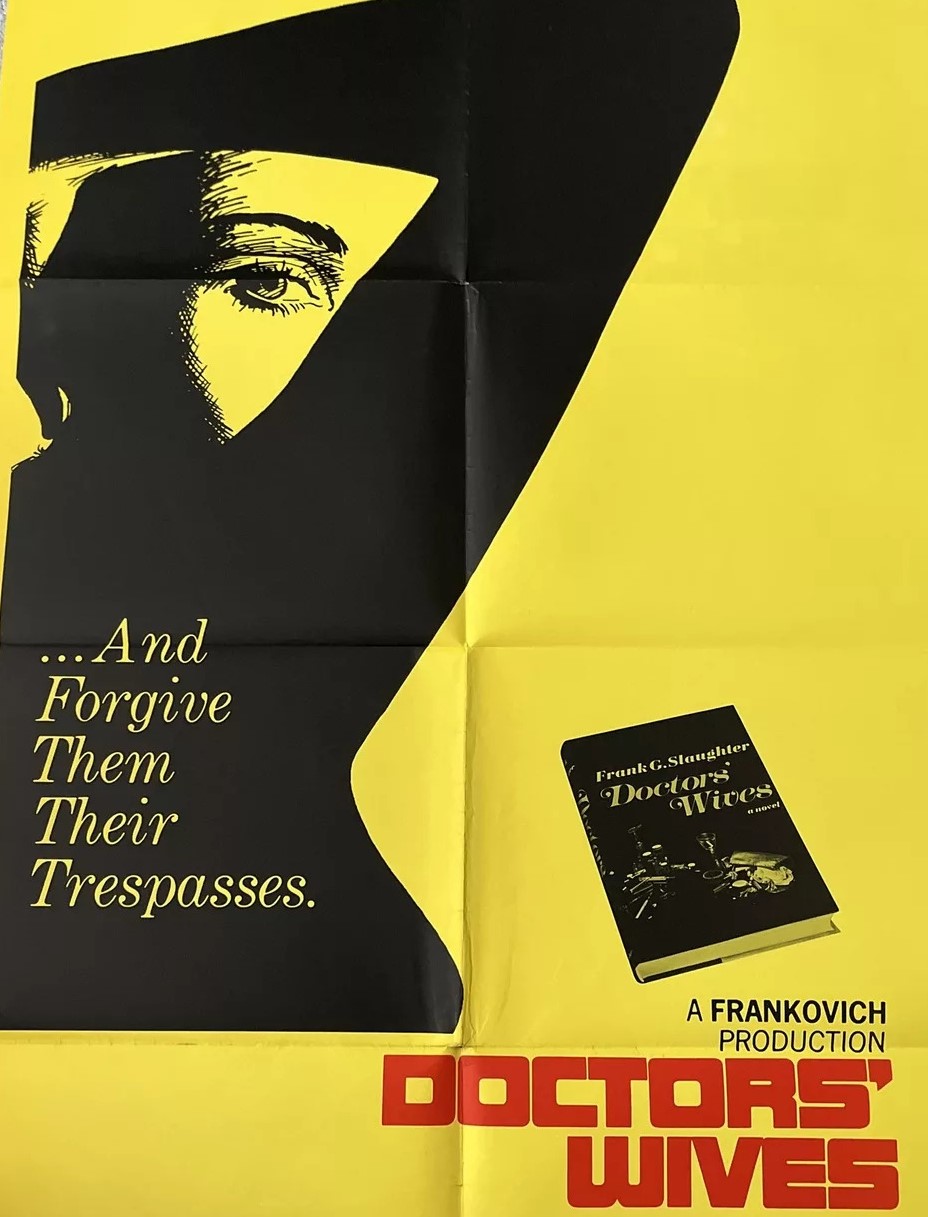

Five-star so-bad-it’s-good. Every now and then, especially approaching the annual touting of earnest films for Oscar consideration, we need reminded of just how good Hollywood is at producing hugely enjoyable baloney. Excepting the proliferation of recent MCU disasters, cinematic train wrecks don’t come along nearly often enough. Such botched jobs are always better if they are stuffed full of the worthy – Oscar recipients or nominees. Gene Hackman, Dyan Cannon, Rachel Roberts, Ralph Bellamy and screenwriter Daniel Taradash fulfil that requirement here.

A cross between Sex and the City and ER, with a third act that takes off like a rabbit desperately seizing on any convenient narrative hole. And a first act that pulls the old Psycho number of killing off the star before the picture really gets going. That old murder MacGuffin works every time.

“I’m horny” is about the third line in the movie, announced by sex-mad Lorrie (Dyan Cannon) to a tableful of over-refreshed doctors wives playing sedate poker in a country club at one table while at another table where you would expect the doctor husbands to be telling dirty jokes and whispering inuendoes they are boring each other with shop talk.

Unable to get the others to engage in revealing snippets about their sex lives, Lorrie rounds off the evening by informing the ladies that she plans to have sex with all their husbands to tell them where they are all going wrong, meanwhile gaily proclaiming she’s halfway there already. Which, of course, sets off a round of suspicion and accusations from wives to husbands.

Just to keep you straight on the who’s who: Lorrie is married to Dr Mort Dellman (John Colicos), Dr Peter Brennan (Richard Crenna) to Amy (Janice Rule), Dr Dave Randolph (Gene Hackman) to Della (Rachel Roberts), and Dr Paul McGill (George Gaymes) to Elaine (Marian McCargo) while Dr Joe Gray (Carroll O’Connor) and his ex- Maggie (Cara Williams) still hang around with the group.

As you might expect, every marriage is already in trouble, except, apparently, Lorrie’s because her husband, equally sex-mad Mort, appears to indulge his wife’s whims. Except, he’s not so easy-going, given he puts a bullet in her back when he discovers her making love to one of his colleagues.

Exactly which one remains a mystery for just long enough for the wives to rack up the suspicion level, and all the audience has to go on is the naked arm waving limply trapped under the naked dead weight of the corpse.

You might think, what with Dyan Cannon’s name being top-billed and she quite the rising star after an Oscar nomination for Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969), that we’re going to flip into a series of flashbacks to accord her more screen time. But, no, all we get is that opening risqué scene and her naked corpse.

Before ER’s creator Michael Crichton came calling a couple of decades later, the surgical profession was mostly represented in formulaic soap opera of the Dr Kildare small screen or The Interns (1962) big screen variety. But author Frank G. Slaughter, himself a practising physician, had made his name with a series of bestsellers that went into the intricacies of surgery and involved genuine medical jargon. So, before the identity of the illicit lover can be revealed, his life has got to be saved – after all he’s got a bullet in his heart. Cue even bloodier surgical shenanigans than kept fans of Mash (1970) hooked.

By the time we discover the victim was Dr McGill any chance of his wife stomping around in a huff at his infidelity is already off the menu because she’s been dallying with an intern.

I won’t go into all the all-round marital strife – triggered by alcoholism, drug addiction, infertility, ambition – that allows Oscar winners and nominees to try and act their way out of trouble because this picture has another absolute zinger to throw at you.

The murderer blackmails all four doctor pals for having a fling with his wife. To that cool $100,000 he adds quarter of a million from Lorrie’s wealthy dad Jake (Ralph Bellamy) for agreeing to make no claim on his wife’s estate. You kind of wonder what the heck use is all this dosh going to be in the slammer or Death Row. But that’s before you consider the zinger.

Mort’s a specialist and there happens to be a young patient desperate for his surgical skills. Young lad is son to head operating nurse Helen (Diana Sands) who is having an affair with Dr Brennan. So, a deal is done – you can’t wait for this humdinger, can you – wherein the D.A. is agreeable to release Mort from custody so he can perform this emergency operation while Dr Brennan and Jake – wait for it – agree to help him escape abroad.

As everyone knows you can’t tell one masked surgeon from another, so the first part of the plans works and while the cops keep a close eye on the fake Mort as he emerges from the operating theater the real Mort escapes in a parked car with the keys in the ignition. Except Jake isn’t quite a dumb or gullible as Dr Brennan and removes the keys so the killer can’t escape. Which was a shame because this picture could have gone on for another bonkers 20 minutes or so watching Mort outwit the cops.

As it is, there’s more than enough to fill in the time. Amy, something of a clothes horse with an extraordinary array of clothes and especially hats, goes all slinky in what looks like day-glo leggings to perform a bizarre seduction on her husband. Which elicits the movie’s best line, Nurse Helen complaining, “I don’t appreciate you sleeping with your wife.”

Unbeknownst to her, Lorrie has a female disciple who seduces every male in sight for research purposes, tape-recording every moment of the activity, so her victims are pretty much always in the coitus interruptus position.

And I can’t let you go without mentioning that Lorrie was also bisexual and counted among her conquests Della.

Except for the unlikely success of The French Connection later in the year which offered a different route in top-billing, Gene Hackman, had he continued taking on roles like this, might have ended up a perennial third potato. Bear in mind he already had two best supporting actor nominations in the bank when, third-billed, he took this on. Maybe he never read the whole script. Maybe this was the best offer going.

He’s not even the best thing in it. Too earnest for a start. Husband-and-wife murderer-victim tag team John Colicos (Anne of the Thousand Days, 1969) and Dyan Cannon take the honors. Directed by George Schaefer (Pendulum, 1969) and scripted by Daniel Taradash (Castle Keep, 1969). .

An absolute hoot.