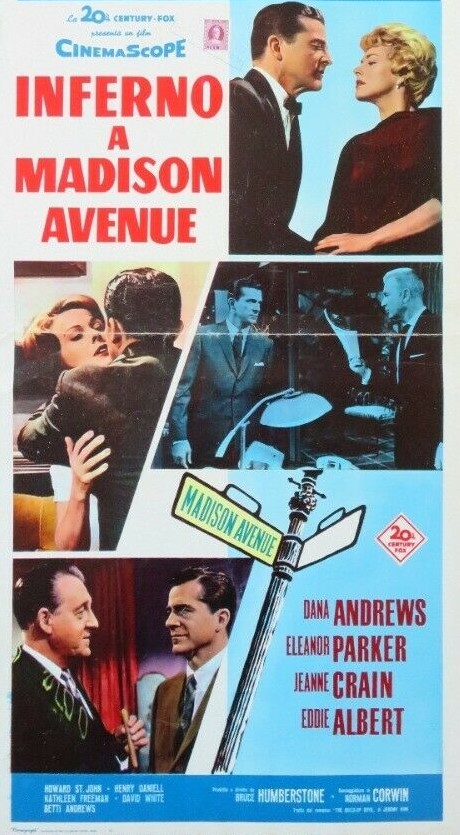

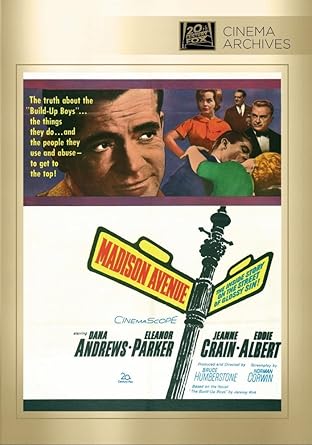

Surprisingly effective feminist angle. Unusual for the suave salesman to get his come-uppance from two vulnerable women, but that’s the case here, in an expose of the “build-up” (what we’d call “hype” these days) techniques of the public relations business, an area of advertising generally considered one step below the Mad Men of popular television. Fancy bars and cocktail dresses put in an appearance but, mostly, this deals with the grittier end.

This was pretty much the end of the mainstream Hollywood career for Dana Andrews. Still best-known for Laura (1944) and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) and for some key film noir titles, this was his last major top-billed role. He wouldn’t make another movie for four years and anyone coming to him in this decade would associate him with supporting roles in the likes of The Satan Bug (1965) and Battle of the Bulge (1965).

So this is, possibly unexpectedly, a performance to savor, for he is hardly the hero, more the kind of character who might turn up in a contemporary movie, with questionable motives to go along with his decided charm (look no further than Leonardo DiCaprio in Killers of the Flower Moon). Though hardly murderous, he is ruthless and doesn’t care who he brings down in achieving his objectives.

After losing his job for purportedly (an accusation unproven but going with the territory) trying to steal the major client, Associated Dairies, of his boss, J.D. (Howard St John), top executive Clint (Dana Andrews) plans to get his revenge in rather sneaky fashion, by turning round its poorly-performing subsidiary Cloverleaf. He targets the dowdy owner, Anne Tremain (Eleanor Parker), of its failing advertising firm, promising her client a big editorial splash in a big newspaper courtesy of journalist girlfriend Peggy (Jeanne Crain).

Anne’s the first beneficiary of his PR skills, reinventing her as a glamorous, power-dressing, more confident advocate of the persuasion industry. He inveigles himself into her arms, at the expense of Peggy. He aids the idiotic owner of Cloverleaf, Harvey (Eddie Albert), who spends all his time in the office playing with model airplanes. (From today’s perspective, he’s something of a savant, predicting these machines – think drones – could one day form part of the delivery contingent.)

To show just how damn clever he is, Clint “builds up” Harvey into the kind of self-made-man that has politicians purring, and brings Clint back into the winners circle. Unfortunately, the only way to get right in is through deviousness, a bit of back-stabbing here and there, dropping anyone who’s outlived their usefulness. But he’s not as clever as he thinks, lacks the business acumen of Anne, who’s denied him a share of her growing business, and therefore any real power base.

The women take unkindly to being used, Anne now the one doing the tossing-aside. For her revenge, Peggy writes an article that digs the dirt on him. Neither of these women would fall into the femme fatale category, though once all glammed-up Anne could pass for one had she required violence rather than business dexterity to exact her revenge.

Though both, unusually for the times, hold top positions in their businesses – Peggy’s a high-flying journalist working the Washington beat – they are presented initially as easy meat for a man capable of exploiting their vulnerabilities. Clint keeps Peggy on the back foot by failing to turn up for dates or presenting Anne as a rival for his affections.

This is an era where, purportedly, all women wanted was a ring on their finger, and to hang with being landed with an unsuitable man. But both Anne and Peggy upend that stereotype, seeing through the creature who’s come calling. In a western, audiences would have the satisfaction of seeing this kind of despicable character being shot. Here, they get to see him cringe, and be humiliated by women who have come to their senses. Albeit there’s a “happy” ending, that only occurs after some begging by the predator.

It suffers from too many long sequences, and by its determination to go down the satire route in exposing the seamier side of the public relations business. But there are some classic moments, such as when Harvey, tumbling through a prepared speech, has to suddenly wing it and finds his real voice.

But watching Anne get the measure of Clint and seeing him brought to heel by both women suggests the kind of ahead-of-its-time come-uppance that sets this up as an early feminist venture.

Eleanor Parker (The Sound of Music, 1965) and Jeanne Craine (Queen of the Nile, 1961) are both superb as women coming to their senses and this is a quite superb last top-billed hurrah from Dana Andrews. This was also the final outing for director H. Bruce Humberstone (Desert Song, 1953). Former newspaperman Norman Corwin (The Story of Ruth, 1960) and Richard P. Powell (Follow That Dream, 1962) based the screenplay on the best seller by Jeremy Kirk.

Resonates on the feminist front.

I’m still trying to figure out what ‘Do you always make love to a girl for business reasons?’ means. Is business the reason for always doing it? Is that worse than sometimes doing it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those Yanks! All mixed-up.

LikeLiked by 1 person