Reincarnation gets a bad rep. You could say the same for belief in angels. And of all the weird things to repurpose is the word “grapefruit.”

It used to be easy to define entries to the horror genre as old school (legacy creatures like vampires and werewolves and legacy situations like the old dark house and its modern equivalent). But now in addition we’ve had decades of torture porn, sexuality equating to grisly murder, and more recently high concept and arthouse. The latter two occasionally intertwine, which generally means slow-burn rather than shock jump.

Given Hollywood’s dependency on superheroes and their ever-increasing budgets, no surprise enterprising directors have been turning to the low-budget attractions of horror, where reduced cost equates to limited financial exposure, and creatives are given their head often to devastating effect – witness The Black Phone (2021), Smile (2022) and M3gan (2022).

But we’ve also been introduced to a new generation of sadistic villains, some who wreak havoc through the best of intentions, others, such as Heretic (2024) charmingly demented.

There’s been nobody quite as psychotic as award-winning counsellor Laura (Sally Hawkins) who’s in the kidnapping and fostering business for nefarious purpose. There’s no point trying to work out what’s going on in her head, though we are provided with enough tantalizing clues, because the only person it makes any sense to is Laura.

The title, unfortunately, gives too much away and you can guess from the outset that Laura is in the revival game. Her daughter has drowned and she seeks a replacement. Into her lap fall orphan brother-and-sister Andy (Billy Barratt) and Piper (Sora Wong) struggling to get over the gruesome death of their father.

While ostensibly bonding with the pair through a night of partying, in reality she’s setting up Andy for humiliation (she pours her own urine on him while he sleeps so she can accuse him of wetting the bed), disorientation (playing upon his fears) and ultimately turning his sister against him (Piper believes her brother whacked her in the eye while asleep) and if none of that works then just plain doing away with him. Piper is only partially sighted so her idea of what’s going on is restricted.

But while Andy wrestles with all this and visitations from his dead father, in the background is mute kid Oliver (Jonah Wren Philips) and with his every appearance he steals the show, and that’s despite a convincing performance by double Oscar-nominee Sally Hawkings (The Shape of Water, 2017).

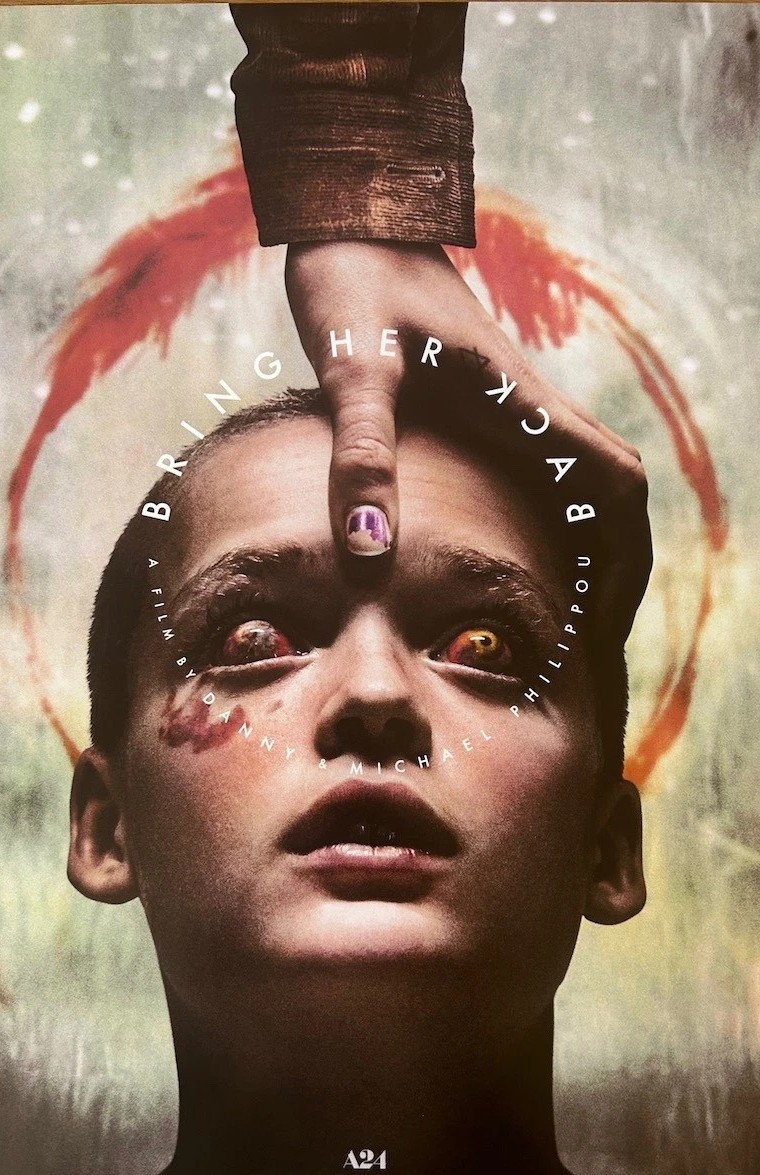

Shaven-headed, mute and locked in his room he resembles an angelic lost boy. But he’s starving and is apt at a moment’s notice to start chomping through wood or his own arm. He’s been fed some demonic nonsense and will not cross over the white painted circle surrounding the remote house. And when he can’t escape he turns turtle and has convulsions.

I’m not sure what rules surround kids in horror films and Jonah is way too young to be able to see the result but standing and crawling around drenched in blood with open scars and teeth missing I’m wondering just how he would be able to go to sleep at night (though, I guess he’s aware it’s prosthetic blood and obviously make-up completing the illusion). So the most demonic child since The Exorcist (1973) and it’s his image that will stick in your mind long after you’ve escaped the cinema.

There are plenty neat touches, the best being that Piper escapes a drowning by calling out “mom”, the title Laura has wanted to hear ever since her daughter passed away.

But slow-burn and certain arthouse aspects might put off the general horror fan.

Sally Hawkins and Jonah duke it out for most memorable turn and if you were going purely on the acting Sally would win, but movies are as much about the image as the word and on that score the boy wins hands down.

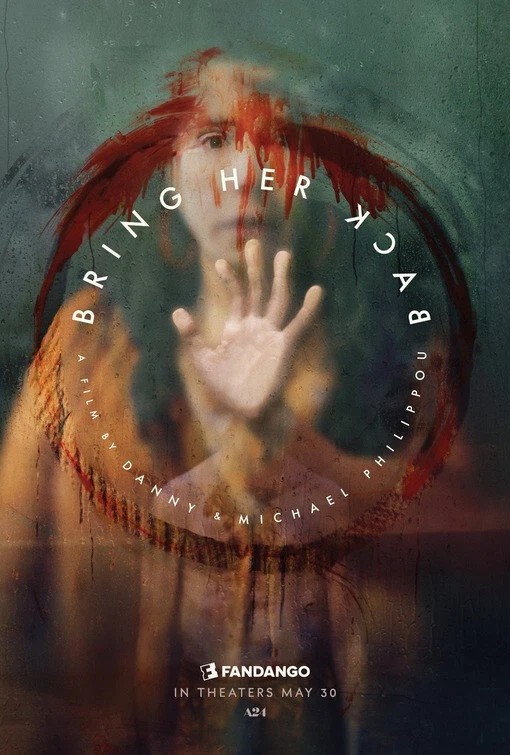

The Philippou twins, Danny and Michael, (Talk to Me, 2022) direct with the former responsible for the screenplay along with Bill Hinzman, his regular collaborator.