As demonstrated in Madison Avenue (1961), the “big build-up” was code for inflicting on an unsuspecting public an unlikely candidate for acclaim. Of course, for decades, Hollywood hacks had been bombarding fan magazines, weeklies, glossy monthlies and dailies with beefcake and cheesecake photos of promising new talent. But the hook was that these actors were shortly appearing, albeit in a bit part, in a few months’ time in a forthcoming movie.

Modelling was another device to attract the attention necessary to generate a screen career. Sometimes, these (predominantly female) models would be making their first throw of the dice, hoping that some producer in an idle moment might catch a glimpse. Or, they could be women who made a living from selling such snaps to such media.

But, usually, it was one thing or the other: gratis photos handed out by grateful studio marketing teams or photos that an editor paid for in the hope they would increase circulation (in the days when there was no such thing as a giveaway magazine). La Welch appears to have fallen into the latter category.

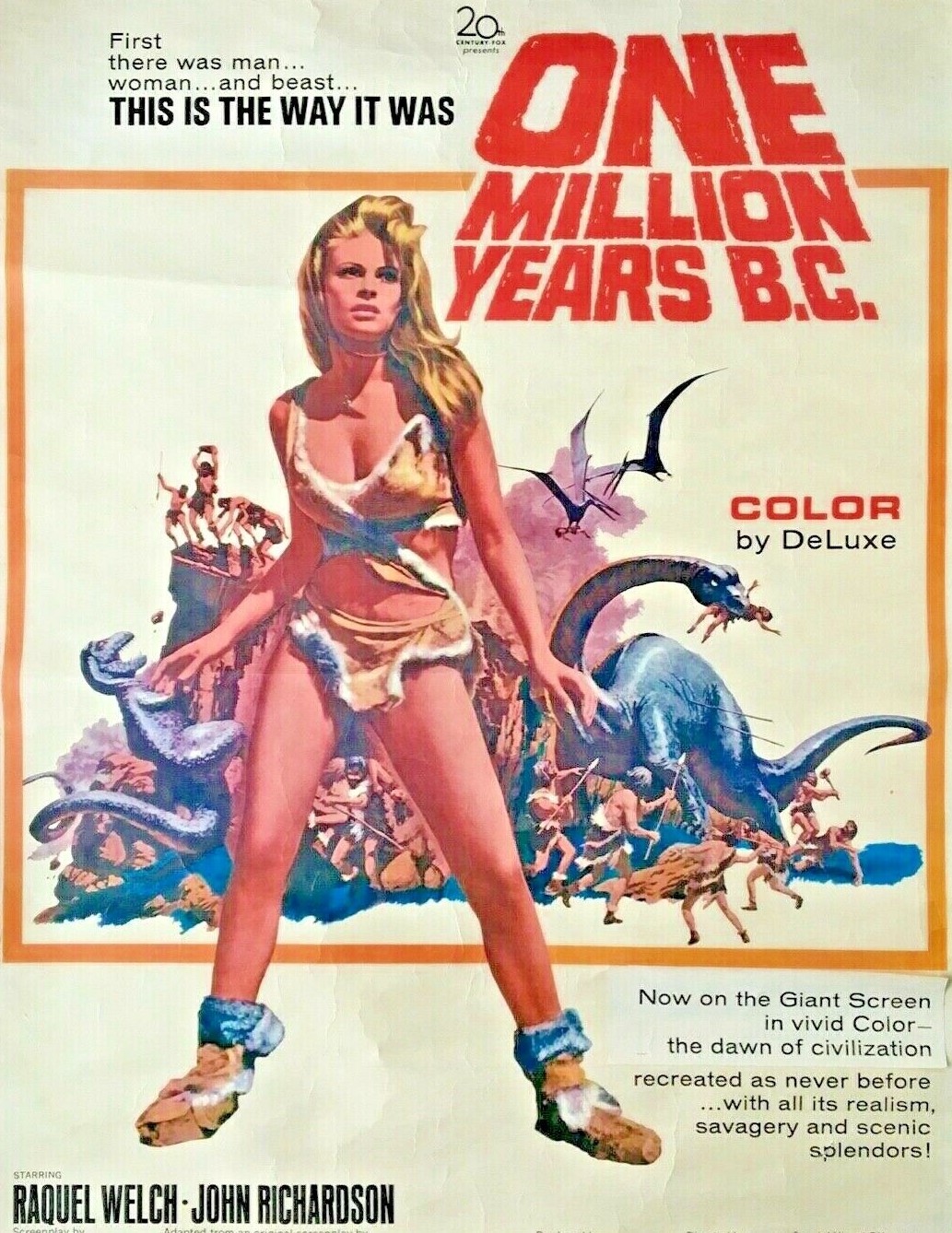

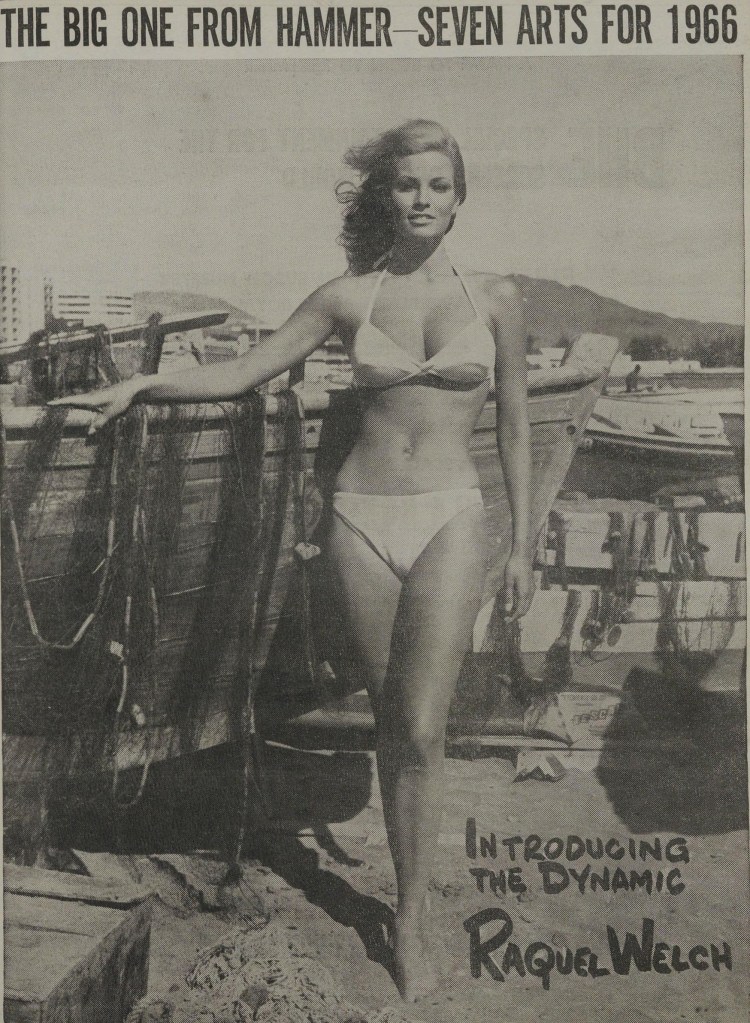

But it was a heck of a long-term build-up given that with the exception of the virtually unseen Swingin’ Summer (1965), in which she has a bit part, Raquel Welch did not appear in a movie until September 1966. By that point, modelling a skintight number in Fantastic Voyage – it was December before that iconic fur bikini in One Million Years B.C. set male hearts pumping – it seems that magazine editors the world over were prone to giving her space in the years prior covering 1964-1966 when she was effectively an unknown.

Which would go some way to explaining why by the time her first movies hit the screen she was already a familiar face (and body, it has to be said) to many (and not exclusively male) in the audience. The promotional push was supplied by Twentieth Century Fox which had signed her to a five-picture contract, making her, perhaps in their own words, one of the most sought-after actresses in Hollywood.

But deals with studios for new talent were ten a penny, no guarantee the studio would keep its side of the bargain, nor that the contract would run to term, nor that the actress would be handed anything but bit parts. Still, it probably cost relatively little to start pumping out promotional photos with “new rising talent” as the lure. Magazines seemed happy to accept on face value that she was a rising star even though there was no proof that she had the talent to match.

Life magazine proved something of a stepping stone. She was featured in a bikini in its Oct 2, 1964, issue. But you could just as easily have caught her in a leopard-skin dress draped across a cocktail stool, one of several cheesecake pictures taken to promote the starlet. Parade magazine, in Britain, something of a lower-grade male magazine, far removed from the likes of the glossier Playboy, was among the first to take the bait, in December 1964 (see above) handing the young potential star its front cover. (Her surname was misspelled as Welsh – and her Christian name was misspelled as Rachel when she featured again in March 13, 1965.)

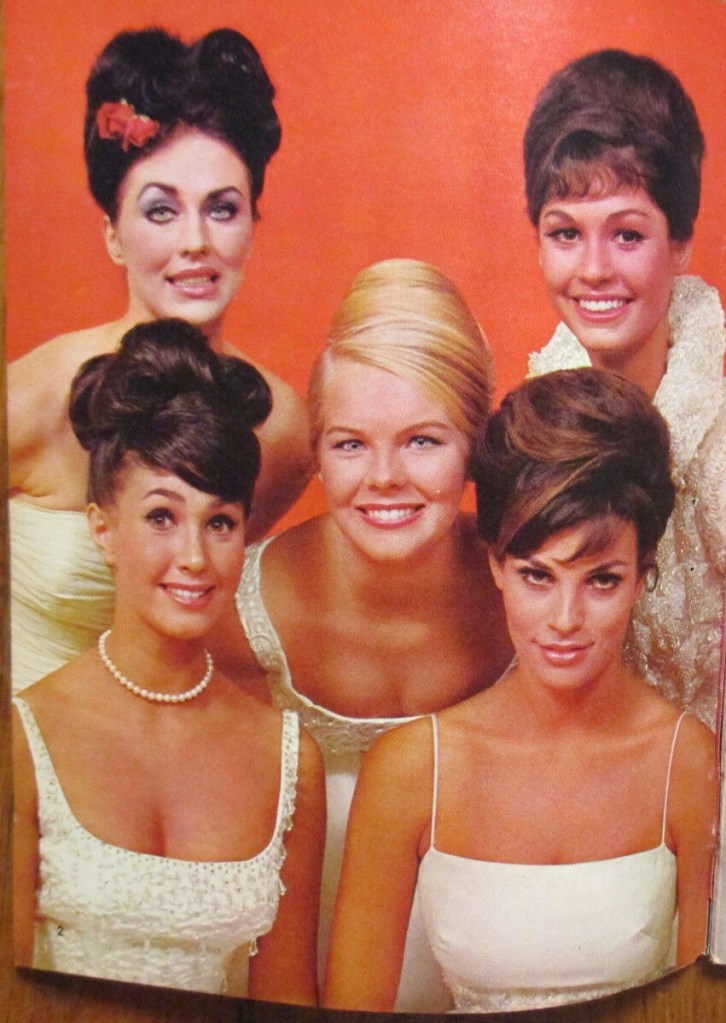

Five of the 10 chosen Deb Stars of Tomorrow. See if you can spot our gal.

But the real boost came at the end of December 1964. That month she was one of ten potential female stars featured in the Dec 27 issue of New York Journal-American under the title “TV’s Magic Wand Taps Girls As Stars of Tomorrow.” She had been chosen to appear on ABC TV’s “Debs Stars of 1965” programme. This show claimed an 85 per cent success rate in picking potential stars, with Kim Novak, Tuesday Weld and Yvette Mimieux among previous winners.*

In April 1965, the distinctly more upmarket – and not male-appealing – McCalls in the U.S. came calling, but that front cover dispensed with the sexy look, presenting her wearing spectacles. By September 1965, the Fox marketeers had been hard at work and won for her – a full year before Fantastic Voyage opened – the front cover and an inside spread in the British edition of movie fan magazine Photoplay. The next month brought another iconic photograph, the “nude” spread in U.S. upmarket monthly Esquire, accompanied by a full-page interview that treated her as the next big thing, again on the word of Fox, nobody having as yet seen so much as an inch of the footage of the sci-fi picture.

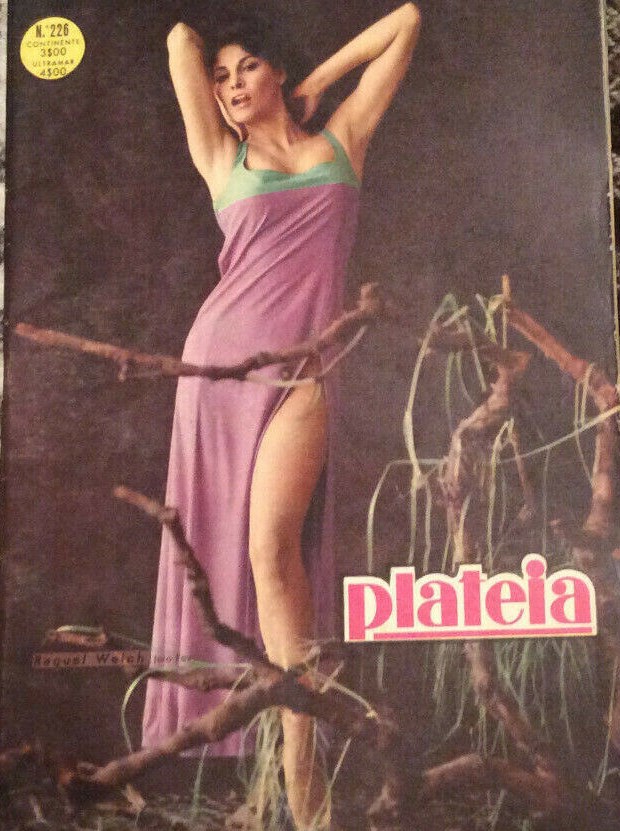

The same month in trademark bikini she was on the front cover of U.S. Camera and Travel magazine (surname again misspelled), photographed by Don Ornitz and described as “a rising young actress with many screen and TV credits to her name” without specifying that in fact these were mostly uncredited or in bit parts. Also during 1965 she featured in Turkish magazine SES and Portuguese magazine Plateia.

But there was also the grind. She advertised Wate-On slimming in Screen Stories in 1965, was the cover model for True Love in September 1965 while for Midnight magazine – and surely this was a story dreamed up by a publicity hound – her front cover picture was accompanied by the heading “Adultery Can Save Your Marriage” and inside she was quoted as saying “A Wife Should Let Her Husband Cheat.”

The big build-up went into overdrive in 1966. She modelled bikinis in two more front covers in Parade (all name errors corrected) in January and July. Australians preferred a more demure – or at least non-bikini – look. In Australian Post (June front cover) she was photographed wearing a “dress of ten thousand beads” from her unnamed next picture (neither Fantastic Voyage nor One Million Years B.C. obviously). There was a slinky pink number for the Australian edition of Photoplay (August, front cover and full-page photo inside) and a quote “I think its important for a girl to exploit her physical attractions – but with restraint.”

She also graced Hungarian magazine Filmvilag and Showtime, both in August. Perhaps the most prescient feature ran in Woman’s Mirror in April 1966. For once she was not granted the cover, but featured on a two-page spread inside under the heading “A Star Nobody Has Seen But Everybody Is Looking For.”

Most of her figure was hidden on the front cover of Pageant (July). SES had something of a scoop in its April edition with some behind-the-scenes photos of Welch in her fur bikini for One Million Years B.C. and she made the cover of German magazine Bunte (June).

Exactly how busy and successful Welch – and her promoters – had been could be gauged from the photo that appeared in the Aug 26, 1966, issue of Life, in which she was pictured in front of a wall of over 40 of front covers she had adorned in the previous two years. Pictorial proof that she was in demand and that magazine editors, long before the public had the chance to witness her screen performance, could recognize a certain kind of charisma. (She was featured in Life again in Dec 1966, in a bikini, but seen sideways, bent over and with her hair in pigtails – and on the cover of its Spanish edition on Nov 21.)

And there was another kind of accolade coming her way in Britain. She was chosen as the first cover model for the first issue of men’s magazine Mayfair in August 1966, the same month as she was positioned in the same prominent spot on Adam, another men’s magazine, and in the more sedate British magazine Weekend, in which she was promoting Fantastic Voyage.

But she would soon be forever associated with the fur bikini, posters of which were soon plastered over the walls of teenage boys. The fur bikini more than anything else broke the mold in the presentation of a new star, and luckily for Welch, the ground work had been done courtesy of the long-range big build-up.

*The other nine Deb Stars of Tomorrow were Barbara Parkins (Valley of the Dolls, 1967), Mary Ann Mobley (Istanbul Express, 1968), Margaret Mason (no movies but some television), Wendy Stuart (couple of bit parts), Beverley Washburn (Pit Stop, 1969), Tracy McHale (nothing), Laurie Sibbald ( a few television episodes), Janet Landgard (The Swimmer, 1968) and Donna Loren (a few television episodes). No prizes for guessing who won that particular Deb Star competition.