Last hurrahs are rarely as sweet. But I’m beginning to wonder if the Warner Brothers very restricted U.S. domestic release isn’t a clever publicity ploy. You know the kind, attract the ire of critics who like nothing better than painting studios in a bad light and hope for a tsunami of social media outpourings. It’s now beginning to look more like a standard platform release, the kind employed to win Oscar favor.

Directors are often declared geniuses because they have a particular facility with visuals, can use the sweep of the camera or a particularly vivid composition, tackle controversial subjects, or build up a distinctive oeuver by returning again and again to a theme or genre. This is well outside Clint Eastwood’s comfort zone. For a start he’s not acting in it, it’s not a western and it doesn’t concern on-screen violence of any kind. His most common screen persona was of the man with a past trying to live a quiet life who is roused into anger and violence.

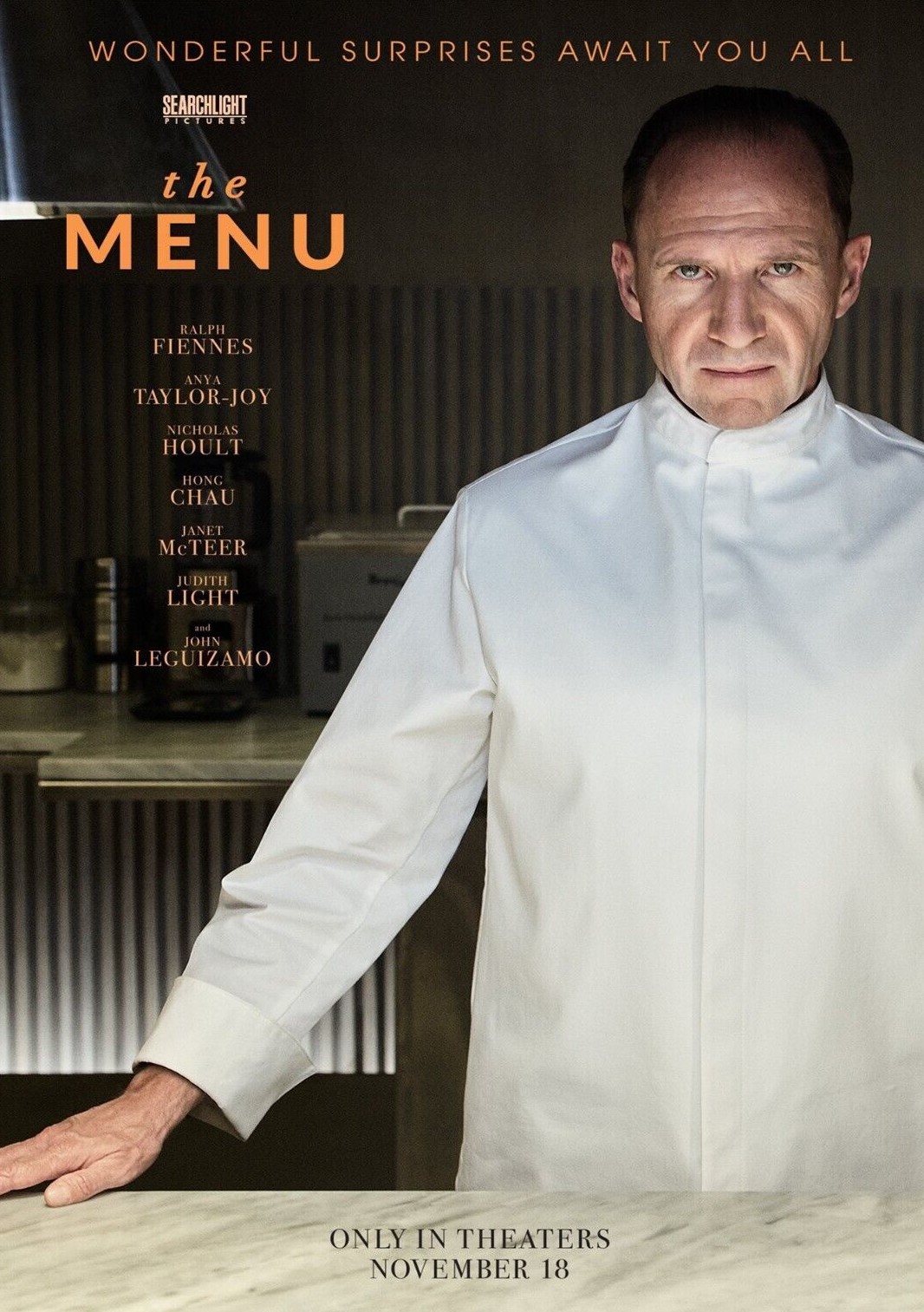

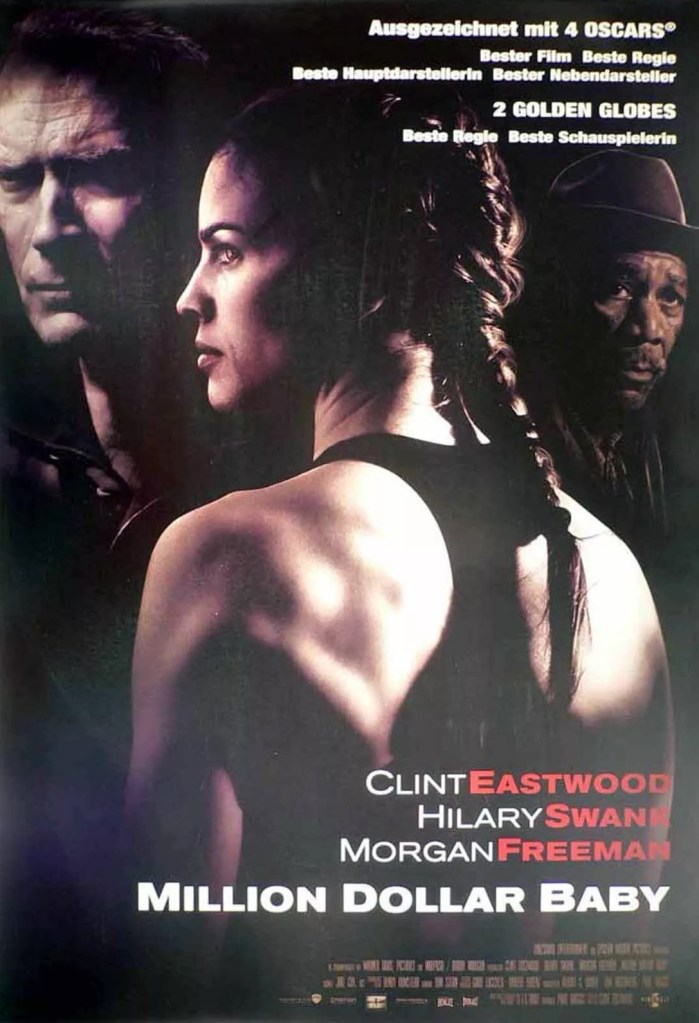

similarity between this old poster and the new one.

There’s none of that here. In fact, this all seems deliberately damped down. The tale is not told in faux documentary style and there’s no grandstanding. And yet this is one of the best directed movies I’ve ever seen. With no scene-stealing, it flies, and when it lands it’s with a thoughtful air. Just when you think it’s going to head off in he direction of one of two cliches – the high-risk pregnant wife giving birth at a dramatic juncture in the trial, or some zealous cop undertaking an equally dramatic last-minute investigation that tips the trial ass over tip – it damps down on those two.

The set up is ingenious. Recovering alcoholic Justin (Nicholas Hoult) discovers in the course of the murder trial on which he is a juror that he not only knows more about the incident in which the girlfriend of accused is killed, he may even be the accidental cause of her death. On the night in question he was nursing a drink in a bar and noticed the couple having an argument. Driving home on a wild and stormy night, he has a recollection of hitting something, knows it’s not, as he told he told partner Allison (Zooey Dutch), a deer.

Because, after several years of sobriety, he should never have been in a bar in the first place, and because there’s no evidence to the contrary – a field sobriety test should he have reported the incident – it’s automatically assumed that he would have consumed the whisky he bought in the bar. The hint of DUI would condemn him to 30 years in prison and not the new life as a father he has fought hard for.

So, in a ironic twist on Twelve Angry Men (1957), he’s the only person who stands up for the accused, but out of guilt rather than as with Henry Fonda an uplifted sense of morality. Guilt has certainly struck deep. For it’s insane for him to fight for the man’s innocence, to even raise questions of doubt, when everyone else is convinced he’s the killer. If the man is convicted, Justin will be let off. A hung jury might be a better outcome. A second trial would likely still end in conviction, as the circumstantial evidence and the accused’s drug-running background count against him, but at least Justin will not blame himself for sending an innocent man to prison.

The thing is, we don’t want Justin to be guilty. It’s an accident. Could have happened to anyone. At worst, had he fessed up at the time he would be cleared of any accusation of DUI, given the benefit of the doubt, what with the driving conditions and the fact that the victim was inebriated. He’s turned his life around. He adores his wife and looks forward to fatherhood.

He’s not the only one conflicted. Some of the jurors just want the trial over as fast as possible to get back to more pressing domestic issues. One character is dead set against anyone with anything to do with drugs. Overworked prosecutor Faith Killibrew (Toni Collette) is more concerned with a political future, running for district attorney. Ex-detective Harold (JK Simmons) commits the grievous sin – for a juror – of doing a bit of investigation on his own and is chucked off the jury.

What little information he does collect ends up with Faith. As a prosecutor she wants people put away, not let off. And she’s amassed sufficient evidence against the accused to get him sent down. So she’s not inspired with a desire for justice, the kind of firebrand character that would turn up in any other courtroom drama, digging away for an eternity, refusing to accept guilt as presented. She’s not a beacon for doing the right thing. Rather, the kind of person who doesn’t like the idea of nagging doubt upsetting her well-ordered life.

Given how many Clint Eastwood pictures end in violent showdown, perhaps his biggest directorial coup here is finishing the picture without that episode, it’s more reminiscent of the scene in American Gangster (2007) where Denzel Washington emerges from church to be confronted by a battalion of cops.

Couple of flaws – forensics so derelict there’s no suggestion that the blunt instrument that killed the victim could be a car is explained away by overworked scientists. That Faith doesn’t notice the photos of Justin sprayed around the house of Allison during her investigation reveals just how cursory a box-ticking exercise the detection is in her eyes.

Most of this plays out in the tortured eyes of Justin and in the unseen mind of Faith. With Justin, conflict is upfront, with Faith buried deep, laboriously roused from slumber.

Apart from Toni Collette and Nicholas Hoult, reunited after over two decades from their mother-and-son turn in About a Boy (2002), there is some distinctive playing – though under-playing would be more appropriate – from JK Simmons (Whiplash, 2014) and Kiefer Sutherland (The Lost Boys, 1987).

The boldness of the narrative – debut from screenwriter Jonathan Abrams – takes your breath away, avoiding the obvious route of concentrating on the innocent man, or on devious counsellors (all is played straight here) and the usual courtroom theatrics.

Absolutely superb performance from Hoult, who virtually has to do everything through his eyes. Had he been more over-the-top, Oscar would certainly have come calling, but deprived of that it’s an even more convincing performance. The low-ball direction swings this into a different class of courtroom picture, putting the audience in the situation of wanting the “bad guy” to get off.

Go see. Let Clint make you day (for likely) one last time.