Had this emanated from France or Italy or arrived bearing an arthouse imprimatur it might well have gained some critical traction. Not just because it is as far from the screen persona of star Steve Cochran (Mozambique, 1964) as you could get, but since this is largely a tale of loneliness and with some quite imaginative touches.

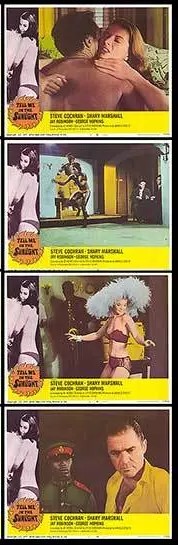

In a cramped apartment so small there’s nowhere to sit and eat Julie (Shary Marshall) sets out a picnic on the floor for merchant seaman Dave (Steve Cochran), the fare modest in the extreme, nothing more than heated-up soup from a tin. There’s an unlikely trigger point – a light switch that doesn’t work. In anticipation of Dave’s return, she not only bakes a “Welcome Home” cake but has painted on the walls an idyllic scene of the house she expects the couple to occupy.

But there’s a central issue. They’re both itinerants, Dave due to his job, and presumably not having an ounce of the settling-down bug, and Julie because she drifts from man to man, primarily out of necessity. She’s an exotic dancer and although she initially denies it – and he has to pretend to believe her in order to grease the wheels of incipient romance – she accepts financial favor from customers to the nightclub. In fact, she has a current boyfriend, Paul (Harry Franklin), a distinguished-looking doctor, an older man much fussed over by the club management due to the amount he spends.

The meet-cute’s been done before – they are both at the scene of an accident involving a young boy. They stroll away together. Their conversation is not intense, and the only way we realize that he has struck a spark is when she returns to her night-time gig sand is fined for arriving late. He watches her striptease act, and waits for her and they do some more strolling before returning to her flat, where she rustles up the picnic but before affairs can take a sexual turn she falls asleep in his arms.

This is very desultory stuff, no nudity or even obvious sex, and in the context of Hollywood output scarcely qualifying as a romantic drama, but place it in the European arthouse sphere and it proves much more rewarding from the very fact that nothing is overplayed. Little is even outwardly stated. Without a word suggesting this, both realize this is a chance to change random lives.

While there’s no commitment either side, when he leaves for a temporary job on another ship, he asks her to see him off on his midnight flight. That would mean her skipping a shift and to do so would risk being fired. At the last minute, she turns up. When she leaves as his plane is announced as imminently departing, he follows her for one last fleeting kiss and spots her outside in the arms of another man.

Unaware of this, she decorates her apartment in the manner described. He returns in a bad mood, gets drunk and on appearing at her apartment notices someone else must have fixed the light switch, tosses money on the floor and they make love as a financial transaction.

In the morning while she is distraught, he remains furious, scoffing at her painting on the wall and the cake. She explains that while the man at the airport was indeed her former lover Paul, he was only there in the capacity of a friend, who had driven her out, the only way she had of skipping out of the club and returning before being spotted and fined or dismissed. In any case she has been fired because the rejected Paul has abandoned the club and his absence has reduced the nightly take. And she paid for the light switch to be fixed.

Theoretically, in the hope of a happy ending, they reconcile. But a future together seems unlikely after the events of the previous night, which showed both in their true character, he as a paying customer, she as a paid sex worker. Neither show capacity for change, certainly not to find the kind of work that might bring marital stability.

Loneliness is the theme, how to cover up the cracks in fragile lives. In his job, women are non-existent, the only time he will meet one is on shore leave, and if he’s not shelling out for sex, he’s trying to pick up a vulnerable woman as is shown in the opening scene. As much as she needs extra dough to buffer her existence, she also needs someone to hold her at night.

This should have received some recognition at the time. Steve Cochran’s directorial debut was not accorded the same interest as other actors who had turned to direction such as Frank Sinatra (None but the Brave, 1965), Laurence Harvey (The Ceremony, 1963) or John Wayne (The Alamo, 1960). As an actor Cochran wasn’t on the critical radar, his tough guy roles hardly on a par with those of Humphrey Bogart or Richard Widmark who found greater fame.

However, the biggest obstacle to critical recognition was that Cochran died before they movie could be released and it took another two years before it hit movie screens by which time he was long forgotten.

Not only is the direction tone perfect but so is Cochran’s acting. Although strictly a B-movie actress, Shary Marshall (The Street Is My Beat, 1966) is very effective.

An unsentimental realistic drama that doesn’t fall into the traps of either into exploitation or melodrama

This is one of those forgotten pictures that is well worth a look.

One thought on “Tell Me in the Sunlight (1967) ****”