My discovery that Hayley Mills’ career could have taken an entirely different turn had either Deep Freeze Girls or When I Grow Rich entered production in 1965/1966 and therefore prevented the star returning to Britain for The Family Way (1966) – and, as it transpired, love and marriage – made me look again at the huge volume of movies that were either never made at the time initially announced or never made at all.

I’d covered a couple of classic examples previously, 40 Days of Musa Dagh for example taking nearly half a century from initial proposal to some kind of fruition. And, of course, the financial collapse of studios at the end of the 1960s put an end to the prospects of such big budget movies as Man’s Fate, to be directed by Fred Zinnemann.

But sometimes as many as half the movies announced by a studio or independent for their forthcoming schedule never made it to the big screen. Others such as This Property Is Condemned (1966), initially to star Elizabeth Taylor and directed by John Huston, still got over the line but with new players, Natalie Wood as star and Robert Mulligan in the hot seat. On the other hand, of the quartet of movies – Lie Down in Darkness, Guardians, Grass Lovers, and Linda – that producer William Frye (The Trouble with Angels) thought would make his name, none were made.

Everyone knows moviemaking is a dicey business, but you don’t realize just how tricky it is unless you count up just how many pictures, often trumpeted with big stars signed up, just don’t make it to the cinema screen. Not that Hollywood was unwilling to gamble. Studios snapped up anything – novel, Broadway play – that appeared a decent prospect.

In the early 1960s talent agency Famous Artists earned for its clients a grand total of $850,000 (equivalent to $8.5 million now) for a disparate bunch of properties. King Rat by James Clavell went for $160,000 plus a percentage and was made in double quick time. As was Lilith by J.R. Salamaca, costing $100,000, and Sylvia ($20,000 purchase price) by E.V. Cunningham (aka Howard Fast). Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest went for $85,000 to Kirk Douglas’s Bryna outfit, which explained why, a decade later, it ended up being produced by his son, Michael.

But Broadway play The Perfect Set-Up by Jack Sher, sold to Hollywood for $400,000 and with Angie Dickinson signed up for the lead, was never made. You might recall George Peppard in a TV movie Guilty or Innocent: The Sam Sheppard Murder Case (1975) but that wasn’t based on The Sheppard Murder Case by Paul Holmes that someone shelled out $25,000 for in 1962.

Director Paul Wendkos had planned to follow up Gidget Goes to Rome (1963) with Native Stone, an architectural drama in the vein of The Fountainhead based on the Edwin Gilbert book that cost him $10,000 but that hit the buffers. Two novels by thriller writer John D. MacDonald, hot after Cape Fear (1962) – the aforementioned Linda costing $15,000 and A Child Is Crying $5,000 – were not made either. Nor, out of this batch, were Indian Paint by Glenn Balch or Fish Story by Robert Carson.

Even as powerful a producer as Ross Hunter (Midnight Lace, 1960), couldn’t get onto the starting grid The Public Eye as a vehicle for Julie Andrews, Laurence Olivier and director Mike Nichols (it would have been his movie debut) – when made in 1972 starring Mia Farrow and Topol it was under the aegis of Hal Wallis. Hunter also spent $350,000 on Dark Angel to star Rock Hudson but that fell at the first hurdle as did Broadway play A Very Rich Woman to star Katharine Hepburn.

Tony Curtis was down for a remake of Casablanca (1942) called The Fifth Coin and relocated in Hong Kong and to co-star Nancy Kwan. Shooting on the Seven Arts production had a start date: November 15, 1965. But never went in front of the cameras. Kwan was particularly unlucky. The aforementioned Deep Freeze Girls also had a budget ($1.5 million) and a start date (October 1965) but it didn’t get off the ground either.

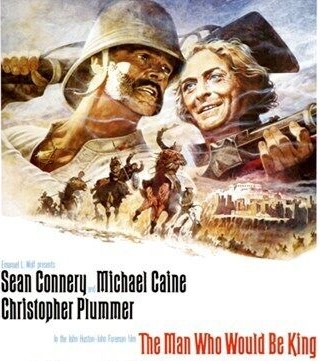

And of course Seven Arts had become enmeshed in the long-running John Huston saga of The Man Who Would Be King. This version, to star Richard Burton, had been set a $4 million budget and was due to start in April 1966. No go. At least The Owl and the Pussycat, budgeted then at $1.6 million and due to start on Dec 1965, was worth waiting five years for – when it was eventually filmed, though by Rastar not Seven Arts, it starred Barbra Streisand and George Segal.

In 1964 Columbia had 77 movies on the stocks. Richard Brooks was setting up Catch 22, Peter Sellers was being lined up for the musical Oliver!, and Carl Foreman was prepping Young Churchill. All these projects dropped off the roster, only to pop back up several years later with different stars (Ron Moody in Oliver!) or directors (Mike Nichols for Catch 22) or even studios (Paramount for Catch 22).

But others were simply shunted aside. Whatever happened to The Gay Place to team James Garner and Jean Seberg? Or The Fabulous Showman to be directed by Blake Edwards? Or another long-running saga, Andersonville with Stanley Kramer at the helm? Or Stephen Boyd as Richard the Lionheart? Even though The Ipcress File (1965) proved a big hit the same author’s Horse Under Water stalled at the starting gate, as did Robert Rossen’s Cocoa Beach and Ann-Margret in Strange Story.

When Robert Evans ushered in a new era at Paramount he placed his faith in writers. He doubled production and had over 40 writers working on projects. Some had little or no experience of movies but were big literary names. John Fowles, the adaptation of whose The Magus (1968) was an expensive flop, was hired to write Dr Cook’s Garden, but it was never made. Edna O’Brien had Three into Two Won’t Go on the stocks at Universal so she was set to write Homo Faber. Another casualty.

Oscar-winning screenwriter Edward Anhalt (Becket, 1964) was to make his directorial debut with We Only Kill Each Other. It didn’t happen. Nobody had ever managed to film Thomas Wolfe’s epic novel Look, Homeward Angel, so Paramount took a tilt at that without success. Escape from Colditz went into cold storage and an adaptation of Harold Robbins bestseller 79 Park Avenue ended up as a television mini series in 1977 and at a rival company, Universal.

It’s still standard operating procedure for Hollywood to snap up any big bestseller or Broadway hit without ever knowing whether it will ever see the light of day but willing to take the risk.

SOURCES: “Famous Artists,” Variety, August 8, 1962, p5; “Sanford and Frye of TV To Make Theatrical Films,” Box Office, January 7, 1963, p10; “Col-Frye TV Pact,” Box Office, August 19, 1963, p10; “Columbia Policy,” Variety, May 6, 1964, p13; “Seven Arts Pix Multiply,” Variety, March 31, 1965, p4; “Ross Hunter’s Crowded Future,” Variety, May 12, 1965, p7; “Bob Evans Pays Chip Service To Writer As Star,” Variety, May 1, 1968, p19.

I’m not coming back until you fix that rogue apostrophe in the first line! Hayley Mill’s!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have issued a stern warning to those aberrant apostrophes.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I take it Young Churchill became Young Winston for Foreman?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes.

LikeLike

Another winner Brian. DR.COOK’S GARDEN came out in 1971 starring Bing Crosby as a ABC Movie of the Week. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0065657/reference/

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank for that bit of info.

LikeLiked by 1 person