Sets the tone for the later Sergio Leone, Sam Peckinpah and Clint Eastwood westerns in which the bad guys are the good guys and we find ourselves rooting for bounty hunters, gunslingers and bank robbers. Except this is more of a drama than a western. Shooting is kept to a minimum and instead it’s a character-driven drama about outlaws. Ostensibly, it’s a simple revenge tale and also totes around that later cliché of the honor code and principles that The Wild Bunch (1969) in particular put so much faith in.

But, in reality, it’s an in-depth look at two fascinating characters, both very human, both sly, self-indulgent, constantly attempting to reinvent themselves, cheat their way to a better life or to get what they want. There’s no sense of redemption, just obsession.

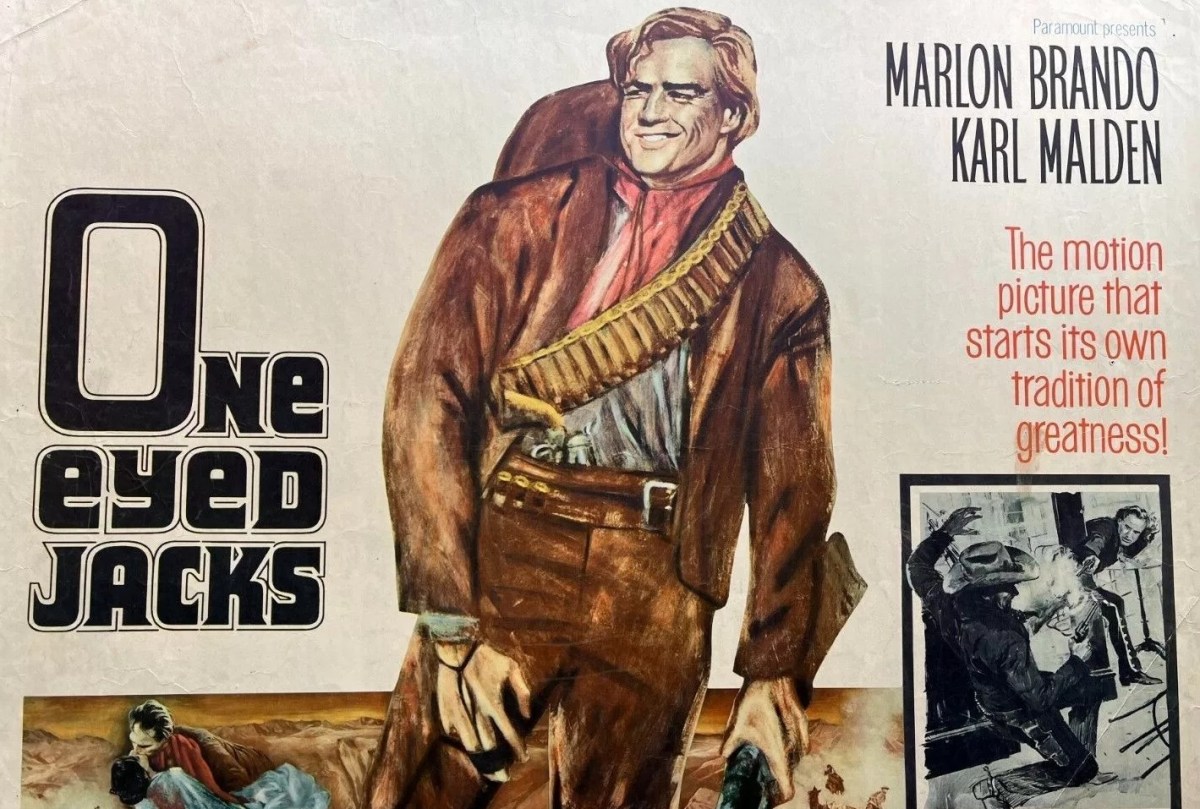

Rio (Marlon Brando) and Ben (Karl Malden) are bank robbers, the former a notorious gunslinger to boot and also partial to stealing pieces of jewellery to assist his practiced seduction routine whereby he claims a ring or necklace was a family heirloom, and he’s a good reader of the reluctant female because that tends to open the bedroom doors. Pursued after pulling off a job in Mexico, down to one exhausted horse and trapped by a posse, Ben is sent to get fresh horses but instead of coming back heads off with the loot. The captured Rio does a five-year prison stretch before escaping and seeking revenge.

Ben, meanwhile, has gone straight. He’s picked up a peach of a job as a lawman, a marshal no less, in Monterey on the California coast, where he’s made no secret of his past so he’s not prey to blackmail. He thinks Rio believes his story that he did all he could to return to aid his friend. We know different.

Rio has alighted on this town by pure accident, hooking up with a band of thieves led by Bob (Ben Johnson) who are set on robbing the bank here. Their plans are put in disarray when Ben takes revenge on Rio seducing his stepdaughter Louisa (Pina Pellicer) by subjecting him to a savage whipping and breaking his gun hand. It takes ages for the hand to heal and for Rio to even manage to whip out the gun let alone fire it with any speed or accuracy. He fesses up to Louisa that he’s not a secret Government agent, his usual cover story, but a bank robber and that the heirloom he gave her did not belong to his mother.

Bob gets fed up waiting, tries to pull off the bank job with one other accomplice, but the robbery goes wrong and a girl is killed. Ben pins the blame on Rio, arrests him and prepares to hang him. Louisa, who has initially rejected Rio after his confession and aware of his revenge plan, helps him escape.

The final shoot-out isn’t built up with the intensity of High Noon (1962) or Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) but with a resigned inevitability. Rio could have skipped out with Louisa and made a new life in Oregon. That would, in some senses, be revenge enough, stealing away the stepdaughter, one of the two main planks of Ben’s newfound respectability.

Don’t come here looking for honesty or upstanding individuals. Respectability is feigned – even Ben’s wife Maria (Katy Jurado) had a child out of wedlock. Everyone lies, even Maria – to protect Louisa from the stepdad’s wrath at losing her virginity.

In other words, a totally human cast of characters, shuffling the truth like it was a deck of cards. You wouldn’t trust any of them an inch. It doesn’t take much for cruelty to creep through the cracks, the cruel whipping, deputy Dedrick (Slim Pickens) handing out a beating to Rio in retaliation for being rejected by Louisa, Bob taking great delight in shooting dead an unarmed accomplice.

Ben isn’t alone about lying about the impossibility of coming to Rio’s aid, Bob does it too. Wife and stepdaughter lie to Ben. Ben lies to Rio. Rio lies to Louisa. Where this fits into one of Dante’s circles of Hell is anyone’s guess.

Cinematically, there’s only really one standout scene, when Ben calls out of hiding all the men who are going to surround Rio. But there are bold visuals. I thought I was watching a dud DVD because the image was so washed out for the opening sequences then I realized it was just the glare of the white desert sand and deliberate. And the backdrop of crashing waves suggests a different sensibility.

You can see the impact of Brando’s direction – he was making his directing debut – more with the leeway he allows actors to carry out little bits of business that only another actor would appreciate. A shoeless Ben dances over the hot sands, when he picks up the coins he has dropped he remains on the ground longer sifting through the sand in case he has missed one, Rio reacts to Dederick sweeping ash in his direction.

This is Marlon Brando (The Nightcomers, 1971) still in his pomp.

Written by Calder Willingham (The Graduate, 1967) and Guy Trosper (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, 1965) from the book by Charles Neider.

An exemplary work from a novice director.

Here yo go:

“Originally titled Guns Up, One-Eyed Jacks was based on Charles Neider’s 1956 novel, The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones. In an article he wrote for the 26 Mar 1961 NYT, producer Frank P. Rosenberg stated that he purchased screen rights to Neider’s novel in 1957 after having lunch with the novelist in Pacific Palisades, CA. The two agreed Marlon Brando would be the perfect leading man, but considered his casting unlikely due to Brando’s incredible popularity at the time. By Apr 1958, Rosenberg had commissioned a screenplay from Sam Peckinpah, and sent one of two copies to Brando, who responded with enthusiasm. As noted in the 24 Apr 1958 DV, Brando’s production company, Pennebaker, Inc., optioned rights to Neider’s novel and Peckinpah’s screenplay for $150,000. Rosenberg was brought on to produce, with Paramount Pictures set to finance and distribute the picture. Brando considered making his directorial debut with the project at that time, but decided to hire Stanley Kubrick instead, according to the 13 May 1958 DV.

Production was initially slated to begin in late Jun 1958, but the script was not completed in time. The 9 Jul 1958 DV noted that although the shoot was scheduled to begin in mid-Aug 1958, it would likely be further delayed. The project was still stalled when the 20 Nov 1958 DV announced that Stanley Kubrick had left the project to begin work on Lolita (1962, see entry). While the “official reason” given for Kubrick’s departure was a scheduling conflict, the 20 Nov 1958 NYT reported rumors that Kubrick and Brando parted ways over creative differences. Brando and actor Karl Malden were named as candidates for Kubrick’s replacement. A 20 Nov 1958 DV brief stated that Malden, who had been receiving a salary on the picture since 1 Sep 1958, declined an offer to direct, and the 21 Nov 1958 NYT confirmed that Brando had taken on the duty.

On 1 Aug 1958, DV announced that Brando was set to receive one-hundred percent of the film’s profits (in addition to a $150,000 salary) “in the only deal of its kind thus far.” In exchange for financing the entire budget, Paramount would own “distribution rights, amounting to around 27% of the gross.”

Rosenberg aided in the casting process by traveling to Mexico in search of unknown actresses for the role of “Louisa.” Pina Pellicer was ultimately chosen, and made her American film debut in the picture, as stated in the 15 Oct 1958 DV. According to the 12 Sep 1958 DV, actress Carol Leveque was tested for a leading role. An announcement in the 11 Dec 1958 DV listed Shichizo Takeda and Myoshi Jingu as recent additions to the cast, and the 1 and 10 Apr 1959 issues of DV noted that sixteen-year-old dancer Lolly Gohl and stuntman Jack Bellin would make their feature film acting debuts – with Bellin set to play the leader of a lynch mob. Chinese actress Lisa Lu was also cast as the “niece of a Chinese fisherman,” according to the 25 Aug 1959 LAT; however, Rosenberg’s 26 Mar 1961 NYT article indicated that Lu’s section of the film, “a transient love story between Brando and a Chinese girl,” was excised during post-production. According to an 11 May 1959 NYT article, Steven Marlo served as Marlon Brando’s stand-in.

Principal photography began on 2 Dec 1958, as stated in a 26 Dec 1958 DV production chart. Although Mexico was mentioned as a starting location in the 21 Nov 1958 NYT, filming commenced in the Northern CA towns of Monterey, Carmel, and Big Sur. The 22 Dec 1958 DV cited recent delays due to foggy weather, and reported that Brando had offered to fly cast and crew home for Christmas. On Monday, 5 Jan 1959, production moved to Paramount Pictures studios in Los Angeles, CA, where interiors were shot, according to the 2 Jan 1959 DV. When filming at Paramount was completed, desert exteriors were shot in Death Valley, CA. There, desert storms blew down some sets, the 20 Apr 1959 DV noted .

The original budget was cited as $1.8 million in the 20 Feb 1961 NYT. A protracted shooting schedule, caused by Brando’s exhaustive, improvisational directing style, upped production costs to an estimated $6 million. Initially scheduled for sixty days, the shoot ultimately lasted six months, according to Rosenberg’s account in the 26 Mar 1961 NYT.

A 24 May 1959 NYT article described the script as “rewritten beyond recognition” due to actors’ improvisations, and indicated that at least one of three screenwriters on set was regularly making complaints to the Writers Guild of America (WGA). In addition to improvisations, Brando used “tricks” to elicit performances, as noted in the 19 May 1960 LAT. In one instance, he secretly asked Karl Malden to fake a heart attack during a scene, and in another, he offered background actors prize money for the best reaction in a flogging scene. In a 27 Dec 1959 LAT interview, Brando expressed dissatisfaction with the cast’s acting abilities, stating, “Of my cast, Karl Malden, of course, knew all the mechanics of acting. Miriam Colon, too. But with the majority I had to be with them, on them, handling them all the time.” According to the 2 Apr 1959 DV, the production switched from a five-day schedule to a six-day schedule to complete shooting in time for Brando to begin work on The Fugitive Kind (1960, see entry). Brando was also reportedly living on the Paramount studios lot to save time. In the meantime, assistant director Francisco Day had to leave the project for a prior commitment to The Magnificent Seven (1960, see entry).

Problems that arose during filming included an injury endured by Brando during a jail escape scene, in which actor Slim Pickens accidentally struck Brando’s head too forcefully with a rifle butt, as noted in the 16 Jan 1959 LAT. Brando was treated with several stitches in his forehead, and only one side of his face was shot while the wound healed, according to the 20 Feb 1961 NYT. Another incident, in which Brando allegedly hit an unnamed actor too hard during a fight scene, prompted that actor to quit. He was replaced by an extra. The 26 Feb 1959 DV reported that Brando, whose “method acting” style entailed extreme absorption in his character, got actually drunk for one scene, and made actors Sam Gilman, Ben Johnson, and Larry Duran drink Old Crow bourbon for a “drunken card game scene.” The 4 Mar 1959 DV stated that Brando had recently “passed out” on the set and blamed exhaustion.

When filming was still underway, the 17 Mar 1959 LAT reported that Brando’s wife Anna Kashfi sued him for divorce on the grounds of cruelty, stating that Brando inflicted upon her “grievous mental suffering, distress and injury.” The 23 Apr 1959 LAT noted the divorce was finalized and Kashfi would be paid a settlement fee of $500,000.

Principal photography concluded on 2 Jun 1959, as stated in the 26 Mar 1961 NYT. Brando was said to have shot more “takes” than any director in Hollywood history, in an article in the 8 Nov 1959 LAT. Rosenberg claimed that over one million feet of film were exposed, and 250,000 feet were printed, as opposed to the average for a similarly budgeted picture: 150,000 feet exposed and 40,000 printed. The initial rough cut was around four hours and forty minutes long. Brando eventually decided to re-shoot the ending, and an additional day of filming took place in Monterey on 14 Oct 1960. The 17 Oct 1960 LAT noted that in the new ending, Pina Pellicer’s character, Louisa, lived instead of died.

The picture opened to mixed reviews on 30 Mar 1961 in New York City. Although the 15 Mar 1961 DV review predicted it would be a box-office success, an item in the 23 Oct 1961 LAT suggested it was unlikely the film would earn the necessary $13 million in ticket sales for Paramount to break even. Advance tickets were initially made available at Sun Ray Drug Stores, according to the 24 Mar 1961 DV; however, the 19 Apr 1961 Var indicated Paramount would likely cancel the promotion because it was causing confusion at oversold showings.

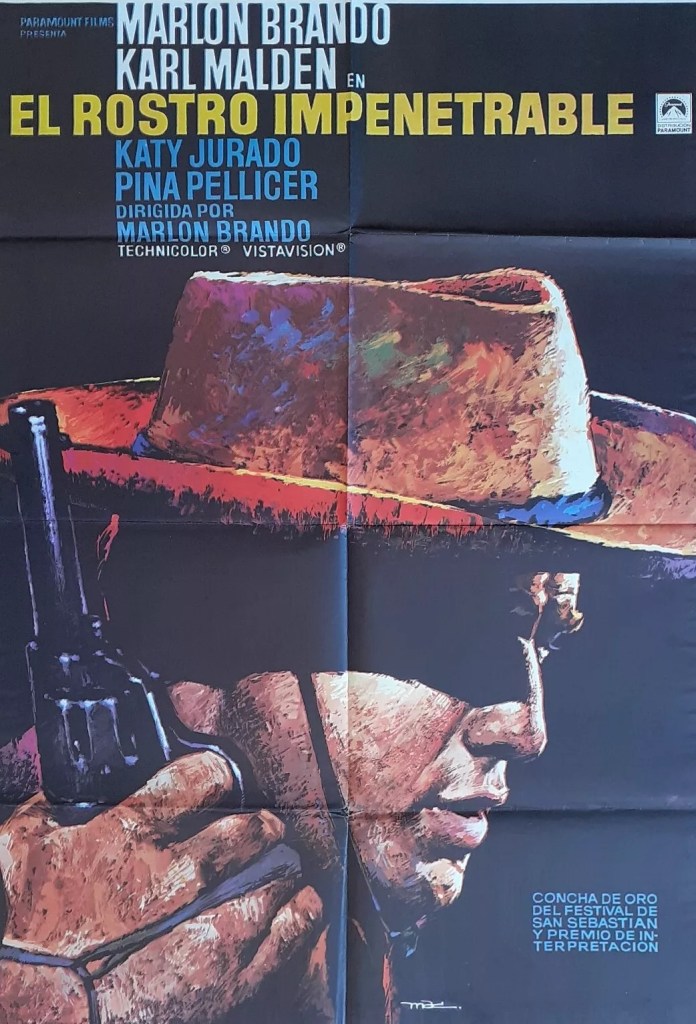

Charles Lang, Jr. was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Cinematography, and the film was awarded the Golden Seashell (Best Picture) at the San Sebastian Film Festival in Spain, as noted in a 19 Jul 1961 DV news item.

One-Eyed Jacks was the only motion picture directed by Marlon Brando, and the last film to be shot in VistaVision.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve got a Behind the Scenes all set.

LikeLike

Complements my piece today very well. Thanks.

LikeLike