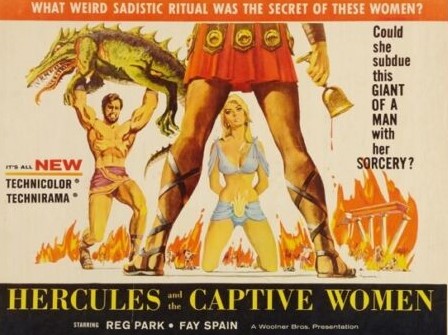

Like most of the peplum output, you have to accept a standard of production lower than the Hollywood norm, and the terrifying beasts sent to test the hero are not at all convincing, but on the plus side are feats of imagination that mainstream American studios would never conjure up, unless it was something that fitted into the swashbuckling genre. You pretty much have to go with the flow and accept what is offered in terms of narrative oddity. Bear in mind, too, that there is no one dressed in as skimpy a costume as suggested by the poster.

You also need to be get hold of a good copy. Several versions are available, some for free, where the colors are so washed out you can hardly determine what is going on never mind enjoy the costumes, creatures and sets as intended. This was filmed in Technirama 70, shot in 35mm but blown up to70mm widescreen for exhibition, so should generally be of a high technical standard – this was the process used by Spartacus (1960).

It’s not a film to fit into the so-bad-it’s-good category, but of course imagination too often exceeds budget which renders the filmmaking somewhat random at times and like the bulk of the peplums acting skill is not at a premium. As you might expect, the British-born Reg Park was a bodybuilder first – three times winner of the Mr Universe title – and an actor second. He played Hercules again another three times and Maciste once but outside this narrow comfort zone made no other films. But he was Arnold Schwarzenegger’s inspiration, so that was probably enough. American Fay Spain (The Private Life of Adam and Eve, 1960) never got beyond bit parts as a B-movie bad girl and television, although she was seen in The Godfather: Part II (1974). Italian Laura Efrikina made her debut here and cou would later spot her as Dora in the Italian television mini-series David Copperfield (1966).

Director Vittorio Cottafavi was steeped in peplum, from The Warrior and the Slave Girl (1958) to Amazons of Rome (1961) but although he worked consistently in television made only one other picture, 100 Horsemen (1964).