I always approach cult with some unease. You never know why a film has fallen into the category. It could simply be awful and resurrected with glee because someone has cleverly constructed a sub-genre called So Bad It’s Good – check out Orgy of the Dead (1965) or Can Hieronymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humpe and Find True Happiness? (1969). Or it’s been a surprising flop first time round and discovered an audience through VHS and DVD – The Shawshank Redemption (1994) the forerunner in that field. But the plusses – well-made, great characters, some standout scenes – in the Stephen King adaptation were so obvious and the studio put a lot of dough behind re-marketing it to the at-home audience that it was not so surprising that it found a better response second time around.

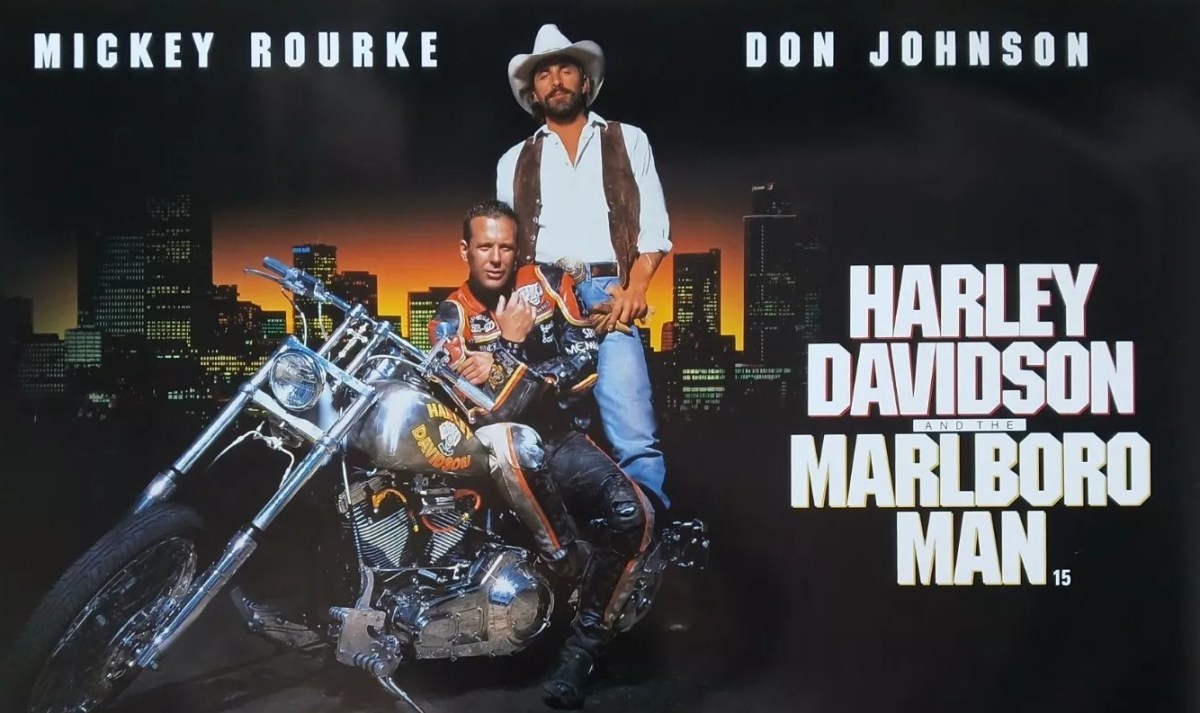

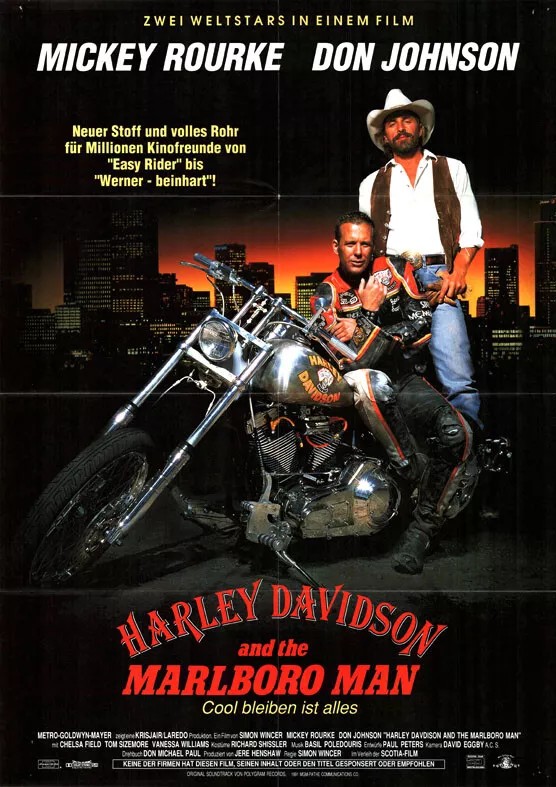

But Harley Davidson and the Marlboro Man did not, as with The Shawshank Redemption, come garlanded with seven Oscar nominations, and the stars had considerably less marquee appeal and peer acceptance than Tim Robbins (The Player, 1992) and Morgan Freeman (Driving Miss Daisy, 1990). Mickey Rourke (9½ Weeks, 1986) and Don Johnson (The Hot Spot, 1990) had not only mostly blown their status in the Hollywood hierarchy but only seemed one newspaper headline away from further notoriety.

That it works – and so well- relies on mix of several ingredients. In the first place it’s a throwback to the buddy movie, the easy camaraderie between Harley Davidson (Mickey Rourke) and the Marlboro Man (Don Johnson) has obvious precedents from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and clearly is some kind of homage to the Paul Newman-Robert Redford picture since it pinches three of the elements that made the western such a box office smash.

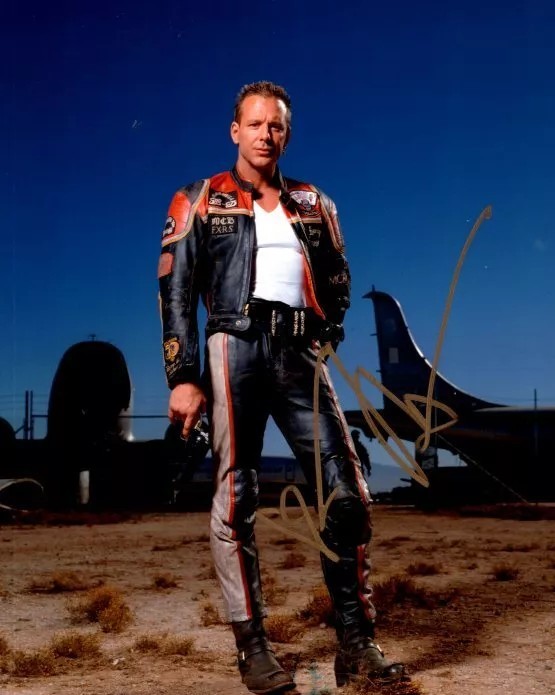

Secondly, our fellas do bad for a good – if somewhat lopsided – reason so aren’t true criminals and, in any case, earn a get-out-of-jail-free card because it turns out they’ve robbed from proper bad guys. Thirdly, there’s a terrific robbery and street shoot-out. Fourthly, it draws on the spaghetti western in the costume department, repurposing the top-to-toe dusters into black leather, an idea that would be snatched up by the likes of The Matrix and quintet of bad guys toting machine guns and dressed in black picked up not only by The Matrix but also by Men in Black (1997).

You could argue that a better director than Simon Wincer (Harlequin, 1980) would have done more visually with the leather-clad gangsters emerging from a vehicle and producing a solid wall of lead – perhaps through slo-mo or taking more time to concentrate on their sudden appearance – and made it a scene that might stand up to the ambulatory episodes in The Wild Bunch (1969) or Reservoir Dogs (1992). Even so, quite simply, it is a stunningly arresting piece of cinema.

But the real reason this works is that the two main characters are so human. Harley is given to philosophizing and wondering (in the manner, it might be said, of Butch Cassidy) and Marlboro loses out in love. While they fall into the category of endless drifters, an aversion to commitment, living easy, and more in love with their bikes than anything else, they are almost winsome in their innocence, as if everyone else will just fall into line with their world view.

That’s cult for you.

Anyways, we are duped into thinking this is going to be a John Wick-Die Hard wild ride from the opening scenes where both dudes prove mighty handy with their fists, Harley preventing a gas-station robbery, Marlboro taking on poolroom cheats in a bar. The plot only kicks in when they discover that the bank is planning to foreclose on their favorite bar. Needing to get their hands on a quick $2.5 million, the boys decide to do a bit of foreclosing themselves, taking the required sum from the bank in question, organizing a neat heist only to discover they’ve not stolen money but drugs.

Being smarter than your average hood, they swap the drugs for the dough but don’t take into account that the villains are smarter than the average thug and aren’t in the business of donating to good causes. The gangsters hunt them down. Harley and Marlboro could just disappear, especially once they dispose of the hidden tracking device, because they are A-grade students in the art of hiding away. Instead, honor is at stake so they set up an ambush in an airplane graveyard.

Since you’re asking, the Butch Cassidy the Sundance Kid grace notes are: Marlboro is the equal of The Sundance Kid is the shooting stakes and, in fact, like his predecessor, Marlboro manages the same trick of shooting off a character’s gunbelt; in the gunfighting stakes, Harley is the equivalent of Butch, never killed a man, absolutely useless with a pistol; and, the piece de resistance, when trapped they jump off an exceptionally high ledge into water.

Mickey Rourke and Don Johnson take the opportunity to shift well away from their existing screen personas and are thoroughly engaging. Simon Wincer keeps to a tidy pace. Written by Don Michael Paul (Half Past Dead, 2002) in his debut.

The action is top-notch, all the characters are well-drawn, the women not just bed fodder, usually brighter than the men. Terrific roster of supporting cast including Chelsea Field (The Last Boy Scout, 1991), Tom Sizemore (Saving Private Ryan, 1998), Robert Ginty (The Exterminator, 1980), Daniel Baldwin (Mulholland Falls, 1996), pop star Vanessa Williams (Eraser, 1996), Giancarlo Esposito (Megalopolis, 2024), Tia Carrere (Rising Sun, 1993) and Kelly Hu (X-Men 2, 2003).

The kind of movie where you wish they would do it all over again. Had the movie been a success a sequel would have been a shoo-in. As it is, we’ve only got this, so enjoy it while you can.

Catch it (for the moment) on Amazon Prime.