You get the impression this is the kind of movie that contemporary “visionary” directors think they are making when they focus on an unlikeable obsessive character causing chaos all around. It’s not just star quality they are missing – who wouldn’t give their eyeteeth for a Paul Newman to get behind a movie with poor commercial prospects, especially one tackling a sport that is guaranteed to put off the female element of the audience. Without Newman’s involvement you didn’t have a hope in hell of getting anywhere near the female audience.

And this was quite a different Paul Newman. In the first of his iconic roles, he’s far from the traditional hero. He’s an obsessive loner. But you are drawn towards him because of both the intensity and vulnerability of this character. He could as easily be the loser, the last thing an audience wants, he’s often accused of being, the bottler looking for an excuse for not going the extra mile it takes to win. And even when he does win, triumph comes with loss, of love and his avowed profession.

And it takes a heck of a confident director – Robert Rossen (Lilith, 1964) – to lock us into the dark prison of a pool room for virtually the first 30 minutes of the picture. If you don’t know the rules of American pool – as opposed to billiards and snooker – you’re not going to learn them here. “Fast” Eddie Felson (Paul Newman) has spent years on the road, hustling in small town poolrooms, to built up the kind of cash stack he requires to take on the greatest name in pool, Minnesota Fats (Jackie Gleason) whose unbeaten run stretches back a decade and a half.

And the movie should be over in that first half hour – or at the very least turned into a very different kind of picture, the one where the champ squanders his fortune – because Felson has thumped Fats. He’s $18,000 ahead at one point. In any other sport that should be mean he’s not just won but he’s won in style. Except it doesn’t work that way here. Fats has to concede. And Fats won’t concede because this is a marathon and despite his bulk Fats is better built for a 40-hour match than his slimmer opponent. And so it proves.

Felson is back to the beginning, welshing on his business partner Charlie (Myron McCormick) and heading out into the night. Where he meets alcoholic Sarah (Piper Laurie) who’s sitting in a bus station in the early morning sipping coffee until the liquor stores open. She’s not your usual easy pick-up, she knocks him back easily and in an idiosyncratic manner. She nearly does the same again, but relents and they start a relationship that’s built on nothing except ships passing in the night. She’s a lush, he’s a has-been. She’s a bit of a cultured lush, reads, writes short stories, but still booze is her first love.

If he’s not down enough, here comes the kicker. Thugs in a poolroom object to being hustled and break his thumbs. But she’s not very maternal and he’s not the kind of man who wants to be looked after in that fashion.

Eventually, he hooks up with another backer, a shady underworld character, Bert Gordon (George C Scott) whose first move is to break up Felson’s relationship, attempting to belittle Sarah, getting her smashed and putting the moves on her as if free sex is part of the deal. Felson gets badly hustled by wealthy Louisville Findley (Murray Hamilton), duped into playing billiards instead of pool, and the potential loss might well have slammed the door on the deal with Gordon. But Gordon gets his pound of flesh, literally, and Sarah, clearly better versed in the ways of the world than Felson, gives in to her lover’s manager and then is so disgusted with herself that she commits suicide.

Felson gains his revenge on both Minnesota Fats and Gordon but at a cost, lover lost, and kicked out of his profession. Victory has never been so negative.

While the acting all round is superb, all four principals plus the director Oscar-nominated, it’s the feel of the piece and the obsessiveness of the characters that resonates. Robert Rossen makes no concessions to the audience. He doesn’t explain the game and he doesn’t, as would be par for the course anywhere else, show how Felson learned how to handle a cue a different way after his thumbs were broken and there’s a distinct lack of the triumphalism that generally comes with the territory.

Behind the Scenes article tomorrow.

A big one:

“A 24 Apr 1959 DV news brief announced that writer-director-producer Robert Rossen had purchased film rights to Walter S. Tevis’s novel, The Hustler, published that year by Harper & Brothers. United Artists (UA) was set to produce and distribute the film, which would begin shooting in Sep or Oct 1959 in New York City. Over a year later, the 1 Sep 1960 DV stated that Rossen and UA Vice President Robert F. Blumofe would soon meet to discuss plans for filming, scheduled to begin later that year. Sidney Carroll was said to be at work adapting the script.

Singer Bobby Darin was named as a contender for the role of “Eddie Felson” in a in a 23 Sep 1960 DV column, but the part went to Paul Newman, as announced in the 3 Nov 1960 DV. Piper Laurie’s casting was reported later that month, in a 25 Nov 1960 DV item, and Jackie Gleason was named as a co-star in the 17 Jan 1961 DV, which stated that Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation was now the studio behind the film. By 27 Jan 1961, George C. Scott had been cast in the role of “Bert Gordon,” according to a DV published that day.

The 11 Jan 1961 DV listed a production start date of 27 Mar 1961, while later DV items indicated that principal photography would begin in Feb 1961. Location scouting reportedly took place in New Orleans, LA, according to the 27 Jan 1961 DV; however, filming took place entirely in New York City, beginning 6 Mar 1961, as noted in various sources including the 3 Mar 1961 DV. Three weeks of rehearsals had preceded principal photography, according to a 26 Nov 1961 NYT article, and the actors continued to sneak in extra rehearsals during production, according to Newman.

Location filming was based around the 8th and 9th Avenue area in Manhattan’s Broadway district, as stated in a 16 Feb 1961 DV “Just for Variety” column. The 19 Mar 1961 NYT named Ames Billiard Academy on West 44th Street as the primary location for pool hall scenes, and noted the use of a CinemaScope camera. Fifty-seven-year-old national billiards champion Willie Mosconi served as technical advisor. Prior to filming, Mosconi had spent two weeks instructing Paul Newman in pool technique. During production, the professional player performed some shots, and arranged balls for the actors. Jackie Gleason claimed to have been a “pretty good” player at one time, but acknowledged that his skills had lapsed. Other New York City locations included a Greyhound Bus Terminal in midtown Manhattan, and a restaurant on 8th Avenue. Interiors were filmed at Twentieth Century-Fox’s Movietone Building. As noted in a 25 Apr 1961 DV brief, while filming was underway, Rossen cast fifteen real-life socialites to play high society background actors.

Two New York City electrical inspectors solicited a bribe from the filmmakers during the shoot. An article in the 22 Mar 1961 NYT reported that Joseph Mintzer and Anthony Angelo, who worked for the Department of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity, were arrested on charges of extortion and bribery after an account of their misconduct was sent anonymously to a post-office box set up by Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr., for citizens to report “graft or unethical conduct by city employees.” Mintzer and Angelo allegedly promised to overlook electrical violations at the Ames Billiard Academy if Twentieth Century-Fox agreed to pay them $100 per day. Undercover policemen, posing as crewmembers, investigated the graft for two weeks before arresting the men on set.

The budget was cited as $1.5 million in the 19 Mar 1961 NYT, and later as $1.8 million in a 23 Oct 1961 DV item. Newman was reportedly promised a percentage of profits in addition to his salary, while Gleason received a flat $75,000 for three weeks’ work.

The title was changed during production to Sin of Angels, as announced in the 15 Mar 1961 DV. Shortly after, the 24 Mar 1961 DV reported that the new title was not “sitting well” with Rossen and would likely be changed back. A 28 Mar 1961 DV item stated that UA had contested the new title due to its similarity to The Sins of the Angels, which it had previously registered with the Motion Picture Association of America’s (MPAA) Title Registration Bureau. A 12 Apr 1961 DV brief confirmed the original title had been restored, and credited Fox and its branch managers with the decision.

Fred Hift, who had acted as publicity coordinator on Fox’s recent production of Francis of Assisi (1961, see entry), was said to be performing a similar role on The Hustler, according to an item in the 14 Feb 1961 DV. Promotions included personal appearances by Newman and Piper Laurie in multiple cities, as noted in the 29 Sep 1961 DV and 30 Sep 1961 LAT. Newman’s tour dates were “sandwiched in” between filming dates on Hemingway’s Adventures of a Young Man (1962, see entry), which was shooting in Ironwood, MI.

The picture opened 26 Sep 1961 at the Paramount Theatre, and Seventy-Second Street Playhouse, in New York City, according to various sources including the 15 Sep 1961 NYT. It became a commercial and critical success, grossing $59,000 in its first six days at the Paramount, the best showing at that theater since The Young Lions in 1958 (see entry), as noted in the 2 Oct 1961 DV. The 26 Nov 1961 NYT deemed the film a “sleeper” hit. Fox president Spyros P. Skouras expected the picture to gross upwards of $4 million domestically. Despite satisfying ticket sales, Newman reportedly accused Fox of being “too greedy for a buck” in its hasty rollout of the film. The actor believed that The Hustler should have been screened at a single art house theater for several months to build positive word-of-mouth, and shown at the Venice and Cannes Film Festivals before a wider general release. Nevertheless, Newman gave an interview published in the 1 Oct 1961 LAT, in which he claimed The Hustler was the first picture he had done that left him with no desire to re-shoot any scenes. Newman called the film “a corker” and credited it with giving him “the only satisfying feeling” he had had as an actor, to that time. A 2 Feb 1962 NYT article noted that Fox had been experiencing “financial difficulty” for over two years, and had lost roughly $13 million in the fiscal year 1961. However, the studio’s debt was said to have been slightly alleviated by the success of The Hustler.

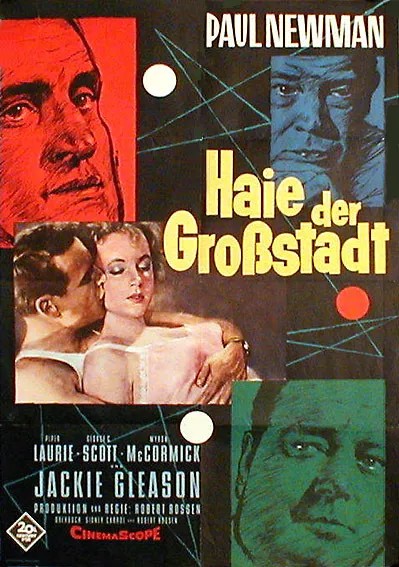

Complaints arose over print advertisements for the film, showing Newman “burying his face in Piper Laurie’s bosom,” as noted in a 16 Oct 1961 DV article. The Chicago Sun-Times reportedly received several complaints from readers, who alleged that the image paired with the title implied that the film was about a prostitute, not a “pool shark.”

The Hustler was ranked #6 on AFI’s list of the Top Ten Sports Films, and received numerous awards, including Academy Awards for Art Direction (Black-and-White) and Cinematography (Black-and-White); the New York Film Critics’ award for Best Director of the Year (Robert Rossen); the British Film Academy award for Best Foreign Actor (Paul Newman); and the Writers Guild of America (WGA) drama award for Rossen and Sidney Carroll’s screenplay. The picture was also named first runner-up for Best Motion Picture of 1961 by the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures, as noted in a 20 Dec 1961 NYT, and Film Daily poll awards went to Newman for Best Actor, Rossen for Best Director and Outstanding Scenarist, and George C. Scott for Best Supporting Actor, according to the 15 Jan 1962 NYT. Academy Award nominations went to Newman for Best Actor, Piper Laurie for Best Actress, Jackie Gleason and Scott for Actor in a Supporting Role, Rossen for Directing, Carroll and Rossen for Writing (Screenplay—based on material from another medium), and Rossen for Best Motion Picture. Golden Globe Award nominations included: Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama (Newman); New Star of the Year – Actor (Scott); Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role in Any Motion Picture (Gleason and Scott). As reported in the 7 Mar 1962 LAT, Scott requested that AMPAS rescind his Academy Award nomination, as he believed the annual awards ceremony had become a “weird beauty or personality contest” causing actors to “become increasingly award conscious.” AMPAS did not comply with Scott’s request, but informed the actor that he could refuse to accept the honor if he won. A rejection of the award would have been a first, but Scott lost to George Chakiris for West Side Story (1961).

As noted in a 3 Apr 1962 DV brief, The Hustler was shown as the U.S. entry at the Argentine Film Festival, where Newman was voted Best Actor.

Newman reprised the role of “Fast” Eddie Felson in Martin Scorsese’s The Color of Money (1986)), based on the novel of the same name written by Walter Tevis as a sequel to The Hustler.

Rudolph Wanderone, Jr., the professional pool player who was known as “New York Fats,” changed his name to “Minnesota Fats” after the character in this film.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, I’ve got a Behind the Scenes tomorrow.

LikeLike