How this crispy-told beautifully-mounted character-driven western ever languished among the also-rans is beyond me. I suspect the specter of John Ford hung heavily over it in the eyes of critics at the time but it more correctly belongs to the cycle of Cecil B. DeMille westerns that told stories with a true historical bent. Often detrimentally compared to How the West Was Won (1963), which told a similar tale of endeavor, this movie deliberately lacks that movie’s inflated drama in which every incident was built up, not least influenced by the need for Cinerama effect, rather than seeking an authentic truth.

Plainly put, the difference is here there are no charges, no races, no fording of rivers in the wrong places. Native Americans are treated with respect. Above all, an epic crossing of the continent with fully-loaded wagons is necessarily going to be slow, risk avoided at all costs, and yet this is not without incident or character arc. In fact, the script is terrific, not just dialog that rings true, but among the elements brought into play are male rivalry, clash with authority, guilt, young love, revenge, vision, justice, America in embryo. That the movie maintains a stately pace, no fistfights descending into brawls, and a shock ending indicate a director in charge of his material.

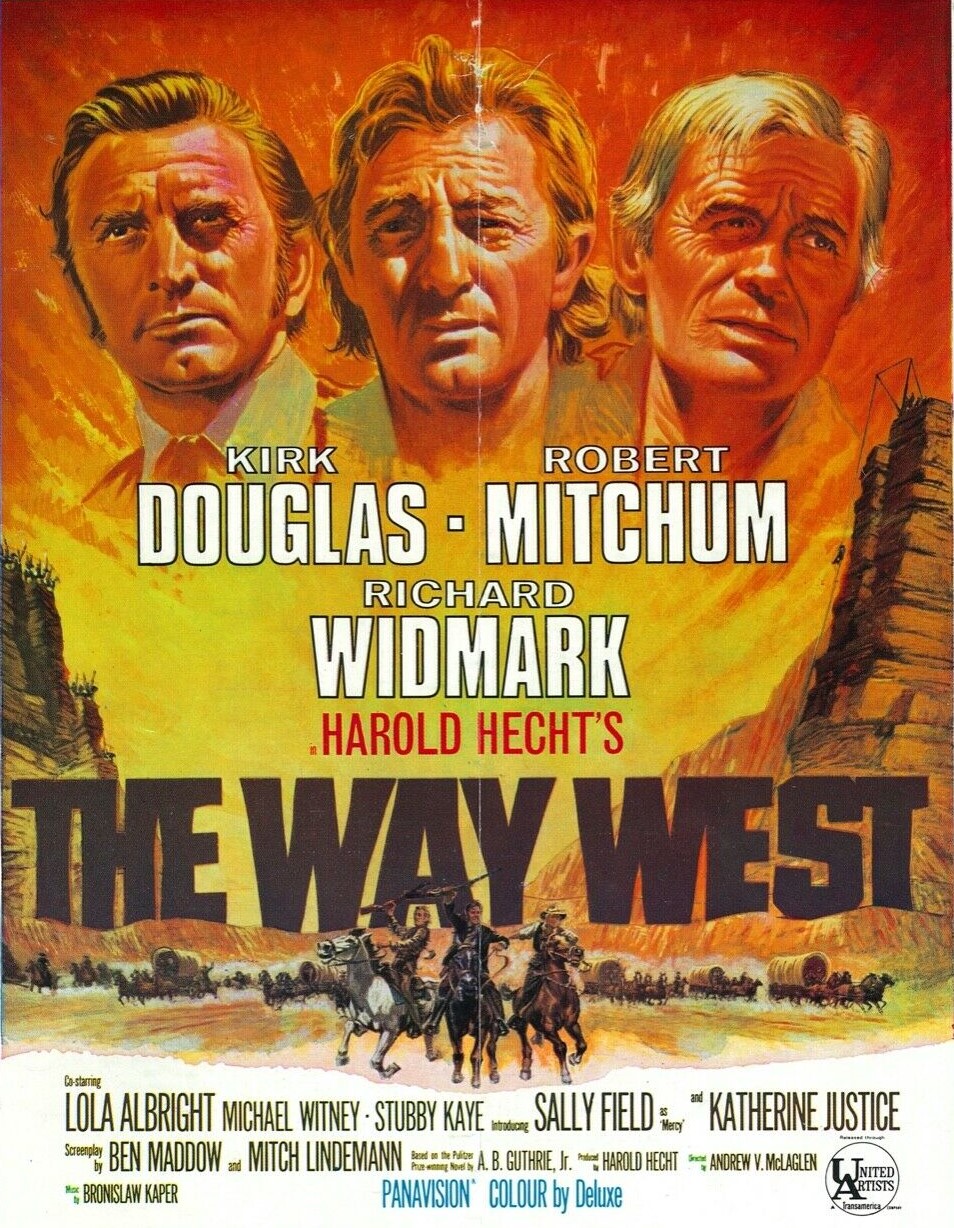

Based on A.B. Guthrie’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel set in 1843, the first wagon train heads for Oregon under the iron rule of Senator William Tadlock (Kirk Douglas) and guided by a scout with failing eyesight in Dick Summers (Robert Mitchum), both men widowed and in emotional limbo, and in the cantankerous company of Lije Evans (Richard Widmark) and his glamorous wife Rebecca (Lola Albright). There’s a stowaway (Jack Elam), a preacher who can’t afford the price of transportation, an illicit love affair between the vibrant and lusty Mercy (Sally Field) who “hankers after any three-legged boy” but makes eyes at married man Johnnie Mack (Michael Witney), and enough obstacles to keep less determined settlers from reaching their promised land.

Tadlock is the visionary, a politician suffering from an overblown estimation of his self-worth, who “might have been President except for a woman,” ruthless, valuing only his own ideas. “Point the way,” he tells Summers, “don’t gall me with opinions.” For fear it might interfere with his role as commander, he hides his vulnerability. There’s a plaintive moment when he shares his vision of a city with Rebecca, on the one hand full of his own importance, on the other clearly needing the pat on the back. Later, an occasion of death sees him falling prostate with grief on a grave and on breaking his own laws demands to whipped. The over confident blustering individual is by the end almost suicidal. What is a leader if there is no one to lead?

Summers stoically accepts his infirmity, constantly dropping his head so his eyes are hidden from sight under his hat as if his ailment could be easily detected, mourning the loss of his Native American wife, and while full of Western lore as easily passing on gentle wisdom about love, and his “lucky necklace” to an unrequited lover, but still accused of unworldliness, “for a smart man you ain’t got a lick of sense.” Evans bristles at any authority, believing independence means he goes his own way, especially if that permits the freedom to get drunk at a time of his choosing, and especially once he realizes such lack of inhibition riles the repressed Tadlock. But his fondness for alcohol triggers an incident that almost costs his son his life.

Celebrations he started catch the attention of the nearby Sioux and in the communal drunkenness a Native American child is accidentally killed. In the best scene in the film battle Sioux seeking justice and intent on attack are thwarted only by the “sacrifice” of the killer.

The picture is packed full of incident, many characters coming alive in a single shot or with one line of dialog. A woman tramps on her husband’s foot to prevent him challenging Tadlock’s authority. A woman with a baby retorts that she is afraid when bolder settlers facing potential Native American attack assert the opposite. The bravest man in the camp, the first volunteer to be lowered down a canyon, dies when his rope snaps.

There are any number of reversals. Buffalo, instead of being a danger and prone to stampede, create a dust cloud to hide behind. Rivers are crossed at sensible points, rapids avoided. An African American whips a white man. A boy becomes a man through honor rather than violence. Stories, large and small, play out in a succinct script.

Kirk Douglas (The Arrangement, 1969) is superb as a man whose iron core deserts him. Robert Mitchum (Secret Ceremony, 1969), in almost a supporting role, excellent in full awareness that the sight on which his reputation and job depend will vanish, brings a subtlety to his performance that would be recognized as ideal for Ryan’s Daughter (1970). Richard Widmark (The Bedford Incident, 1965), who is generally simmering, gets to mix in a bit of fun in with the simmering.

Lola Albright (A Cold Wind in August, 1961) swaps seductiveness for sense. In her debut Sally Field (Smokey and the Bandit, 1977), filled with zip and zest, sparkles as the lusty young woman and it’s astonishing to realize she would not make another movie for nearly a decade while another debutante Katherine Justice (Five Card Stud, 1968) finds her inner fire when it’s too late. There’s supporting talent a plenty – Jack Elam (Once Upon a Time in the West, 1968), Stubby Kaye (Cat Ballou, 1965), Harry Carey Jr. (The Undefeated, 1969) and William Lundigan (The Underwater City, 1962) in only his second film of the decade.

Director Andrew V. McLaglen (The Rare Breed, 1966) captures the correct tone for the film, making up for the essential slow pace with brilliant use of widescreen, coaxing great performances from all concerned. Screenwriters Ben Maddow (The Chairman, 1969) and Mitch Lindemann (The Careless Years, 1957) compress Guthrie’s tome with considerable skill.

Woefully underrated at the time and since, this deserves reassessment. This is a truer version of how the west was won. And I surely can’t be alone in demanding that McLaglen’s talent be more properly recognized.

You might be interested to know there are two other articles on this film – a “Behind the Scenes” and a “Book into Film.”

Some bits:

The Way West is based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same name, the second book in a trilogy written by Alfred Bertram Guthrie, Jr. (a.k.a. A. B. Guthrie, Jr.). The trilogy began with The Big Sky, which RKO adapted for the screen in 1952 (see entry) with director Howard Hawks and star Kirk Douglas; the last installment was These Thousand Hills, produced by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1959 (see entry). Producer Harold Hecht began planning his screen adaptation of The Way West in 1952, according to an article in the 20 Jul 1966 LAT. Hecht’s company with actor Burt Lancaster, Hecht-Lancaster Productions, added the project to its 1954-1956 slate of films to be released by United Artists (UA), as noted in the 8 Feb 1954 DV.

Items in the 19 Jan 1956 DV and NYT announced that Clifford Odets had been hired to write the screenplay as part of a multiple-picture deal with Hecht-Lancaster. With Burt Lancaster set to star, the 13 Apr 1956 DV noted that Gary Cooper and James Stewart were under consideration for co-starring roles. The anticipated budget was cited as $4 million in a 6 Mar 1956 DV brief, and later as $5 million in the 31 Dec 1956 DV, which claimed The Way West was poised to be the most expensive production ever undertaken by Hecht and Lancaster’s company, now Hecht-Hill-Lancaster Films, Ltd.

The 9 Nov 1956 DV stated that John Ford was in talks to direct. The following year, a 19 Sep 1957 DV brief noted that Hecht-Hill-Lancaster had recently learned of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s (MGM) plans to make a film titled The Trail West. In response, Hecht-Hill-Lancaster filed a formal protest with the Motion Picture Association of America’s (MPAA) Title Registration Bureau to stop MGM from using the similar title.

The script for The Way West remained in development, and on 6 Jun 1958, NYT reported that John Twist, on loan from Warner Bros. Pictures, would begin collaborating on the script with Marvin Borowsky that month. By fall 1958, John Gay had replaced Twist and Borowsky, according to the 22 Oct 1958 Var. Around that time, Kirk Douglas joined the cast, and actresses Deborah Kerr, Susan Hayward, and Wendy Hiller were considered for top female roles, as noted in the 2 Jul 1958 Var and 6 Jan 1959 DV. Over a year later, an item in the 24 Mar 1960 LAT announced that John Saxon had accepted a part.

The project lapsed for several years after the dissolution of Hecht-Hill-Lancaster, but UA retained screen rights to Guthrie, Jr.’s novel. On 9 Feb 1966, DV noted that Hecht was again in the planning stages on The Way West, and had recently reached out to Max von Sydow to star. A 22 Mar 1966 DV article confirmed that UA and Hecht had set a new deal to make the picture, and the following day’s DV attributed the latest version of the script to Ben Maddow and Irving Ravetch, adding that Andrew V. McLaglen was on board to direct. Maureen O’Hara was said to be under consideration for a role, and the 8 Apr 1966 DV also listed Frankie Avalon as a potential cast member.

A production chart in the 17 Jun 1966 DV indicated that principal photography had begun on 7 Jun 1966. Filming took place entirely in Oregon, with locations in the cities of Eugene, Bend, and Burns, according to a 25 May 1966 DV item. Near Bend, Ft. Rock in the Deschutes National Forest stood in for Independence Rock in Wyoming, as noted in the 20 Jul 1966 LAT, and outside Burns, a buffalo stampede sequence was shot using a herd of 450 buffalo. The 25 May 1966 DV stated that 200 Native Americans from the Warm Spring tribe had been hired as background actors.

An item in the 26 Aug 1966 DV announced that filming was completed two days ahead of schedule, on 25 Aug 1966. Editing was done at Goldwyn Studios in Hollywood, CA, the 3 Sep 1966 LAT reported, and an item in the 23 Jan 1967 DV indicated that a song called “Mercy McBee,” written by the film’s composer, Bronislaw Kaper, and Mack David, would be recorded by The Serendipity Singers for use in the soundtrack.

Although filmmakers had initially planned to premiere the picture in Eugene, a 3 Jun 1967 LAT article noted that The Way West debuted in New York City, instead. Citizens of Eugene were reportedly upset by UA’s broken promise to host a premiere in the city, but the first West Coast showing of the film was still expected to take place there.

The Way West was chosen as Picture of the Year by the National Congress of the Daughters of the Revolution, according to a 7 Mar 1967 LAT brief. It went on to receive negative reviews in the 17 May 1967 Var, 25 May 1967 NYT, and 19 Jul 1967 LAT. In a 5 Nov 1968 DV interview, Kirk Douglas registered his disapproval of the final film, calling it “a terrible disappointment.”

LikeLike

Thanks very much.

LikeLike