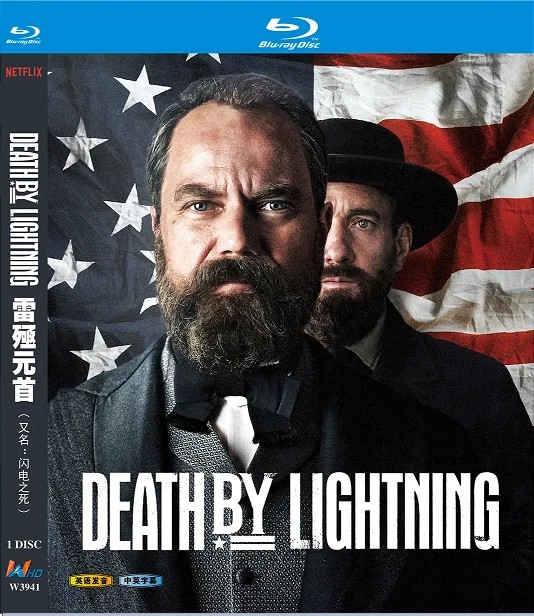

Streaming at its best. Take an obscure subject, a long-forgotten character, an incident that’s a mere blip in history, actors of less than middle rank in box office terms, and by breaking it down into easily consumable parts turn a history lesson that might be an indigestible three hours on the big screen into a riveting, enthralling drama of the highest quality that takes a no-holds-barred approach to politics

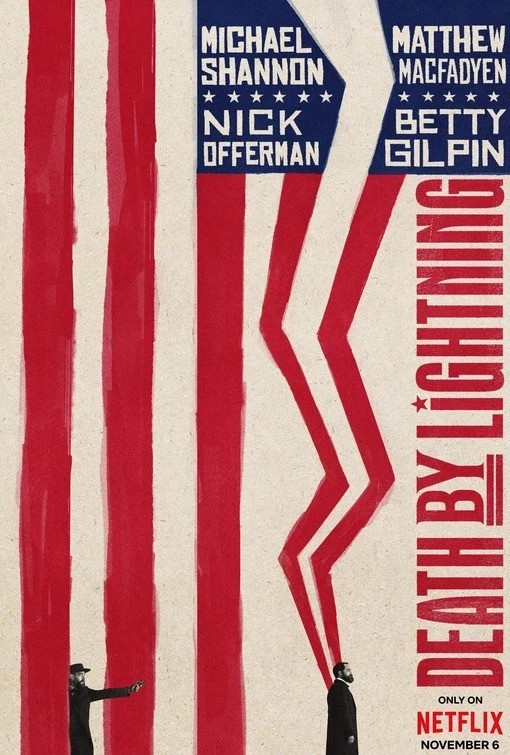

Small wonder you won’t have heard of U.S. President James Garfield (Michael Shannon) given he held office for around three months. Or of his misfit assassin Charles Guiteau (Matthew Macfadyen), less than a footnote in history for making the grave mistake of gunning down a President nobody had ever heard of.

Garfield shouldn’t even have been President. A mid-level politician on the verge of retirement, he wasn’t even in the running for the Republican nomination, which should have gone to Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant. But in one of those quirks of politics, the voters liked what they heard of Garfield and in a grass roots rebellion shooed him in. He won the Presidential election by a whisker.

And then his troubles started. He was too honest for the job. Unwilling to follow the standard corruption and hand out highly-paid posts to rank-and-file unfitting for the job, he found himself up against the New York political powerhouse headed by Roscoe Conkling (Shea Whigham) who controlled the bulk of the revenue entering the country. And the battles with Conkling would have easily made a House of Cards-style series in itself as the dueling politicians attempt to outwit each other.

But in the background, and weaseling his way into the foreground, is con man, thief, forger, misfit Guiteau with as much entitlement as could sink a battleship who, nonetheless, grasps the key essential of politics of the era which is that helping to grease the greasy pole is all you need to reap the benefits. Except his efforts to become anyone’s righthand man fall way short, as his ambition and lack of any relevant skills are widely mocked – he expects to be handed an ambassadorial role although he speaks no foreign languages – despite occasionally finding an opening.

Having been dismissed by the President himself, he decides Garfield is totally the wrong person for the highest position in the land and takes it upon himself to rid the nation of this burden. Even the assassination is ham-fisted and Garfield would have survived except for the efforts of the ham-fisted surgeon who killed him through septic poisoning.

That’s the climax to a thoroughly involving mini-series where no punches are pulled as far as politics are concerned. Conkling doesn’t mind being the man behind the throne as long as he gets credit for pulling the strings. Political wheeling-and-dealing has never been so ruthlessly exposed.

But it’s not as if Garfield is an innocent in that department. While not stooping to corruption, he pulls the legs from under Conkling by appointing Conkling’s righthand man Chester Arthur (Nick Offerman) as his Vice-President, a scheme that while initially backfiring eventually pays dividends. And it’s ironic that Conkling’s demise is down to a thwarted mistress.

The narrative switches on like a thriller, twists and turns every inch of the way. But as much as the riveting narrative, the joy of this is in the performances. Matthew Macfadyen, double Emmy award-winner for Succession (2018-2023), is rightly going to be considered to have landed the plum role, a fellow so much of a misfit that in a “free love” community nobody wants to have sex with him. But it’s a close-run thing. Michael Shannon (A Different Man, 2024) is outstanding, and Shea Whigham (F1, 2025) has immense fun especially with his eyebrows and dominating curl, while Nick Offerman (Civil War, 2024) in shifting from oaf to man of honor has a peach of a role, not forgetting Betty Gilpin (The Hunt, 2020) as the straight-talking wife of the President.

None of these are stars, not even of the indie persuasion, and yet it’s amazing what they can do with their characters.

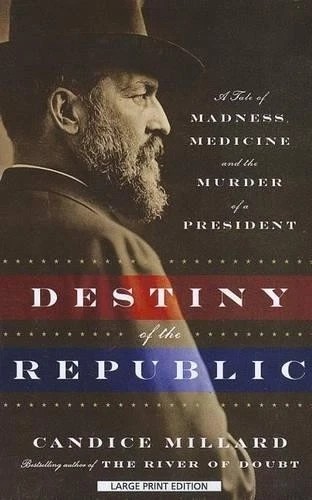

Directed with effortless style by Matt Ross (Captain Fantastic, 2016) from a script by Mike Makowsky (Bad Education, 2019) adapting the bestseller Destiny of the Republic by Candice Millard.

Outstanding.