Clint Eastwood didn’t waste much time capitalizing on the unexpected success of the Dollars Trilogy. But the first was not released in the United States till 1967 and despite the success of the series across Europe was generally dismissed as a fluke, until American audiences suggested otherwise. The following year Eastwood appeared in three pictures, Hang ‘Em High, Coogan’s Bluff and Where Eagles Dare, which solidified his screen persona as portraying more with a twitch or a raised eyebrow than digging deep into the dialog.

Contrary to my expectations, Hang ‘Em High doesn’t quite fall into the trademark revenge mode of later westerns. It’s somewhat episodic, Jed (Clint Eastwood) often sent off on a tangent by Judge Fenton (Pat Hingle), allowing the lynch mob who failed to hang him in the first place a second chance at completing the job.

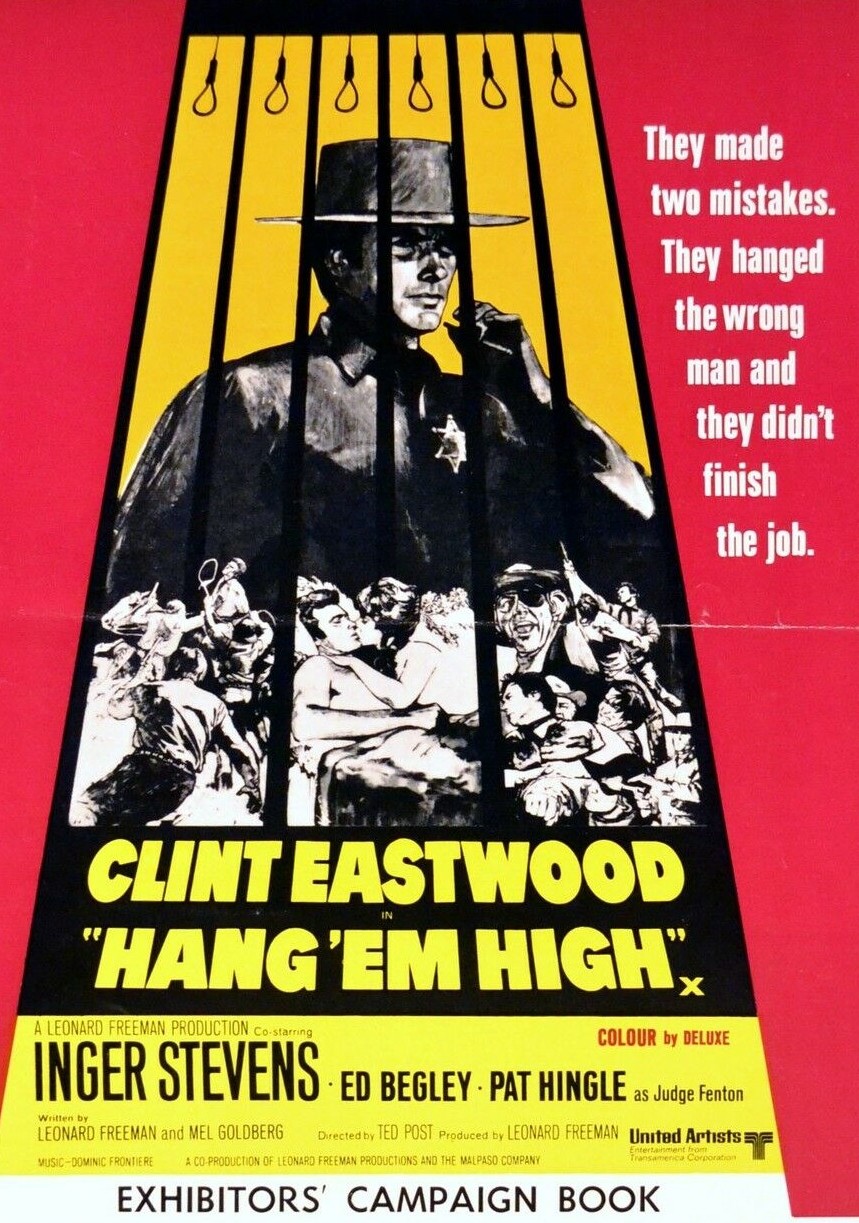

United Artists spun out its Clint Eastwood portfolio at every opportunity.

And while the presence of the second-billed Inger Stevens (Firecreek, 1968) suggests heady romance that doesn’t kick in until the third act and it’s more tentative than anything and its purpose is more, in narrative terms, to provide Jed with a correlative with which to compare his own obsession, bringing to justice the nine men who attempted to kill him.

Just to confuse things, the middle section isn’t about revenge or romance, but about justice. Specifically, it’s about showing that justice will be done, that in the unruly West, with insufficient enforcers of law and order, that crimes will not go unpunished, a gallows on constant display to make the point.

Surprisingly, it’s Jed who argues that some of this justice is just too summarily executed. He tries in vain to prevent the execution of two young rustlers who fell in with one of his potential assassins, Miller (Bruce Dern), but who refuse to take advantage of the situation when Miller overpowers Jed while he’s bringing the trio in to face the judge. Admittedly, they don’t go to his aid either, but the fact they resist piling in allows Jed to escape. However, rustling is a hanging offence, so they cannot escape the noose, certainly not in Fenton’s town.

There’s a switch in the mentality of Jed. Before he’s co-opted by Fenton to return to his former profession of lawman, Jed is of the school of thought that decides to take the law into his own hands. Even wearing a badge, you are allowed to shoot a man stone dead if he’s trying to escape, even if such action is severely hampered by him already being badly wounded, as lawman Bliss (Ben Johnson) demonstrates. But Bliss isn’t as callous as he sounds. He’s a contradiction, too, racing to the aid of Jed dangling in a noose in a tree, freeing him so he can face justice, even if that will most likely result in hanging.

So Jed upholds the law, preventing other citizens from taking the law into their own hands, Miller a target of the family of the owners he slaughtered before making off with their cattle.

We only see shop owner Rachel (Inger Stevens) fleetingly for most of the picture. She appears any time a new wagon load of criminals is jailed, scanning their faces for who knows what, though likely we’ve guessed it’ll be to find the killer of a loved one. Not only has her husband been killed by two strangers but while his corpse is lying on the ground beside her she’s raped. And although she eventually responds to Jed’s gentle moves, she still can’t let go of her “ghosts.”

Jed is put through the wringer. Not only an inch from death following the initial hanging but ambushed again by the same gang and nearly dying of pneumonia after being caught in a storm, the latter incidents permitting the kind of nursing that often fuels romance.

There’s an ironic ending. Captain Wilson (Ed Begley), leader of the gang, hangs himself rather than be shot by Jed.

The score by Dominic Frontiere (Number One, 1969) lurches. We go from heavy-handed villain-on-the-loose music to eminently hummable echoes of Ennio Morricone.

Clint Eastwood reinforces his marquee appeal, Inger Stevens delivers another of her wounded creatures, and Pat Hingle (The Gauntlet, 1977) is an effective foil. Bruce Dern (Castle Keep, 1969) does his best to steal every scene without realizing that over-playing never works in a movie featuring the master of under-playing.

Host of cameos include veterans Ben Johnson (The Undefeated, 1969), Charles McGraw (Pendulum, 1969) and L.Q. Jones (Major Dundee, 1965) plus two who had not lived up to their initial promise in Dennis Hopper (though he would revive his career the following year with Easy Rider) and James MacArthur (Battle of the Bulge, 1965).

Journeyman director Ted Post made a big enough impact for Eastwood to work with him again on Magnum Force (1973). Written by Leonard Freeman (Claudelle Inglish, 1961) and Mel Goldberg (Murder Inc., 1960).

More than satisfactory Hollywood debut for Eastwood and worth checking out to see that even at this early stage he had nailed down his screen persona.

Saw this in ’68. Even to my 13 year old self, I saw that it had a TV, studio back lot feel. Disappointed that it wasn’t like THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY.

Some more:

“The 10 Feb 1966 DV announced that Mel Goldberg had been hired to write the script for Hang ‘Em High, based on an original story idea from producer Leonard Freeman. Ted Post was hired to direct, and Clint Eastwood was cast in the role of “Jed Cooper,” as announced in the 3 May 1967 DV, which also stated that United Artists would release the picture.

Principal photography began 19 Jun 1967 in New Mexico, according to a 23 Jun 1967 DV production chart. Following location shooting in and around Las Cruces, NM, interiors were set to be filmed in rented space at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) studios in Century City, CA. On 8 Aug 1967, DV reported that the shoot would wrap that day.

An announcement in the 28 Jul 1967 DV stated that Doris Tsoong-Ying Nieh had been cast.

Clint Eastwood reportedly received a salary of $400,000, in addition to twenty-five percent of the film’s net profits, according to a 12 Jun 1968 Var brief. A 23 Apr 1969 DV item stated that the film cost $1.68 million, and went on to become a box-office success, grossing $15 million to that time.

Although the 17 Jul 1968 Var review deemed the picture “morbidly violent” and described hanging scenes as “shown in meticulous, morbid detail,” reviews in the 8 Aug 1968 NYT and 15 Aug 1968 LAT cited the final mass hanging sequence as the film’s dramatic and artistic high point. According to a 21 Jul 1967 DV article, the staged hangings represented a first “in that actual noose and gibbet were used, utilizing a tied-off section of the knot that prevented stuntmen’s neck[s] from breaking.” Stuntman coordinator Harvey Parry worked with special effects man George Swartz to design a special platform, which took four weeks to build. Parry “pre-tested the device” several times himself and admitted being anxious that something might go wrong. The gallows was fashioned after “authentic western and English types,” but the ten-foot “drop” was considerably higher than the standard 3½-to-4½-feet employed in real-life gallows, and 2½ feet in prop versions. Stuntmen who performed in the scene wore leg irons and hoods, with padding around their necks to prevent rope burns, and fell through a trap door onto padded boxes.

The picture was released on 7 Aug 1968 in New York City, and one week later in Los Angeles, CA, prior to the unveiling of the Motion Picture Association of America’s (MPAA) new rating system. However, when a reissue of Hang ‘Em High was released on a double bill with The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1967, see entry) in Jul 1969, the picture was given an “M” rating, or “suggested for mature audiences (parental discretion advised),” as noted in the 23 Jul 1969 Var.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Once again thanks for your digging.

LikeLike