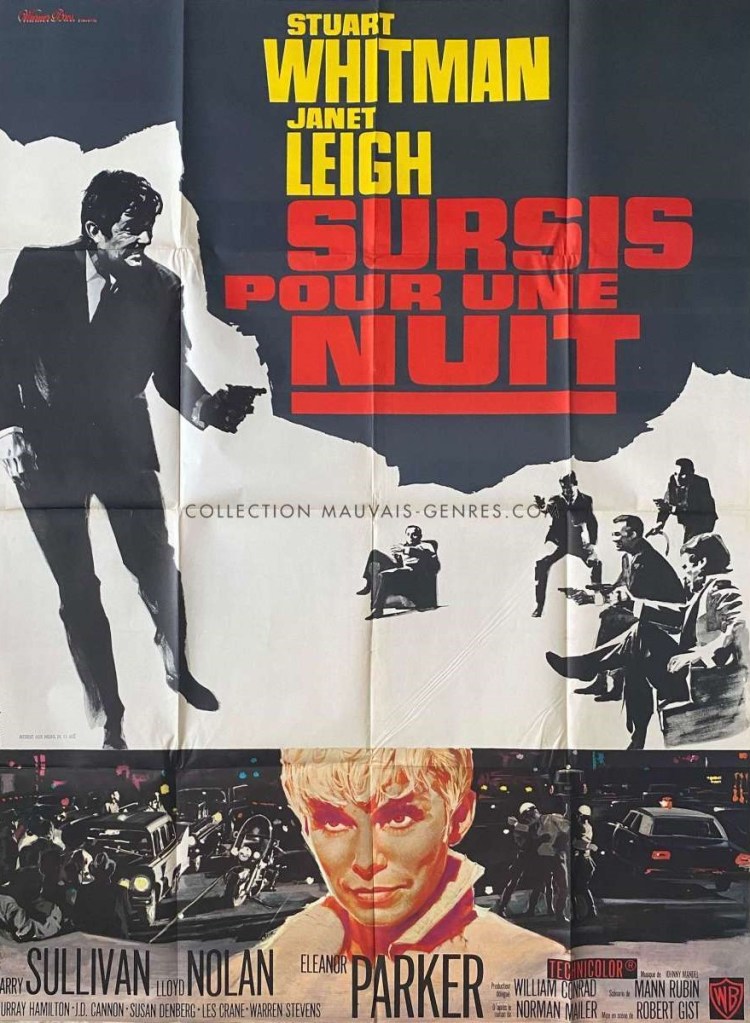

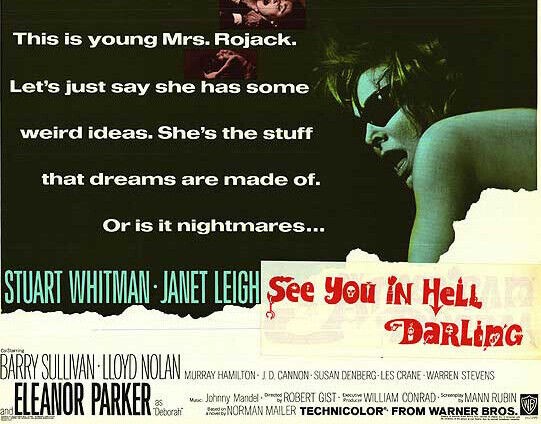

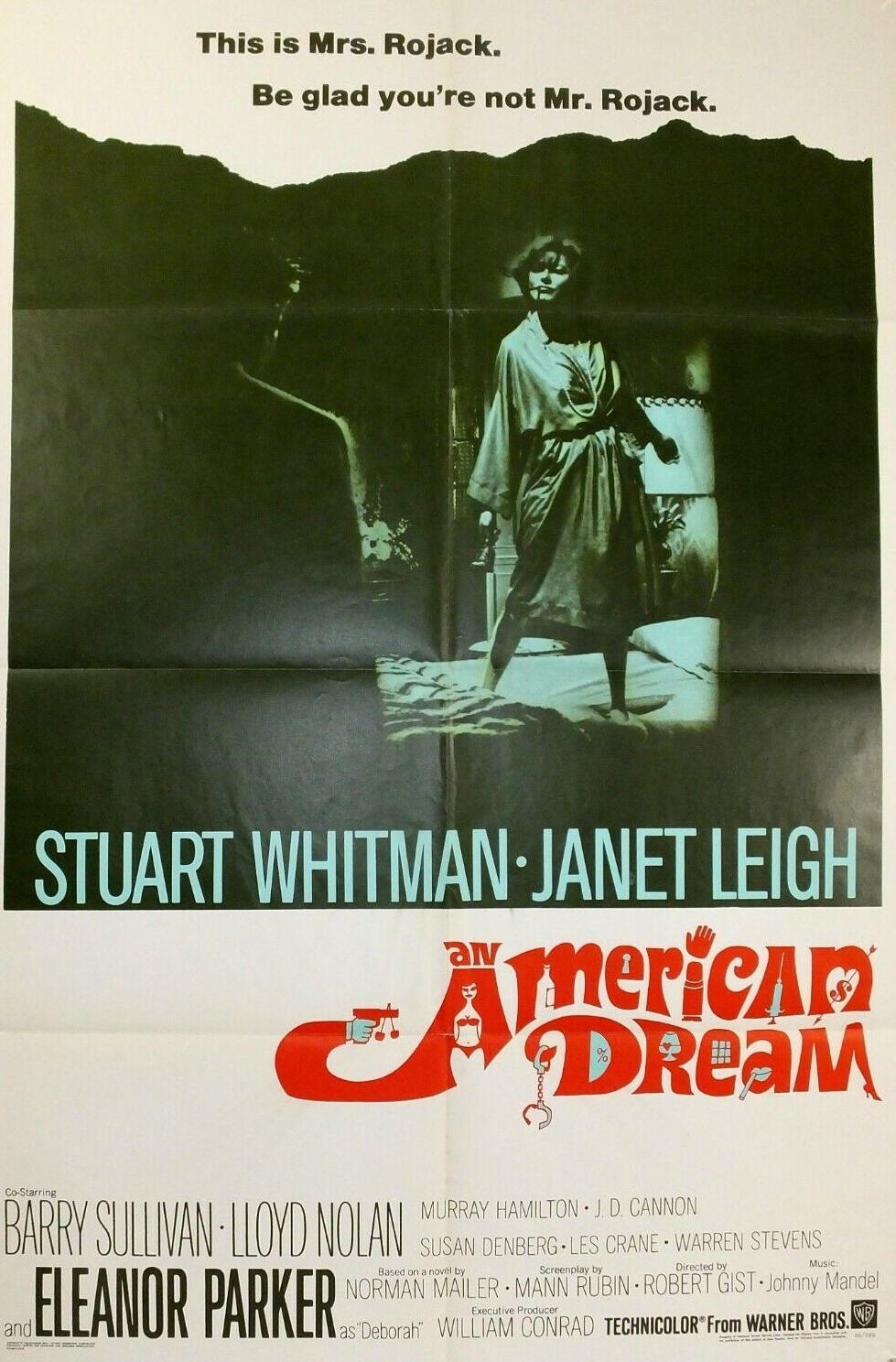

The Stuart Whitman Appreciation Society kicks into high gear with this under-rated drama. A huge flop and critically savaged at the time, its bitterly sardonic existentialist center will appeal more to contemporary audiences.

Norman Mailer, author of the source novel, was a hugely controversial public figure. A magnet for alimony, writer of sledgehammer prose, his filmed bestsellers (The Naked and the Dead, 1958) hit the box office with a heavy thud, climaxing in the disastrous Tough Guys Don’t Dance (1987). Politician, avant-garde film-maker (Maidstone, 1970) and leading exponent of the “new journalism” (The Armies of the Night, 1968), his works were exceptionally tricky to translate onto the screen.

This one picks its way through a flotilla of heavyweight themes – corruption, entitlement, the Mafia – by focusing on a trio of flawed characters dogged by ideals amd let down by reality. War hero crusading journalist and television’s version of a “shock jock”, Stephen Rojack (Stuart Whitman) is weary of beating his head against a legal brick wall in his bid to bring to justice Mafia lynchpin Ganucci (Joe de Santis). But he’s also extremely done in coping with adulterous alcoholic heiress wife Deborah (Eleanor Parker).

When he asks for a divorce she retaliates with violence and scathing verbal abuse. In the scuffle that follows she teeters off the ledge of their penthouse apartment. In his defence Stephen might well have claimed self-defence given she tried to crown him with a huge rock, or at the very least relief (although admittedly that has little legal standing), but instead opts for suicide. In revenge for Stephen’s ongoing slating of the police and because the deceased is daughter to exceptionally important entrepreneur Kelly (Lloyd Nolan), the eighth richest man in America, the cops try to pin on him a murder rap. The charge is really a moral one, and equally as ruinous to a fast-rising career, that while he may not have pushed her he didn’t act to save her.

As it happens, and apparently coincidentally, Ganucci happens to be passing the penthouse at the time the woman hits the deck. Equally, coincidentally, riding with him is his moll Cherry (Janet Leigh) a wannabe singer whose only gigs are in Mob-owned night clubs.

But Ganucci’s presence turns out not to be coincidental after all. He was on his way to straighten Stephen out, possibly intending to use blackmail since Cherry is a stain on Stephen’s supposedly unblemished past. The cops are ferocious in their grilling, and adopt an unusual amount of forensic evidence for the time. Stephen would probably have come apart quicker had it not been for rekindling romance with Cherry, which, unexpectedly, provides the hoods with a lure to reel him in.

The satire is mostly reined in – cops unable to catch the real murderous Mafia pick on the guy who’s picking on them, Stephen’s business partners latch on to his sudden publicity/ notoriety to negotiate a multi-million-dollar pay rise with, natch, a rider in the contract negating it should he be found guilty. The drama is characters racing headlong towards fleeting happiness, the tiny morsels of hope that might filter down from the unacheivable American dream.

The performances carry it. What was it in Stuart Whitman (Shock Treatment, 1964) that drew him towards characters given a hard time? Whatever it was, he rode it in spades and here he presents his most complex character to date, oozing suspicion, suffocated by guilt, believing that all will come right in the end if he has a good woman by his side, not realizing that Kelly knows only too well which side her bread is buttered on. Janet Leigh (Grand Slam, 1967) plays very much against type as the hard-eyed chanteuse but Eleanor Parker (Warning Shot, 1966) essays one of the best – and most vicious – drunks (and lost souls drowning in a sea of wealth) you will ever see.

Not to be outdone, director Robert Gist (Della, 1965), pulls off some neat scenes, opening with a shot of a naked Eleanor Parker clad only in dark sunglasses watching television, using camera movement to put claustophobic heat on Whitman during interrogation scenes (Christopher Nolan’s interrogator in Oppenheimer apes his trick of pushing his chair close to his victim), portraying the flimsy sexiness of Parker in flimsy negligee, all the time not letting Whitman escape from his internal demons.

Perhaps, more boldly, rather than, as would be the contemporary temptation, treating Deborah’s death as a mystery, the details only unfolding bit-by-bit and leading to a hairy climax, Gist shows her death and lets the audience make up its mind what part Stephen played in it. The downbeat ending, too, would sit more easily with the contemporary audience. Mann Rubin (The Warning Shot, 1967) knocked out the screenplay.

This finished off Whitman’s career – he didn’t make another movie for four years and then ended up in B-picture limbo, directors more interested in his square jaw than the inner confusion he was so deft at portraying.

Well worth a look.

Warning Shot 1967, sorry for the pedantry!

I do like ‘the flimsy sexiness of Parker in flimsy negligee’ has a certain bold poetry….

LikeLike

Corrections welcomed.

LikeLike