A dislocated, fractured film about disjointed, fractured people. Takes a heck of a long time to work what’s going on because director Richard Lester in the elliptical style of the times tells us bits of the story a bit at a time and no guarantee anything is in logical order or that the characters tell the truth about themselves or their actions. And, unusually, outside of a western, all the men appear prone to violence.

Petulia (Julie Christie), a self-appointed “kookie” (in the vernacular of the times) and married for just six months to wealthy naval architect David (Richard Chamberlain), for no reason at all begins an affair with surgeon Archie (George C. Scott) that she encounters at a posh function. Archie, getting divorced for no reason at all except boredom from Polo (Shirley Knight), already has a girlfriend, all-round-sensible boutique-owner May (Pippa Scott). Petulia and Archie may or may not have consummated the affair, she certainly puts him off often enough. Petulia may or may not be the daughter and sister of prostitutes. You see where this is going? Unreliable narrator, par excellence.

A broken rib may be the result of stealing a tuba from a shop. She could have cracked her head open after a dizzy spell. A Mexican boy keeps turning up and, it has to be said, nuns. It’s all very avant-garde: an automated hotel where the key comes out of slot and the fob sets off flashing lights at the bedroom door, the televisions in hospital rooms are dummies, Janis Joplin is the singer in a band, characters viewed in longshot down corridors, up car park ramps, emerging from tunnels.

Eventually the demented jigsaw puzzle comes together but not after a tsunami of overlapping dialog, flash scenes and snippets that have nothing to do with the film. It’s San Francisco so there’s a scene in Alcatraz. But little is constant, every marriage seems on the verge of break-up, even the contented Wilma (Kathleen Weddoes), wife of another surgeon, wishes she had Archie’s courage in ending his marriage.

But Petulia is anything but free-spirited. She is trapped and doesn’t know how to get what she wants. She may be a tad unconventional and big-hearted and occasionally small-minded but once you get to the end of the film and find what she really wants the rest of her behavior makes sense. And although Archie is able to verbalize what he doesn’t want from marriage, the only option open to Petulia is one apparently mad action after another.

Although set in the Swinging Sixties, the male hierarchical system remains dominant. Archie’s ex-wife relies on him for money, David and his father (Joseph Cotten) hold sway over Petulia regardless of her bids for freedom. David is unsavory, his father is willing to provide a false alibi, another surgeon Barney (Arthur Hill) lets loose with a vicious rant and even the harmless soft spoken Archie lets loose on Polo.

Julie Christie (Doctor Zhivago, 1965) makes Petulia as irritating as she is endearing, the freedom she expects to embrace in the counterculture impossible to grasp, leaving her only with the vulnerability of the vanquished. George C. Scott (The Hustler, 1961) has forsaken his growling persona, the volcanic screen presence set to one side, to portray a more interesting character, bemused by Petulia but ultimately standing up for her.

There’s an excellent supporting cast in Richard Chamberlain, still in the process of shucking off Dr Kildare (1961-1966), Arthur Hill (Moment to Moment, 1966), Shirley Knight (Flight from Ashiya, 1964) and Joseph Cotten (The Third Man, 1949).

Britisher Richard Lester (A Hard Day’s Night) was a director du jour who, while fulfilling the expectation of delivering cutting-edge techniques and casting a wry eye on contemporary mores, offered some surprisingly more homely family scenes and for a movie which is so much about the distance between characters many scenes of just touching, Petulia stroking Archie’s hands, Archie stroking is wife’s neck, even when the intimacy they seek is a forlorn hope. The incident with the tuba which would be a meet-cute to end all meet-cutes in other pictures turns into a cumbersome irrelevance. You get the impression that the chopping up of the time frames and the points of view reflects the characters’ feelings that they can impose their own reality on a situation. Lawrence B. Marcus (Justine, 1969) wrote the screenplay from the novel Me and the Arch Kook Petulia by John Hasse.

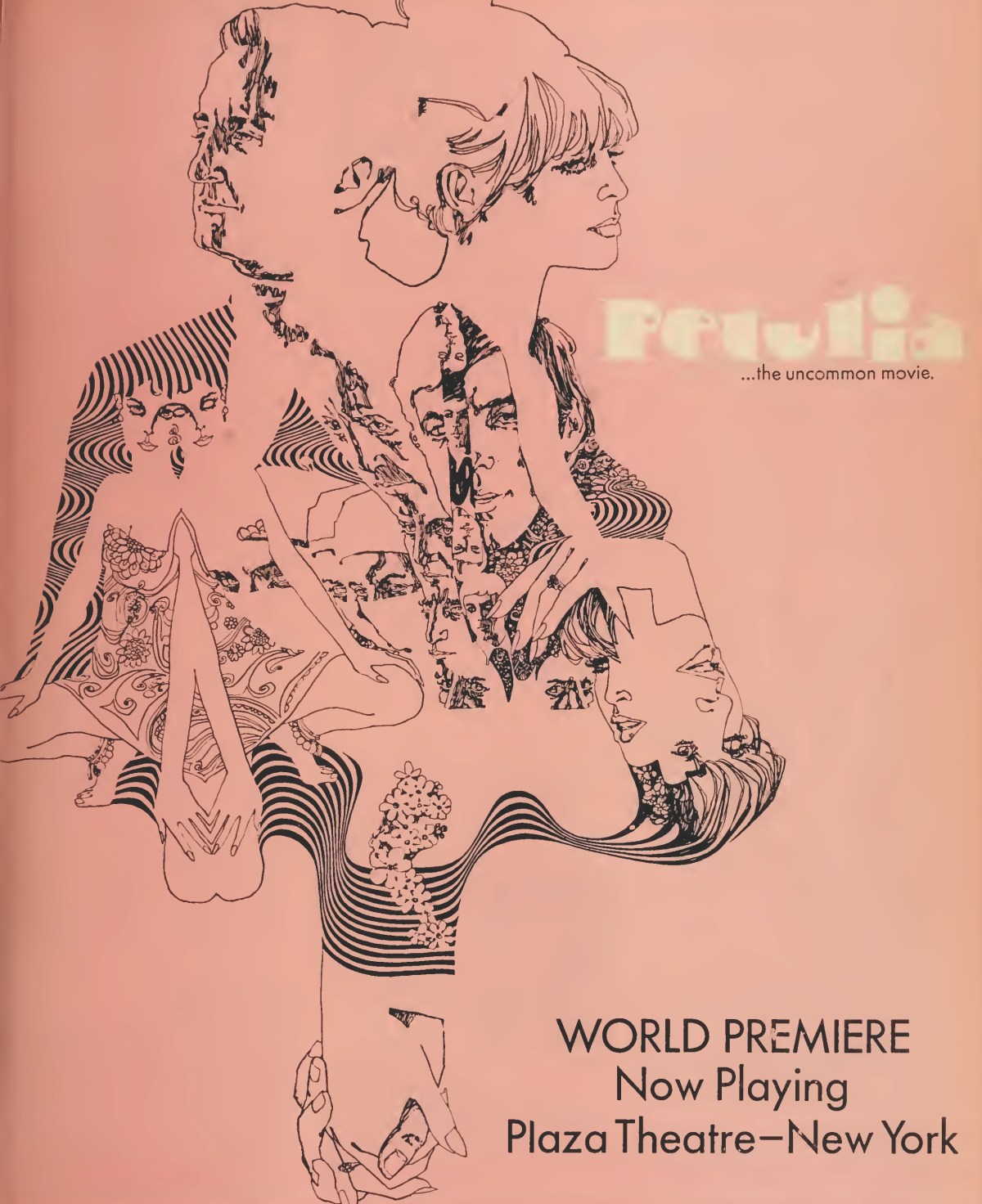

Check out a Behind the Scenes on this film’s Pressbook.

I like this one and have it on my hard drive; it’s not perfect, but Christie is always good to watch, and Lester, whatever his faults, at least is always up to something visually…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very tricksy visually and what about those nuns. Christie always very watchable. I thought Scott was the surprise package, not his usual persona at all.

LikeLike

Today’s:

“On 18 Feb 1966, a DV news item indicated that producer Raymond Wagner had approached actor James Garner to star in Me and the Arch-Kook Petulia, based on the soon-to-be-published novel of the same name by John Haase. The following month, a 7 Mar 1966 DV brief announced that Julie Christie would star in the picture, to be directed by Richard Lester. A distribution deal was said to be in the works, and Warner Bros.—Seven Arts, Inc.’s involvement was confirmed in the 14 Apr 1966 DV, which named James Garner as Julie Christie’s co-star. The 23 May 1966 DV also noted that Paul Newman was being sought for a role, but neither Garner nor Newman appeared in the final film.

As stated in the 5 Nov 1967 LAT, the title was briefly changed to Romance before the final title change to Petulia.

The project was considered a U.S.–Great Britain co-production, partly because Richard Lester’s company, Petersham Films, was based in England, as mentioned in the 6 Jul 1966 Var. However, since production took place in the U.S. and Mexico, and the crew was not entirely British, Petulia did not qualify for England’s Eady Plan subsidy. Lester, who was born and raised in the U.S. but was a resident of England at that time, was classified as British by the Directors Guild of America (DGA), as stated in the 15 May 1968 Var, which identified eleven other crew members as British: executive producer Denis O’Dell, director of photography Nicolas Roeg, camera operators Paul Wilson and Freddie Cooper, film editor Antony Gibbs, assistant editor Kevin Connor, production designer Tony Walton, design consultant David Hicks, wardrobe mistress Diane Jones, continuity person Rita Davison, and composer John Barry.

The setting of John Haase’s novel, in and around Los Angeles, CA, in the areas of Balboa, Santa Monica, and Hollywood, was moved to San Francisco, CA. In the 30 Apr 1967 LAT, Richard Lester was quoted as saying that Los Angeles was “too powerful a city” for the “sad love story,” and that he considered San Francisco a “more subtle” backdrop. Other cities considered before San Francisco were London, England; Rome, Italy; and Paris, France. Principal photography began in San Francisco on 10 Apr 1967, according to a 28 Apr 1967 DV production chart. In the 18 Mar 1968 DV, the production was said to be “the first major studio attempt” to shoot a film entirely in San Francisco “without any studio work.” Locations included the Filbert Steps, the Embarcadero, the Presidio, Fort Scott, Tiburon, Sausalito, Muir Woods, and the Fairmont San Francisco ballroom, according to items in the 30 Apr 1967 LAT and 26 May 1967 DV. Eleven weeks in San Francisco were set to be followed by one week of shooting in Tijuana, Mexico.

The 5 Apr 1967 and 12 Apr 1967 Var stated that Kim Hunter and Diana Hyland had been cast. The rock and roll band, Jefferson Airplane, was also slated to appear in the picture, according to a 21 Apr 1967 DV item, and a restaurant maitre d’ named Moreno was cast as himself, the 5 May 1967 DV stated. John Wasserman, a drama critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, reportedly acted as George C. Scott’s stand-in “to get an inside view of Lester’s technique,” as noted in the 10 May 1967 DV.

In an article about Sean Connery’s upcoming picture, Shalako (1968, see entry), the 21 Jun 1967 Var stated that Connery had just completed filming Petulia. No other mention of Connery’s name in association with the production were found in contemporary sources.

During filming, Haase planned to visit the set and write about his experiences for West magazine. However, Lester unexpectedly barred him, according to a 7 May 1967 NYT article, prompting Haase to write a scathing account of the project’s development in the 23 Jul 1967 LAT. In the article, the author stated that Robert Altman had initially been set to direct, at which point Haase had worked closely with Barbara Turner, who was attached as screenwriter at the time. Altman ultimately had to leave the project due to a conflicting television commitment, and Lester was brought on to replace him. After Lester hired Charles Wood to revise the screenplay, he asked Barbara Turner to write an additional draft, to return Petulia’s character to an earlier iteration. According to Haase, Turner vehemently disliked Woods’s script and briefly attempted to join forces with Haase to rescind the studio’s option on the novel. Haase expressed his own disappointment with the final screenplay, which Lawrence B. Marcus wrote, and was quoted in NYT as saying that “Petulia Danner’s” character had been turned into a “completely irresponsible nut.” Haase claimed the central love story was ruined, and that certain scenes were added only to highlight Lester’s talent as a director, including “scenes in a roller skating rink, bull fights, [and] two doctors having lunch in a topless restaurant.”

Petulia was scheduled to debut as a U.S. entry to the Cannes Film Festival on 22 May 1968, as noted in a 15 Apr 1968 DV item. Theatrical release followed at New York City’s Plaza Theatre on 10 Jun 1968. A Los Angeles premiere was scheduled to take place on 20 Aug 1968 at the newly refurbished Picwood Theatre, where general release followed the next day. After several months in theaters, an 8 Jan 1969 Var box-office chart listed domestic film rentals of $1.6 million, to date. The picture had initially been budgeted at $3.5 million, according to the 29 Nov 1967 Var.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Didn’t know they were looking at Garner, or Newman. Very interesting.

LikeLike