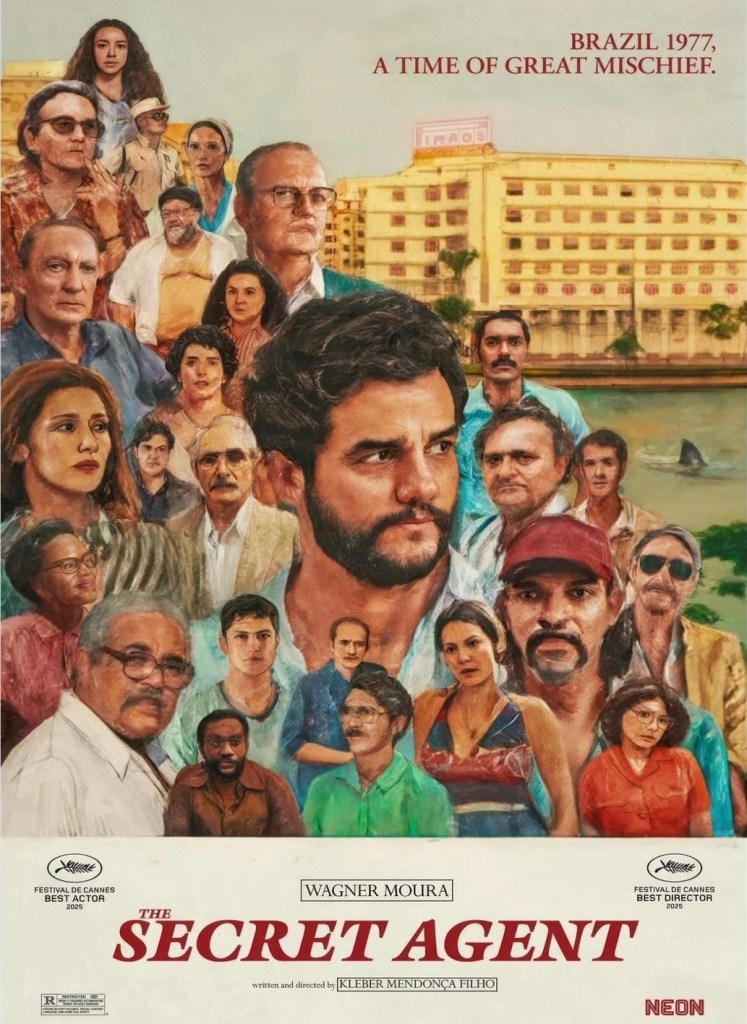

Now that publicists have hijacked film festivals in an effort to sell the public an unending stream of over-praised self-indulgent rubbish, it’s refreshing to come across a foreign film that is innovative, interesting and not over-acted. This meshes a thriller-like quality with the kind of surreal diversions that used to indicate movies not following the Hollywood dictat.

And while the storyline concentrates on brutal regimes and people persecuted for no reason except the authorities can get away with it, the potentially somber tone is undercut by homages to La Dolce Vita (1960) and Cinema Paradiso (1988). With time jumps, the movie takes its sweet time coming to a conclusion and when it does so, there’s an unexpectedly emotional twist.

It’s set in Brazil in 1977, but I have to confess I know little about the politics of the period except, judging by what goes on here, corruption is rife and justice is compromised. We begin with our hero, college professor Marcelo (Wagner Mauro) being shaken down at a petrol station by a pair of cops, who eventually are happy with just a packet of cigarettes as their booty. The cops pointedly ignore the corpse rotting in the sunshine.

The widowed Marcelo, on the run and using a pseudonym, is driving to Recife to reunite with his son who is living with his grandfather. Marcelo hides out in a house full of refugees, who are equally in danger. Marcelo has fallen foul, it eventually transpires, of an industrialist who wants to steal his research. Said businessman has despatched two hitmen to deal with this “transgressor” and the hitmen in turn hire a cheaper hit man to carry out the deed.

The surreality emerges when a human leg found in the belly of a shark attracts greater headlines than normal because the country is in the grip of Jaws-fever. The leg takes on a life of its own when it’s stolen from the mortuary and used to terrorize gay men making out in a public park. Attitudes to death are equally morbid, the cops taking bets on how high the death toll will run at the annual carnival.

The grandfather is a projectionist in the local cinema so we are treated to mentions of Jaws (1975), The Omen (1976) and King Kong (1976). Marcelo makes contact with the resistance who are trying to help him get out of the country. But he’s also landed a job in an ID unit where, on the side, he can hunt for information about his mother.

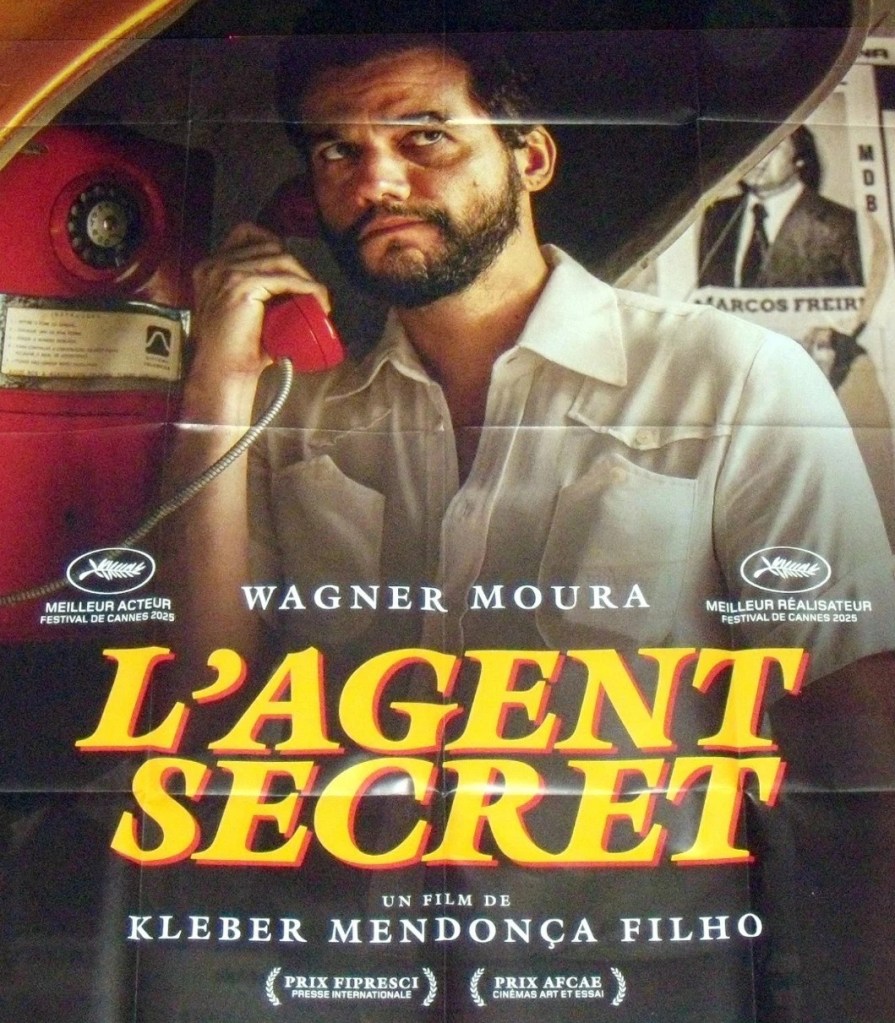

The title is ironic. There’s nothing dangerous about Marcelo and he doesn’t have secrets that can topple a regime, nor is he spying for a foreign power. But he does have to behave like a secret agent just to survive, dodging about, hiding in plain sight, making contact via codes and signals.

You are led to believe also that his every word is being taped and that there are collaborators only too ready to hand him over. But in fact, the story jumps around to the present day and a student doing research on the period.

Marcelo isn’t much of a hero in the normal Hollywood manner. He might be something of a lothario in the James Bond manner but he’s just trying to survive and get on better terms with his young son. His father-in-law, with some justification it appears, accuses Marcelo of hypocrisy – he’s grieving for a wife to whom he was serially unfaithful.

And it’s very honest on the emotional scale. Marcelo discovers that his mother, who was little more than a slave, was impregnated by a landowner when she was 14. When the present-day student confronts Marcelo’s grown-up child with information about his “heroic” father, hounded by a brutal regime, the son doesn’t want to know – he was brought up by his grandfather and that’s more important than a man he rarely saw and to whom he has little emotional connection.

So on the one hand it’s the kind of political thriller that many critics have viewed as holding up a light on brutal regimes around the world, but it’s not that kind of political thriller. It’s at its best when exploring ordinary life, and the way that ordinary people are treated by bad actors.

Wagner Moura (Civil War, 2024) is deservedly up for an Oscar but the movie is people with highly believable characters. Writer-director Kleber Mendonca Filho (Pictures of Ghosts, 2023) makes no sweeping political points but by concentrating on the small scale he more than compensates.

Thoughtful and enjoyable.