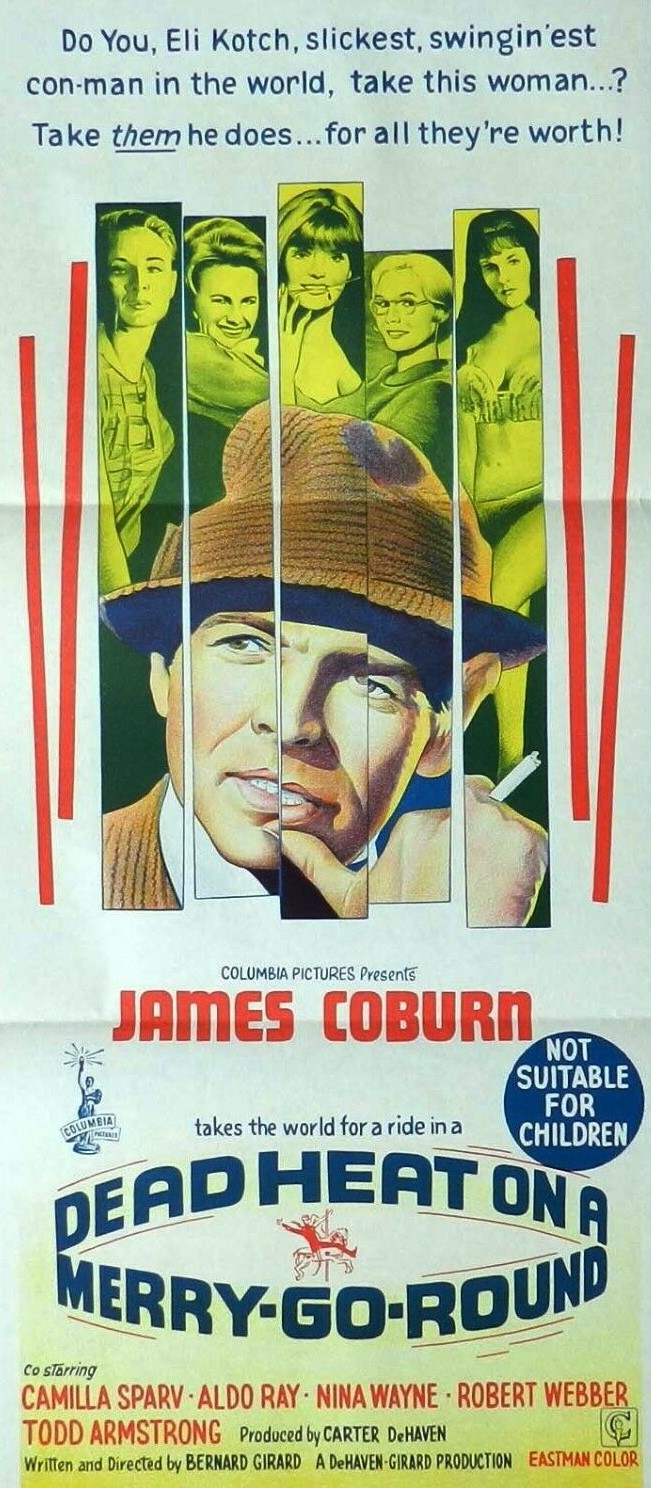

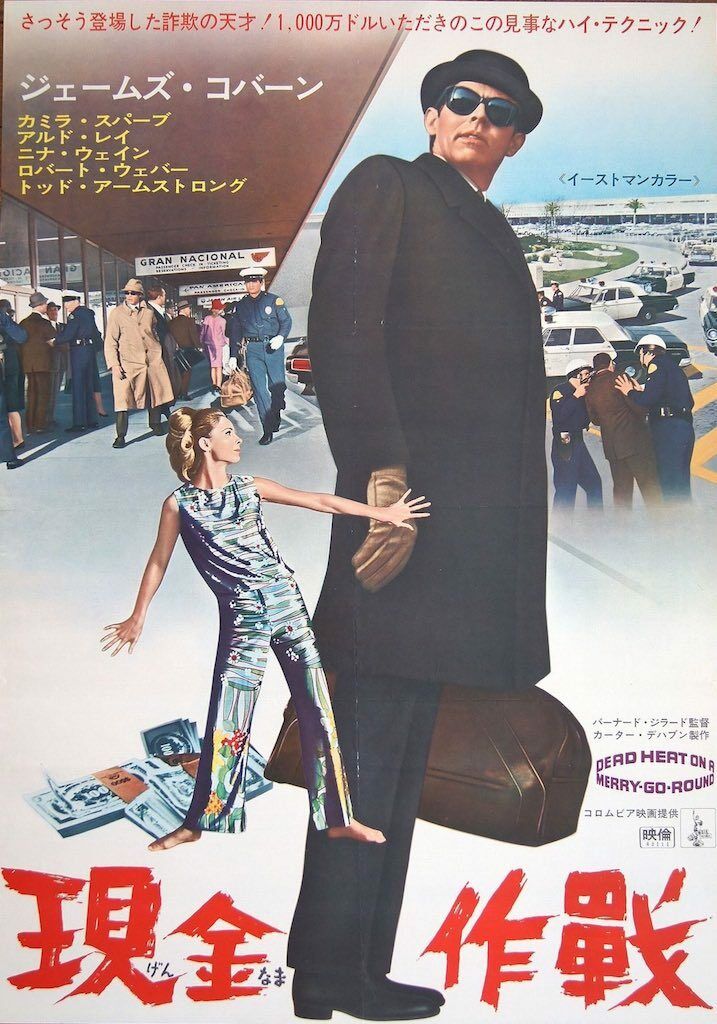

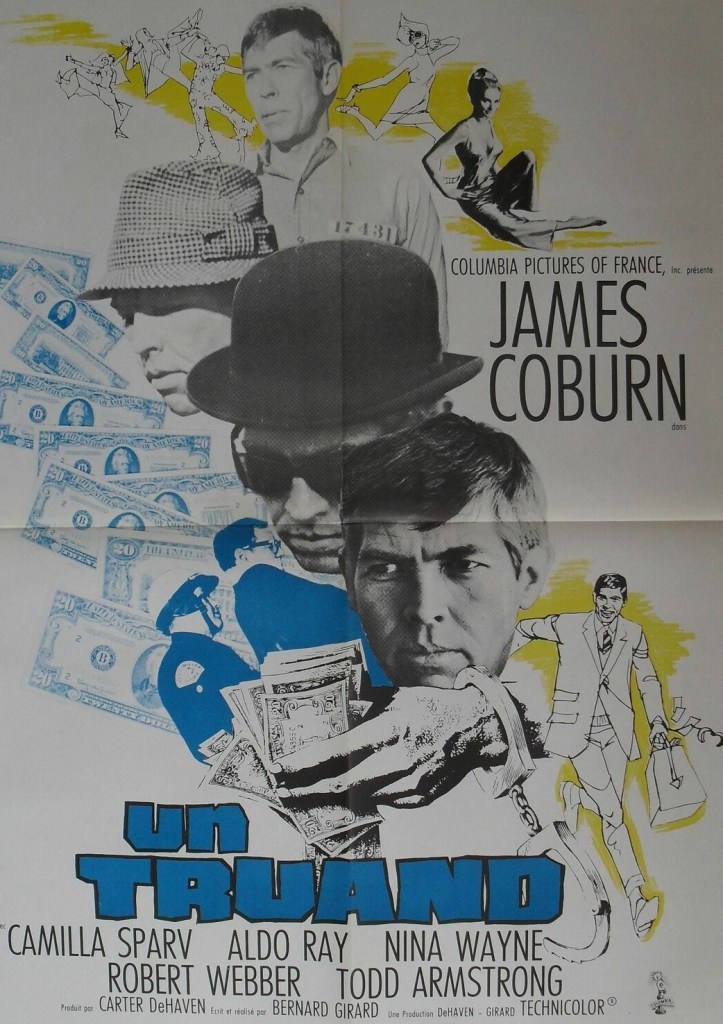

Highly entertaining woefully underrated heist picture with an impish James Coburn (Hard Contract, 1967), Swedish Camilla Sparv (Downhill Racer, 1969) in a sparkling debut and at the end an outrageous twist you won’t see coming in a million years. This is the antithesis of capers of the Topkapi (1964) variety. Not only is it an all-professional job, it takes a good while before you even realise the final focus is robbery or even the actual location. There are hints about the that event and glimpses in passing of material that may be used, and although the theft is planned to intricate detail, none of that planning is revealed to the audience.

The paroled Eli Kotch (James Coburn), who has seduced the prison psychiatrist, immediately skips town and starts fleecing any woman who falls for his charms. He changes personality at the drop of a hat, fitting into the likes of the mark, and in turn is burglar, art thief, car hijacker, in order to raise the loot required to buy a set of bank plans, and yet not above taking on ordinary jobs like shoe salesman to meet the ladies and coffin escort to get free travel across the country. So adept at the minutiae of the con he even manages to impersonate a hotel guest in order to get free phone calls.

He enrols girlfriend Inger (Camilla Sparv) to act as an amateur photographer working on a “poetic essay on transient populations” to get an idea of sites he means to access. He manages to have the head of a Secret Service detail blamed for a leak. Everything is micro-managed and his final masquerade is an Australian cop with a prisoner to extradite which provides him with an excuse to linger in a police station, privy to what is going on at crucial points.

If I tell you any more I’m going to give away too much of the plot and deprive you of delight at its cleverness. The original posters did their best not to give away too much but you can rely on critics on Imdb to spoil everything.

This is just so much fun, with the slick confident Eli as a very engaging con man, the supreme manipulator, and almost in cahoots with writer-director Bernard Girardin (The Mad Room, 1969) in manipulating the audience. There are plenty films full of obfuscation just for the hell of it, or because plots are so complex there’s no room for simplification, or simply at directorial whim. But this has so much going on and Kotch so entertaining to watch that you hardly realize the tension that has been building up, not just looking forward to what exactly is the heist but also how are they going to pull it off, what other clever tricks does Kotch have up his sleeve for any eventuality, and of course, for the denouement, are they going to get away with it, or fall at the last hurdle. There is a great twist before the brilliant twist but I’m not going to tell you about that either.

There’s plenty Swinging Sixties in the background, the permissive society that Kotch is able to exploit, and yet the film has some unexpected depths. You wonder if the memories Kotch draws upon to win the sympathy of his female admirers have their basis in his own life. You are tempted to think not since he is after all a con man, but the detail is so specific it has you thinking maybe this is where his inability to trust anyone originates.

Bernard Giradin was not a name known to me I have to confess, since he was more of a television director than a big screen purveyor – prior to this he had made A Public Affair (1962) with the unheard-off Myron McCormick – and Coburn was the only big star he ever had the privilege to direct. But there are some nice directorial touches. The movie opens with a wall of shadows, there are some striking images of winter, a twist on bedroom footsie, and jabbering translators. But most of all he has the courage to stick to his guns, not feeling obliged to have Kotch spill out everything to a colleague or girl, either to boast of his brilliance, or to reveal innermost nerves, or, worse, to fulfil audience need. There’s an almost documentary feel to the whole enterprise.

James Coburn is superb. Sure, we get the teeth, the wide grin, but I sometimes felt all the smiling was unnecessary, almost a short cut to winning audience favour, and this portrayal, with the smile less in evidence, feels more intimate, more seductive. This may well be his best, most winning, performance. Camilla Sparv is something of a surprise, nothing like the ice queen of future movies, very much an ordinary girl delighted to be falling in love, and with a writer of all the things, the man of her dreams.

The excellent supporting cast includes Marian McCargo (The Undefeated, 1969), Aldo Ray (The Power, 1968), Robert Webber (The Dirty Dozen, 1967), Todd Armstrong (Jason and the Argonauts, 1963) and of course a blink-and-you-miss-it appearance of Harrison Ford as the only bellboy (that’s a clue) in the picture. You might also spot showbiz legend Rose Marie (The Jazz Singer, 1927).