As evidenced by its popularity in Italy often considered a forerunner of the giallo subgenre. While the involvement of Robert Bloch brings hints – mother-fixation, knife-wielding killer – of his masterpiece Psycho (1960), here some of those themes as reversed. And the stolid detective and younger buddy suggests the kind of pairing that would populate British television from The Sweeney (1975-1978) onwards. Surprising, then, with all these competing tones that it comes out as completely as the vision of director Freddie Francis (The Skull, 1965), especially his use of a rich color palette that would be the envy of Luchino Visconti (The Leopard, 1963).

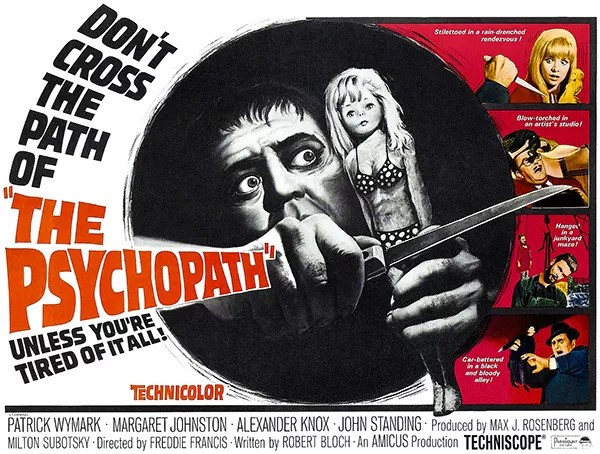

Theoretically mixing two genres, crime and horror, the resonance figures mostly towards the latter. Considering the crime element just for a moment, this features a serial killer, in the opposite of what we know as normal multiple murder convention, who leaves a memento at the scene of the crime rather than taking one away such as a lock of hair or something more intimate. Also, the list of suspects rapidly diminishes as they all turn into victims, still leaving, cleverly enough, a couple of contenders.

What’s most striking is the direction. Francis finds other ways rather than gore to disturb the viewer. The first death, a hit-and-run, focuses on the violin case, dropped by the victim, being crushed again and again under the wheels of the car. There’s a marvelous scene where a potential victim tumbles down a series of lifeboats.

The camera concentrates more on the villain’s armory than their impact: noose, knife, oxy-acetylene torch, jar of poison, the lifeboats, the aforementioned car. There are intriguing jump-cuts. We go from the smashed violin to a very active one, part of a string quartet. From toy dolls in rocking chair to skeletal sculpture. From a string of metal loops choking a victim to a man forking up spaghetti.

We go from the very conventional to the jarring, serene string quartet and loving daughter to wheelchair bound widow talking to the dolls, so real to her she shuts some naughty ones away in a cupboard. We move from one cripple to another, from real toys to human toys, to a human who talks like a wind-up toy.

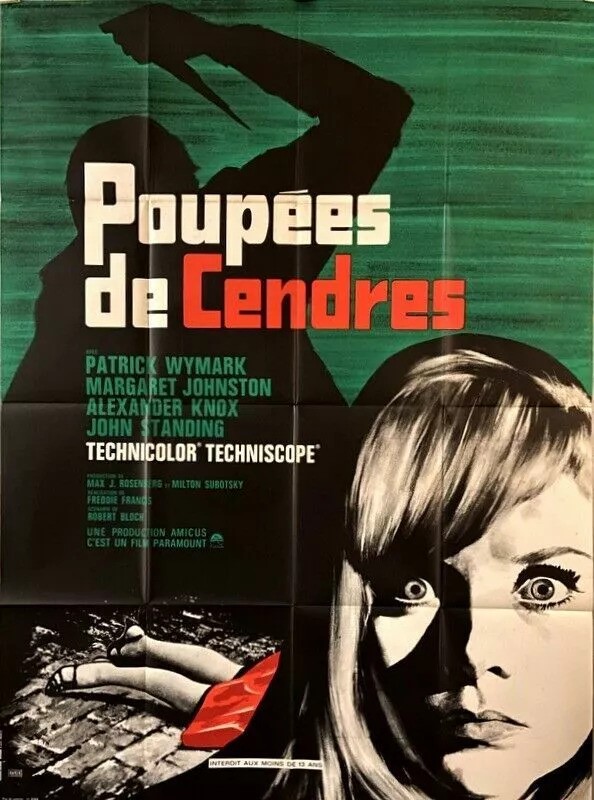

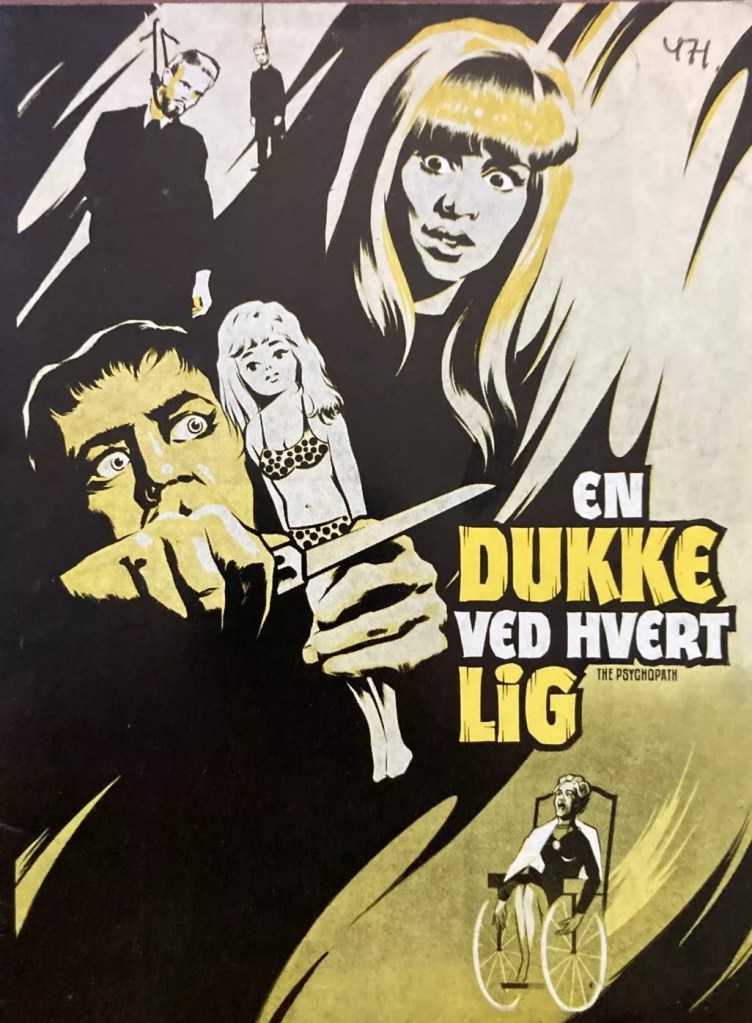

It soon occurs to our jaded jaundiced cop Inspector Holloway (Patrick Wymark) that the victims are connected, all members of the string quartet who were on a war crimes commission during the Second World War. At each murder the memento left, a doll with the face of the victim, leads the detective to investigate doll makers and then a doll collector, Mrs von Sturm (Margaret Johnson), widow of a man the commission condemned. Could it be the simplest motive of all – revenge? But why now?

The string quartet are an odd bunch, and on their own, you wouldn’t be surprised to find all of them capable of murder – sleazy sculptor Ledoux (Robert Crewdson) with naked women in his studio, the wealthy Dr Glyn (Colin Gordon) so weary of his patients he wished he’d become a plumber instead, the selfish over-protective father Saville (Alexander Knox) whose neediness prevents his daughter Louise (Judy Huxtable) marrying. Her American fiancé, Loftis (Don Borisenko), a trainee doctor, is also in the frame.

Mrs von Sturm could be the killer, her wheelchair a front – apparently housebound she manages a visit to Saville, though still in her chair. Her nervy son Mark (John Standing) also appears an odd fish.

As I mentioned, Holloway scarcely has to disturb his grey cells, the deaths of virtually all the suspects eventually make his job pretty darned easy. But Francis’s compositions let no one escape. Long shot is prime. Staircases fulfil visual purpose. The creepiness of the doll scenes wouldn’t be matched until Blade Runner (1982). Stunning twists at the end, and the last shot takes some beating.

Margaret Johnson (Night of the Eagle, 1962) is easily the standout, but she underplays to great effect. Patrick Wymark (The Skull, 1965) steps up to top-billing to act as the movie’s baffled center, with more of the cop’s general disaffection than was common at the time. Alexander Knox (Fraulein Doktor, 1969) knows his character is sufficiently malignant to equally underplay. The false notes are struck by Judy Huxtable (The Touchables, 1969) and Don Borisenko (Genghis Khan, 1964), both resolutely wooden.

Freddie Francis is on top form. Not quite in the league of The Skull. Commendably short, scarcely topping the 80-minute mark.

Well worth a look.

2 thoughts on “The Psychopath (1966) ****”