Not surprising since French critics worshipped Alfred Hitchcock – the only ones who gave him their wholesale approval in the 1960s – that a French director would attempt to pick up his mantle. But where Hitchcock majored on mystery and suspense and generally an innocent entrapped in conspiracy or crime, here director Claude Chabrol mostly dispenses with mystery concentrating instead on suspense. And it’s of the kind exhibited in To Catch a Thief (1955), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959) and Marnie (1964) where you are willing a character to get away with their crime or at least find redemption. And where Hitchcock places that load on the glamorous femme fatale, here Chabrol throws us into that most mundane of crimes, the jealous husband wanting revenge on his wife’s lover.

Successful businessman Charles (Michel Bouquet) should be enjoying life, glamorous trophy wife Helene (Stephane Audran) way out of his league, big house in the country, adorable son. But there’s something amiss. When his wife, who appears loving, makes sexual overtures in bed he turns over. He has grown suspicious of the amount of time she wife spends in Paris, ostensibly visiting her hairdresser or having beauty treatments or going to the cinema. Eventually, he hires a private detective and discovers his wife has a lover, Victor (Maurice Ronet). He decides to confront the lover rather than the wife. But instead of playing the outraged husband card, he pretends to be a man of the world, suggesting that Helene and he have an open marriage and that Victor is the latest in a long line of lovers. What he hopes to achieve from this is unclear, perhaps put Victor’s nose out of joint, perhaps cover up his own anger.

But it doesn’t go the way he planned. He spies an over-large cigarette lighter in the bedroom, a present he gave his wife for their third anniversary and kills Victor. This being the 1960s before forensics determined that you could never entirely eliminate a blood stain on a floor, Charles, with considerable diligence, cleans up the blood, remembering to wash out the bucket and cloth, wiping his fingerprints from everything he touched, bagging up the man in bed linen and dragging him out to his car.

On the way to disposing the body he is involved in a minor road accident. Police are called. He is saved from opening the car trunk because it is damaged. But when he tries to get rid of the body, the trunk proves impossible to open. Victor had appeared such a smarmy character, you’ve got no compunction about his death, you just want Charles to get away with the murder. Eventually, he forces the trunk open and drops the body in a small algae-covered pond. For a moment air trapped in the package makes it appear unsinkable. But, then – audience enjoying a sigh of relief and perhaps a homage to Psycho (1960) – it disappears.

Whether he revels in the discomfort of his wife who is no longer able to enjoy her twice-weekly assignations with Victor and unable, of course, to explain her bouts of distress to her husband and must keep up a façade, is unclear.

This is only a perfect crime to someone who has never been involved in crime, unaware of all the means of investigation at the disposal of Inspector Duval (Michel Duchaussoy) and his evil-eyed colleague Gobet (Guy Marley) who has the kind of look that says I know you’re guilty.

Turns out Helene’s name is in Victor’s address book and she can come up with no plausible reason for it being there. Charles denies ever having met Victor. The police are not convinced and return to interrogate the pair. Any viewer will quickly realize that it’s virtually impossible for either of the pair to remain undetected, the regularity of Helene’s visits can hardly have gone unnoticed, and even on a quiet street someone might have noticed Charles’s parked car and possibly him lifting the bulky package.

Nor does Charles dissolve in a bout of guilt. There’s an air of inevitability about him. You have no idea whether he might divorce Helene. The notion that she might not just take another lover doesn’t seem to occur to him and he’s not offered the opportunity to air his suspicions. Is he just going to bump off every lover his wife takes?

His wife finds a photograph of her lover in her husband’s pocket. But instead of denouncing him to the police, she burns it, either to protect her marriage or protect herself from the humiliation of being linked to the dead man, or because she has realized the folly of her betrayal.

We never find out her intentions because at that moment the police return and take Charles away.

A marvellous pivot on Hitchcock, with none of the B-film seediness that might have attended such a femme fatale, as Chabrol sets out his stall as a purveyor of the ordinary criminal, the one who didn’t run in high-class circles or was involved in international intrigue. The crime is so commonplace, that’s the beauty of it, and Charles such an ordinary character it all works superbly.

While Stephane Audran (Les Biches, 1968) is luminous, Michel Bouquet (The Road to Cornith, 1967) is her down-to-earth opposite. Written by the director and Sauro Scavolini (Any Gun Can Play, 1967).

A director finds his metier.

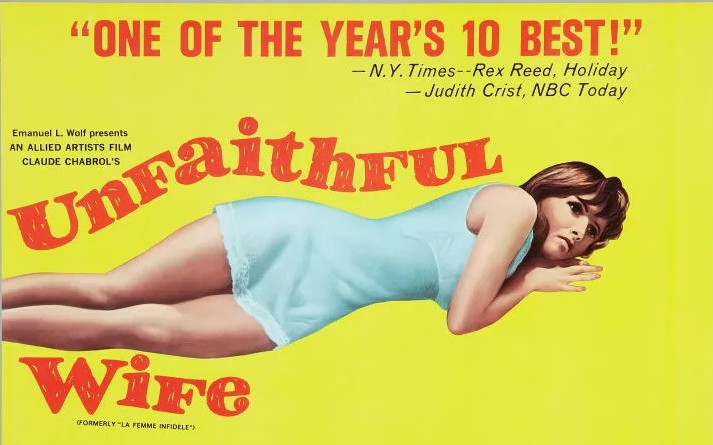

2 thoughts on “La Femme Infidele / Unfaithful Wife (1969) ****”