Marlon Brando’s box office cachet had crashed. He hadn’t made a picture in two years following the flop of Queimada/Burn (1969) which had followed his debilitating box office trend of most of the decade. While his stock remained high enough to headline such big budget numbers as The Chase (1966) and Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), thereafter confidence in his marquee value tumbled. Apart from Queimada, he had only been signed up for Night of the Following Day (1968), another loser.

But that last picture had brought him into the orbit of independent producer Elliott Kastner (Where Eagles Dare, 1968) who had been a friend of director Hubert Cornfield (Pressure Point, 1962) when they had both worked as agents at MCA. “Although he was crazy,” recalled Kastner, “I loved his writing and his drive.” Kastner was a fan of Cornfield’s earlier movies especially as they had been delivered on short time schedules. “I wanted to do something with Marlon Brando and he wrote Night of the Following Day.”

Brando still had clout in Hollywood. His three-picture deal with Universal obliged the studio to pony up for any (financially viable) projects he put to them. Kastner was delighted to hop over from his base in London to the French location and although the movie continued the actor’s poor reception at the box office, the producer enjoyed the experience.

Brando wasn’t averse to the “resting” that most actors endure, stints of unemployment between gigs. So when the actor approached Kastner to work with him again, it took the producer by surprise. “Marlon wanted to do a film,” said Kastner, “which was unusual for Marlon because he hides from work. He wanted to do a film in Europe and he loved staying at my house in the country. I talked to (Brando’s agent) Jay Kanter (who later became Kastner’s business partner) about it and we gave him a screenplay called The Nightcomers…that Michael Winner wanted to direct.”

Kastner had liked Winner’s output and was equally attracted to the fact that he also worked fast. Winner was contemptuous of directors who shot too much footage, especially “coverage”, filming a scene from too many different angles. But he was also a very fast editor. He took an editing caravan with him on location, and after the day’s filming ended at 6pm he spent the next two hours watching rushes and another two hours after that editing. His editor Freddie Wilson said,” His speed of decision in the cutting room saves a great deal of time and money.”

Winner had been sitting on the screenplay by Michael Hastings for some time. “No one was rushing to finance it,” remembered Winner, until Brando showed an interest. Winner arranged to meet the actor at his “modest Japanese-style house” in Los Angeles. However, insurance proved a sticking point following payouts for Quiemada.

“On a personal level,” recollected Kastner, “I thought he (Winner) was a bully with waiters. He was really nasty to people beneath him. I didn’t have much (personal) respect for him but he was very amusing.”

Due to scheduling conflict Vanessa Redgrave (Blow-Up, 1966) turned down the role of Miss Jessel. Winner also offered the part to Britt Ekland (The Double Man, 1967) provided she could bring some financing to the project. In the end, remembered Kastner, “Michael wanted to cast this girl with this big bust who was a halfway decent actor.” Neither Redgrave nor Ekland could compare in the bust measurement department to Stephanie Beacham, so clearly chest size was not a priority.

Kastner reckoned Brando “would bring plenty of poetry” to the project. It was remarkably cheap even for a star of Brando’s fading attraction. The budget was $686,000, of which Kastner received $50,000 as a producer’s fee plus 30% of the profits. Winner deferred his fee, only paid if the movie made money. At that point, Kastner was leading the way in finding funding outside the studio system. Funding for When Eight Bells Toll (1970), for example, was entirely sourced from an American businessman. For The Nightcomers, Kastner located investment of $100,000 from a company called Film & General Investments. Universal was involved through its contract with Brando – paying him his $300,000 salary for this picture to count as the final one on his contract, but declined to distribute the picture. For another producer, this might have been enough to kill off the project, but not for Kastner, who, following his current practice, intending to sell the completed film to a distributor.

As far as Kastner was concerned the movie went into immediate profit. Joe Levine of mini major Avco Embassy, still riding high after the success of The Graduate (1967) and The Lion in Winter (1968), ponied up $1 million for the worldwide rights plus a share of the profits. But Avco also limited its exposure, selling a 40% share to businessman Sigmond Summer for $1 million. (Judging from later legal documents, Universal retained some financial interest in the picture).

Brando had decided Quint was Irish. To learn the dialect, Brando and Winner got together with a group of Irishmen in the back room of a pub, one whom became the actor’s dialog coach on location.

The six-week shoot, on locations in Cambridgeshire, Britain, with Sawston Hall doubling as the mansion, began in January 1971. There was another reason for the speed of the shoot. Winner had contracted with United Artists to make Chato’s Land (1972) and there was no time to spare between the movies. Over 100 actresses auditioned for the role of the female orphan. Winner, seeking “someone over 18 who looked 11,” selected Verna Harvey (she also won a role in Chato’s Land).

Although Winner had gone to some expense to set up a private dining room for the star at Sawston Hall, Brando preferred to eat with the crew. According to Winner, despite Brando’s fearsome reputation, he knew all his lines, immensely patient with his young inexperienced co-stars, concerned about the crew, and, as importantly, arrived on time and even watched rushes, a rarity among the profession. Brando used earplugs to prevent distraction from extraneous noise. During the shoot Francis Ford Coppola flew over to spend time discussing the script of The Godfather with Brando.

Brando initially refused to have stills taken of him during the sex scene and only gave in after considerable persuasion, though he kept his wellington boots on. He wanted to leave the drunk soliloquy to the end of shooting. Though he was actually drunk after consuming a lot of Scotch, “he remembered his lines immaculately…(and) also matched his hand movements and body movements, which is very important in movies,” explained Winner, “because if you have to cut different bits of film together if the body or hands or arms are in a different position you’re in trouble.”

Jerry Fielding didn’t record his score until July during a three-day session with an orchestra of 80 at Cine Tele Sounds Studio. Despite his editing prowess, Winner realized his final version didn’t work. “The first cut was too fast. For a moody period film I’d just messed up. I put back seven minutes (of footage) and spent another three weeks getting it right.”

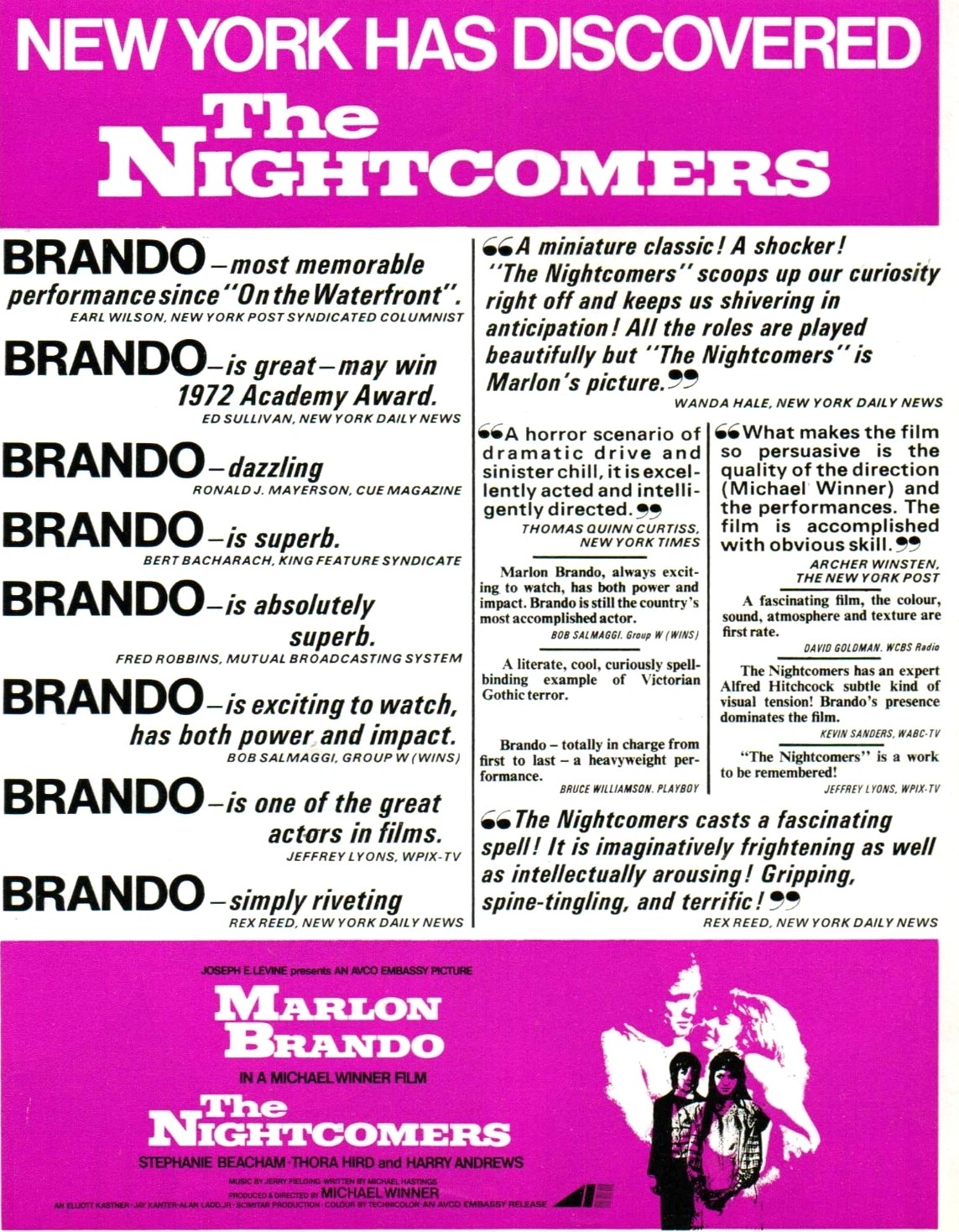

Thanks to its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival alongside the likes of Sunday, Bloody, Sunday (1971), it was touted, perhaps unwisely, as an arthouse picture, rather than majoring on the sex and violence. While Variety tabbed it a “grippingly atmospheric thriller,” only two out of the five most influential New York critics gave it the thumbs-up.

A distribution deal was not struck till the end of 1971. Rather than potentially riding along in the slipstream of The Godfather (1972), which was already attracting huge hype, Avco decided that it was better to come out before the Mafia picture than risk being swamped in its wake. But there was confidence in the project. “Joe Levine thought the film was so brilliant we didn’t have to wait for The Godfather,” related Winner.

It launched first in America, opening in February 1972 – beating The Godfather to the punch by a month – at the 430-seat Baronet arthouse in New York. The opening week of $20,700 was rated “nice” and held well for the second week before plummeting to $11,000 in the third week. It was yanked after six weeks.

By the time it spread out into the rest of the country, The Godfather rollercoaster was well into it stride, but the early release had not particularly gathered any pace and in the aftermath of the Coppola movie it was certainly buried. It opened to $6,500 in Boston compared to The Godfather’s second week of $140,000. There was a “scant” $39,000 from 13 houses in Los Angeles, a “modest” $4,000 in Louisville though $5,000 in San Francisco was rated “brisk” and the same amount in Washington “snappy.

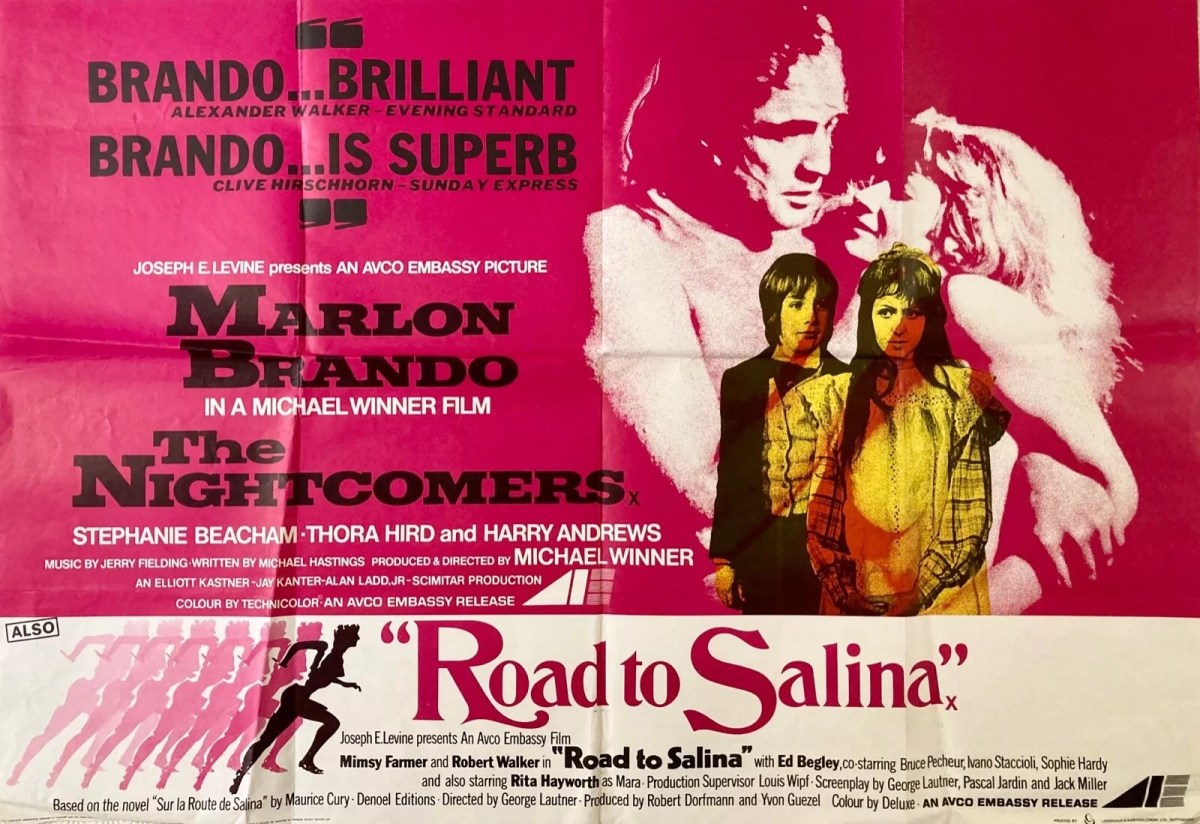

Initially, at least, Britain appeared more propitious. It opened in key West End venue the 1,400-seat Leicester Square Theatre to a “loud” $24,700 and though it dropped $10,100 in the second week, the third and fourth weeks improved on the second. Eight weeks into its West End run, when it was still pulling down $13,300, The Godfather put it to the sword with a record-breaking $191,000 from five West End houses. After that pummelling, The Nightcomers managed only three further weeks.

In fact, the movie did surprisingly well, especially overseas. Total rentals came to $1.69 million, a clear million-dollar profit on the negative cost. While less than half a million came from the U.S., and only $160,000 from Britain, the overseas market kicked in the bulk of revenue – $986,000 – possibly because it was released after The Godfather (1972) rather than, as in the UK and the US, before. In the run-up to and in the wake of The Missouri Breaks (1976), it was included in Brando perspectives at the Museum of Fine Arts, where it was presented as a “novel film…lost in the shadow of The Godfather,” and Carnegie Hall. But an attempt at commercial reissue proved disastrous – a “weak” $1200 in Pittsburgh.

Except from a financial perspective, Kastner wasn’t especially impressed, calling it “grim, boring, contemptuous of story, oblique.” Viewers, including me, beg to disagree.

SOURCES: Elliott Kastner’s Unpublished Memoirs, courtesy of Dillon Kastner; Elliott Kastner Archive, courtesy of Dillon Kastner; Michael Winner, Winner Takes All, (Robson Books, 2004); “Production Review,” Kine Weekly, January 23, 1971, p10; “Not So Young,” Kine Weekly, May 22, 1971, p16;“Jerry Fielding,” Kine Weekly, July 17, 1971, p10; “Michael Winner,” Kine Weekly, August 13, 1971, p10; “Nightcomers to Avemb,” Variety, January, 19,1972, p5; “New York Critics,” Variety, February 23, 1972, p35; “Picture Grosses”, Variety, 1972: February 23-April 26, June 7-14; July 19- Sep 27; “Broadway,” Box Office, February 9, 1976, pE2; “Museum of Fine Arts,” Box Office, October 18.