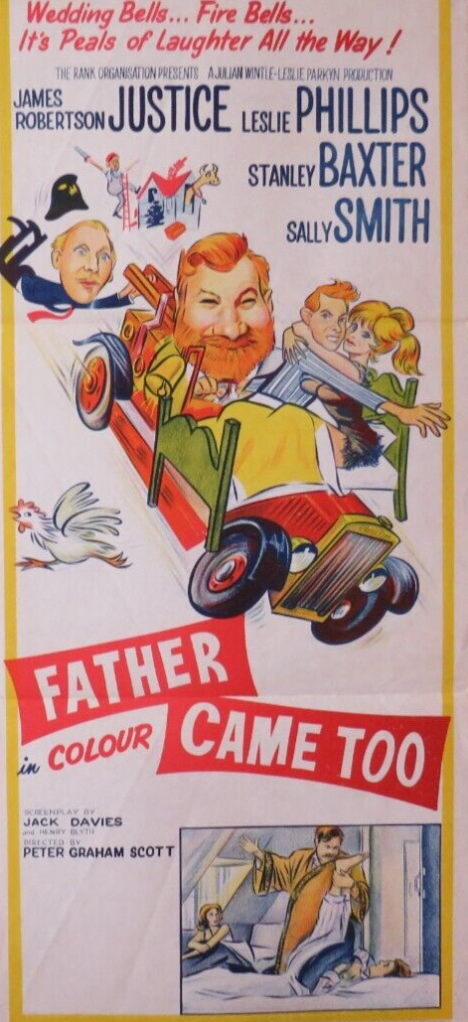

The gentlest of British comedies – a fading subgenre after the infiltration of the genre by the unsubtle Carry On pictures – that on the face of it appears a sequel to the very successful The Fast Lady (1962), featuring the same cast with the exception of Julie Christie. And with both Stanley Baxter (on television) and Leslie Phillips subsequently outpointing James Robertson Justice in the stardom stakes, contemporary audiences tend to come at this from a mistaken perspective.

James Robertson Justice was at the time very much a British institution and if not the star you cast him at your peril as he was likely to steal the picture from better-remembered actors such as Dirk Bogarde in the Doctor series, Margaret Rutherford in Murder, She Said (1961), David Niven in Guns of Darkness (1962) and Omar Sharif in Mayerling (1969). He was a big burly man with a bushy beard and a loud hectoring style, more Brian Blessed (Flash Gordon, 1960) than Robert Morley (Oscar Wilde, 1960).

He wasn’t the star of The Fast Lady and if it hadn’t been for the presence of Julie Christie (In Search of Gregory, 1969) he would have stolen that movie too. But when he was the denoted star, as here, the picture is built around him, so it’s not, actually, the tale of a young couple buying a money pit of a house, but of the male version of the interfering mother-in-law who makes their life merry hell.

Just married Dexter (Stanley Baxter) and Juliet (Sally Smith) purchase what appears an idyllic cottage in the countryside only to discover it requires a great deal of work. Renowned actor Sir Beverly Grant (James Robertson Justice) resents losing his daughter to a man he distrusts and to her moving out of his very grand home (named Elsinore, though I wonder how many viewers got that connection).

His attempts to take over the re-building programme are rebuffed by his son-in-law who hires the kind of builders, led by Josh (Ronnie Corbett), who give builders a bad name, tearing more tiles off the roof than they replace, creating more work for themselves or proving incompetent wherever they go. There’s a subplot involving real estate agent Roddy (Leslie Phillips), a budding thespian, desperate for the actor’s seal of approval.

But mostly, it’s everything going wrong and the father getting in the way and making things worse. But the tale doesn’t revolve around the hapless hero but around the domineering father and audiences back in the day would have recognized this, revelling in the father’s performance rather than trying to get on the side of the son-in-law.

Mostly, too, the comedic trick is slapstick, foot in paint pots, falling through floors, ceilings and roofs, an invasion of cows (one with the inevitable bonnet), being drenched by as much water as you could get on a set, and Dexter wringing his hands as the calamities – and the budget – mount.

Usually, the young couple taking on the world scenario just results in them encountering trouble from neighbors or various representations of authority and generally the focus from the outset is on them. But, here, it’s the opposite, audiences of the time waiting, not so much to see what new disaster will befall the couple, but to enjoy the carnage the father visits upon them. And viewed from that perspective it becomes far more enjoyable.

He’s far removed from the interfering mother-in-law cliché because that element of any comedy was usually a subplot played by a character actor who rarely evoked any audience sympathy. But audiences came to a James Robertson Justice picture to enjoy the mayhem he caused. He had screen charisma in spades, and especially when the screenplay was tilted in his favor, was apt to totally dominate a movie. And this is him at his best.

Stanley Baxter was somewhat miscast as a whiny incompetent husband – or, rather, he was not given a part which best utilized his uncanny skill for impersonation as later shown in his eponymous hugely successful television show. Leslie Phillips plays against type, more of an ingratiating Uriah Heep type than the uber-confident lady killer. Sally Smith (Naked You Die, 1968) hasn’t a hope of emulating Julie Christie. A slew of television comics – apart from Barker you can spot Terry Scott, Hugh Lloyd, Fred Emney and Kenneth Cope – put in an appearance.

Director Peter Graham Scott (Subterfuge, 1968) lacks prequel director Ken Annakin’s madcap zest but keeps it going none the less. Jack Davies (North Sea Hijack, 1980) and Henry Blyth (The Fast Lady) are as inventive as the idea permits.

Good old-fashioned fun but requires to be viewed from the correct character perspective.