Producer Elliott Kastner had been angling to make a picture with close friend Warren Beatty for several years and already two highly-touted projects had bitten the dust – Honeybear, I Love You with a screenplay by Charles Eastman and Boys and Girls Together adapted from the William Goldman bestseller with Joseph Losey (Accident, 1966) lined up as director and filming set to begin in May 1965. Beatty was also first choice for comedy The Bobo (later filmed with Peter Sellers) when Kastner was trying to get that off the ground in 1965,

Like Carl Foreman (The Guns of Navarone, 1961) before him, Kastner had moved to London in a bid to find his production feet, setting up an office there in 1964, and living in a suite in the five-star Connaught Hotel for 14 months. He had commissioned a screenplay from Bob and Jane Carrington (Wait until Dark, 1967), their first work for the movies. Despite his close relationship with Beatty, he eyed up Frank Sinatra for the leading role of Barney Lincoln in Kaleidoscope. He cold called the actor at Goldwyn Studios. Sinatra operated out of a bungalow there and, while working an agent for MCA, Kastner knew his way around the locale, meeting up with the likes of Marilyn Monroe, William Holden, Gregory Peck, Billy Wilder and John Huston.

Sinatra liked the screenplay. His only concern was how to fit into proceedings a shot of his Lear jet (which presumably he would hire out to the production). “The main thing yet to be done to the script,” he instructed the writers, “is to insert one Lear jet.” He suggested ways this could achieved – seen in the title sequence or flying the main character to France.

A bigger immediate problem was that Sinatra didn’t have an agent and his deals were made by his lawyer Mickey Rudin. With Sinatra potentially on board, Warner Bros was keen to back the picture. With his partner Jerry Gershwin, Kastner visited Rudin in his office at Gang, Tyre, Rudin and Brown in Los Angeles. But the meeting didn’t go as planned – nor followed the usual Hollywood pattern. Instead of the star being signed up by the producers, Rudin wanted it to go the other way around, the producer surrendering the property.

Kastner complained to the attorney, “It’s our project. We own it and the way you’re placing this negotiation is that you will agree to what fees and what points we want and it’s your picture and we work for you.” Despite Gershwin’s protests, Kastner ended the meeting.

Oddly enough that suited Kastner. He planned to replace Sinatra with Warren Beatty. Which was a pretty odd calculation given Beatty’s last five pictures – The Roman Spring of Mrs Stone (1961), All Fall Down (1962), Lilith (1964), Arthur Penn’s Mickey One (1965) and Promise Her Anything (1965) – had all been flops. “The vicissitudes of the industry are the same now as they were then,” explained Kastner, “if you are a movie star you can stay a movie star as long as you don’t have four flops in a row. Nobody really wanted Warren, including my partner who hated him.”

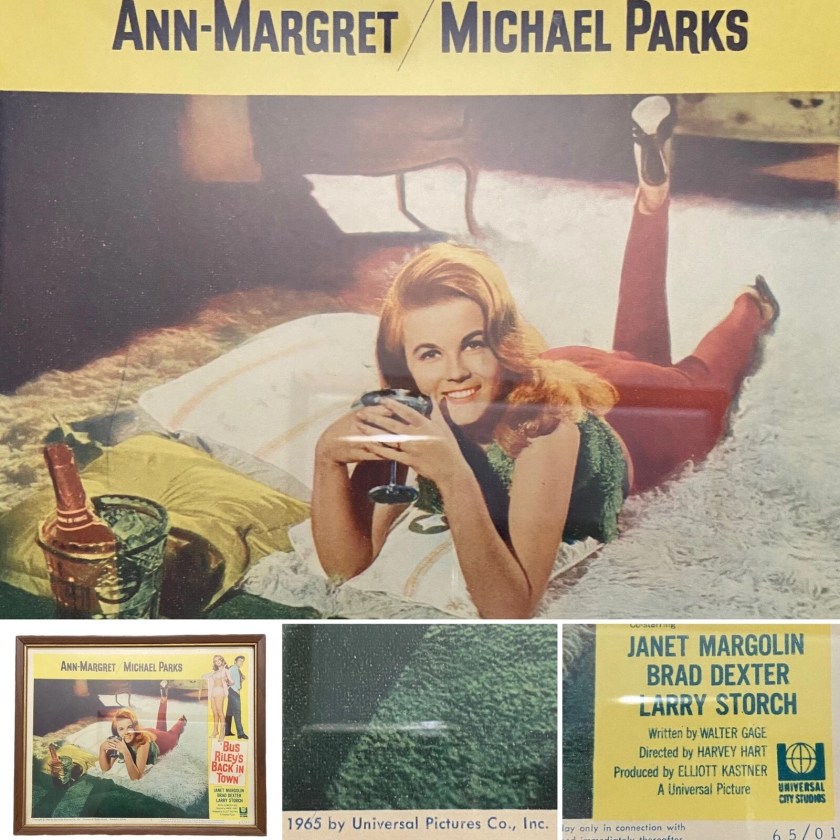

Jack Warner was of the opinion that nobody turned down Frank Sinatra and that Kastner should find a way to make a deal. When Kastner refused, Warner relented because he liked the script and because Kastner agreed to give the female lead to Sandra Dee (Come September, 1963) who had been groomed by Universal to take over from Doris Day who had flown the studio nest. Dee’s contract came with some unusual provisos – hotel accommodation for her mother and the son Dodd from her marriage to Bobby Darin. The $525 per week, additional to her salary, that Dee expected for incidentals was par for the courser, but not another $300 per week for her mother

But what really appealed to Jack Warner was the innovative deal. Kastner had invented what would be known as the “negative pick-up.” As long as Warner agreed on a set budget, he wouldn’t have to stump up a dime until the movie was finished. An incredulous Jack Warner asked, “You mean I don’t have to give you any money until you deliver the picture to me?”

Which meant Kastner, who had nothing like that amount of money to hand, had to find the finance. Using Warner’s agreement as collateral, he persuaded the United California Bank to lend him $1.6 million. The only proviso was that Kastner find a completion guarantor. Kastner turned to Film Finance in London and won its approval.

In fact, Beatty was not the only actor under consideration. Also on Kastner’s short list were bigger stars of the caliber of Burt Lancaster (Elmer Gantry, 1960), Steve McQueen (The Great Escape, 1963), Sean Connery (Woman of Straw, 1964), Peter O’Toole (Lawrence of Arabia, 1962) and Paul Newman (The Hustler, 1961). For the female lead, the producer was eyeing up Jane Fonda (Cat Ballou, 1965), Julie Christie (Doctor Zhivago, 1965), Brigitte Bardot (Contempt, 1963) or Tuesday Weld (The Cincinnati Kid, 1965).

The likes of Yul Brynner (The Magnificent Seven, 1960), Rod Steiger (The Pawnbroker, 1964), Jack Hawkins (Masquerade, 1965) and Kenneth More (Sink the Bismark!, 1962) were suggested for main supporting roles. Megging duties could have fallen to Brian G. Hutton (The Wild Seed, 1965), Bryan Forbes (King Rat, 1965), Richard Lester (A Hard Day’s Night, 1964), Clive Donner (What’s New, Pussycat?, 1965) or Karel Reisz (Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, 1960).

Although Warren Beatty had failed to capitalize on the early promise of Splendor in the Grass (1961) he wasn’t short of interesting offers including Youngblood Hawke from the Howard Wouk bestseller, John Updike’s Rabbit, Run, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter adapted from the Carson McCullers novel – all films that were ultimately made but minus Beatty. He turned down Is Paris Burning? (1965) and walked away from What’s New, Pussycat? (1965), a massive hit. “All this talk about Beatty being difficult, refusing scripts etc is nonsense,” averred producer Charles K. Feldman, “I think he’s smart.”

Beatty had his own idea what he wanted to do and set up Tatira Productions to avoid “studio dictatorship” and interference. First project was Mickey One, a co-production with Arthur Penn, a $1 million flop. He claimed he had projects lined up involving screenwriters Elaine May – longer-term she wrote Ishtar (1987), a monumental flop – and Budd Schulberg but nothing resulted from that arrangement.

So in some respects the future of Beatty’s career appeared to depend on Kaleidoscope. However, once the deal was done and the papers signed, Beatty agitated to replace Sandra Dee with Susannah York (Sands of the Kalahari, 1965), whom Kastner had originally suggested. “Now I had to double cross my partner, double cross Jack Warner and double cross Sandra Dee. All of which I did.” Kastner settled with Dee for $50,000, paid out of his own pocket.

Initial budget was set at $1.65 million – though this increased to $1.8 million – and for guaranteeing the production Film Finance charged $21,906 payable within 14 days of the first day of shooting. Beatty received $100,000 plus 5% of the gross.

Kastner handed directing duties to Jack Smight who had just made Harper for him. Smight was on roll, having set up a production company. With writer James Lee, he owned the rights to Rabbit, Run and American Dream by Norman Mailer. He had a five-picture deal with WB and was hoping to pair William Holden and Julie Christie in The Lonely Side of the River.

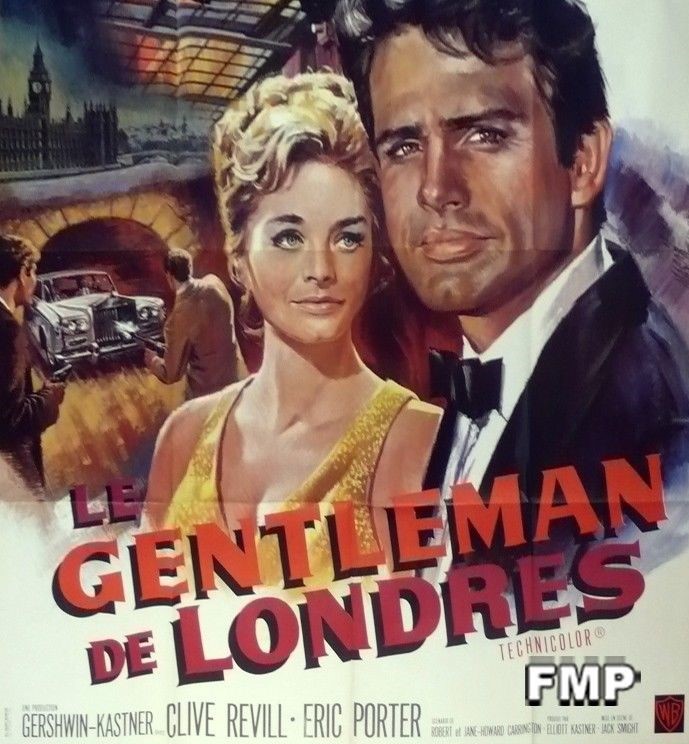

The cast was filled out with British dependables like Clive Revill (The Double Man, 1967) and Eric Porter (The Lost Continent, 1968) and model Pattie Boyd, future wife of Eric Clapton and George Harrison, in a bit part. Beatty was “totally professional” although Kastner noted “he turned out to be a piece of shit later on.” Future director Peter Medak (Negatives, 1968) acted as associate producer.

Shooting “went fairly smoothly” at Pinewood and on location in Monte Carlo and Eze in the South of France and despite one day of reshoots on the Corniche thanks to cloudy weather the picture came in ahead of schedule and only slightly over budget.

Only when it came to the financial reckoning with Jack Warner was Kastner’s astuteness obvious. He and Gershwin took home $500,000 – around a third of the total budget. In essence the movie had cost around $1.3 million. So whether the movie was a hit or not (it wasn’t – rentals came to little more than $1 million) – and that would depend to a large extent on the amount Warner spent on advertising and promotion – Kastner walked away with a fortune.

SOURCES: Elliott Kastner Memoir, courtesy of Dillon Kastner; Elliott Kastner Archives, courtesy of Dillon Kastner; “Elliott Kastner’s Partner on Honeybear Is Warren Beatty,” Variety, January 23, 1963, p4; “New York Sound Track,” Variety, February 6, 1963, p7; Youngstein Sets Novel,” Variety, December 11, 1963, p5; “Dilemmas Already They Got,” Variety, June 24, 194, p13; Warren Beatty Firm Aim,” Variety, February 10, 1965, p3; “Warren Beatty Partner and Star of Goldman Tale Via Elliott Kastner,” Variety, March 31, 1965, p7; “Radical Kastner-Gershwin Policy: Get Scripts in Shape Way Ahead,” Variety, May 19, 1965, p19; “Clement Launches Is Paris Burning?”, Variety, July 21, 1965, p5; “Feldman Sees Beatty Director,” Variety, November 10, 1965, p15; “Landau-Unger On-The-Making,” Variety, November 17, 1965, p3; “Smight Starts Preparation of Kaleidoscope,” Variety, November 24, p4.