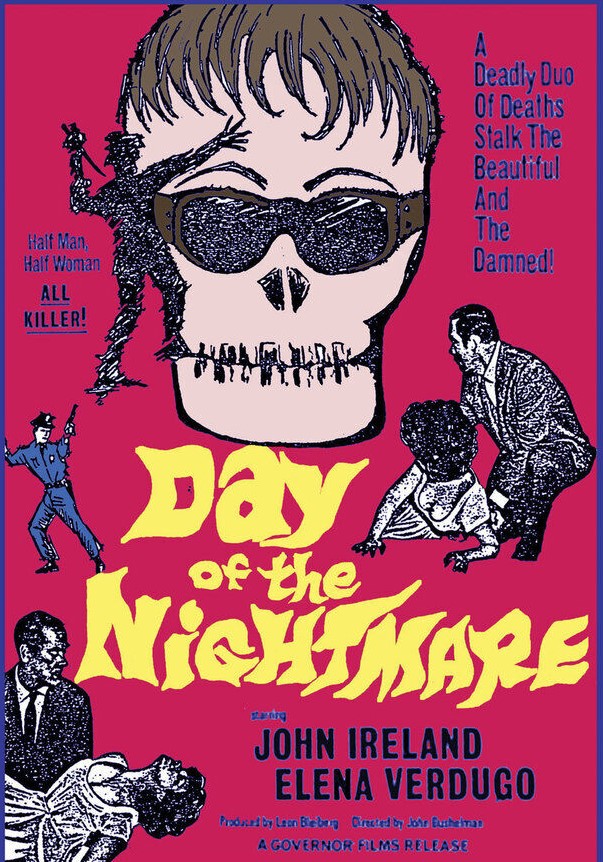

As you can imagine back in the day audiences struggled with accepting cross-dressing never mind transgender instinct – both deemed psychological aberrations – so it was understandable that the only treatment of the subject appeared in the sexploitation genre where budgets were so low a flop incurred no great financial loss. But even so, perhaps astonishingly so, despite a tendency towards violence, and what would amount to raw shocks, there was some implicit understanding of the need to shed one gender in order to take on the other.

More sympathetic in treatment than Homicidal (1961) but still from a narrative perspective taking the noir route, although, in reality, you could view the action as metaphor, hard-case chrysalis evolution.

Housewife Barbara (Beverly Bain) is being stalked by a blonde in a checked jacket and dark glasses, only saved from being slashed to pieces by unexpected appearance of a neighbour. Husband Jonathan (Cliff Fields), an illustrator, is often away to Los Angeles on business so she’s lonely and the marriage is under strain.

Meanwhile, Det Sgt Harmon (John Ireland) is investigating a potential murder. The tenant in the flat below heard a scuffle in the apartment above. But when the police arrive the only victim is a dog and, as we all know, it wasn’t a crime to kill a dog in the U.S. But someone else witnessed a trunk being dragged down the stairs from the apartment.

The trunk ends up in Barbara’s garage. Once the police start stitching clues together, the finger points at Jonathan. The dog was killed in his apartment (where he lives while working in L.A., home being too distant to commute) but his alibi stands up, and in the absence of a corpse it’s still no crime to kill a dog. But when Barbara opens the trunk with a screwdriver she doesn’t find a corpse, just drawings of a woman. Given that it’s Jonathan’s business to draw women she sees that as no big deal.

Jonathan’s father Dr Crane (John Hart), a psychiatrist, blames himself for his son’s marital problems, as it was his adultery that caused his own marriage break-up. Meanwhile, Barbara continues to be stalked, the killer getting a good deal closer. The cops feel Barbara is hiding something and if she is she doesn’t know what.

While she’s kept in suspense, the audience isn’t. Jonathan pulls on stockings and female apparel and kills his father. Once Barbara discovers her husband conversing with himself as both genders the game is soon up, but not before another terrifying chase.

Noir seems as good a genre as any for exploring the sexual psyche. That the misunderstood feel obliged to kill off anyone who knows them by their birth, rather than their desired, gender fits in with the notion often essential to noir of a criminal getting rid of traces of evidence. Given the era and the lack of gender exploration it would have been unfeasible to present a more sensible approach to the issue.

At the time I am guessing this was dismissed as sheer sexploitation. But, now, it appears to have considerably more depth. The afflicted repressed male with no way of expressing his female side coalesces with a movie maker with no way of tackling the subject in realistic fashion and so turns to the cliché of the person trying to start a new life by killing off all remnants of the old one. Although sold as a serial killer thriller, it’s nothing of the sort, Jonathan not on some sort of murderous spree as a result of repression.

As a bonus, there’s John Ireland (The Fall of the Roman Empire, 1964) and some humorous banter between the cops plus former B-picture star Elena Verdugo (How Sweet It Is, 1968), in her first movie in nearly a decade, as a boss.

Directed with some sensivity by John A. Bushelman (The Broken Land, 1962) from a screenplay by Leonard Goldstein in his only movie.

It’s definitely flawed, sexploitation is rarely anything else, but this falls on the right side of interesting. Viewed in a contemporary light, the sexploitation tag falls away, and it’s revealed as a more compassionate attempt to deal with what was then a taboo subject.