Let me stop you right there. This isn’t a review of this particular movie, you’re probably sick to death of those already, and it’s not some kind of Scorsese retrospective, but an expression of what it’s like to live through the transformation of one of the greatest directors Hollywood has ever produced. That zipping excitement when you first encounter a new Hollywood animal and when he charges down a different track or seems to lose control.

Catching up on a director’s life work via a carefully-curated retrospective hasn’t got an ounce of the flavor of living through it, from the days when film festival break-outs were not the carefully-orchestrated distribution and publicity machines they are now.

I first encountered Scorsese before a clever journalist had coined the rather derisory notion of a Brat Pack, when the director was just another new voice clamoring for attention in a world of considerably more cinematic noise than exists today, when MCU and streaming didn’t exist, and audiences could find massive variety every time they attended the cinema.

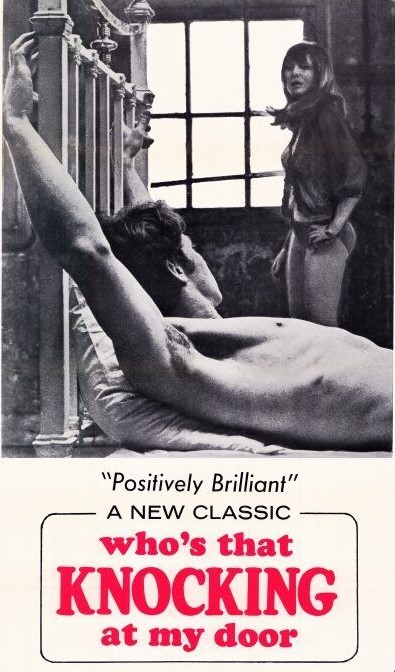

Who’s That Knocking at My Door slipped through the arthouse cracks in 1967 – the year of The Graduate, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night, The Dirty Dozen and El Dorado. I didn’t see it then. I would be surprised if anyone did. Nobody was ready for that brash style with its insistent use of pop/rock music. I caught up with a few years later when the Scorsese we know now was still in embryo form.

Sure, Mean Streets (1973) gave strong indication of the gangster path towards which Scorsese was inclined, but it wasn’t so obvious then that he would make that genre his own, not when he interspersed that with a tale of Depression-era hobos, Boxcar Bertha (1972), and Alice Doesn’t Live Here (1974), a proto-feminist narrative whose stunning tracking opening set out his technical directorial credentials. And it was anybody’s guess which way he’d go from here.

And I doubt if anyone expected Taxi Driver (1976), the moody glimpse of the New York underbelly with a psychopath hero, and certainly after that exploded at the box office and had critics purring, nobody would guess his career would take a musical turn, New York, New York and The Last Waltz in consecutive years. You might consider Raging Bull (1980), prototypical Scorsese. But the truth is, he was never typical. He jumped from project to project in a manner that only appeared to make sense to himself.

Some choices were so atypical you wondered if there had been any through-thread – what possibly connected King of Comedy (1982) to The Age of Innocence (1993) and Hugo two decades later. Certainly, when he imbibed a deep spiritual draft, you could make a thematic connection between The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Kundun (1997), and Silence (2016).

But by this point he had achieved Hollywood nirvana, the mixture of critical adulation that put him top of the hitlist of those studios with one eye on the Oscars and bouts of box office glory that kept the same studios sweet. If he ever felt the need to revive a fading career he could churn out the likes of apparently mainstream but dark-tinged Cape Fear (1991), The Aviator (2004), Shutter Island (2010) and The Wolf of Wall Street (2103). And at the back of your mind, as a fan, was the question of how long would it take him to return to the gangsters. If you had Goodfellas (1990) forever etched on your mind, Casino (1995), Gangs of New York (2002), The Departed (2006) and The Irishman (2019) seemed almost always within reach.

Of course, he can hardly be separated from Robert DeNiro, his go-to star, ten teamings in all including the current number. And for a DeNiro substitute, Scorsese didn’t go far wrong with Leonardo DiCaprio, six including the new one. Stars with an edgy side were attracted to Scorsese and vice-versa.

It’s perhaps no coincidence that DeNiro and DiCaprio play murderous relatives in Killer of the Flower Moon, but the performances both deliver are so subtle, so far removed from what Scorsese’s asked of them before, as to point them both in the direction of the Oscar.

You think you kind-of know what you’re going to get with Scorsese, but, more than any other director, he whips the ground out from under you. Killers of the Flower Moon is bereft of the Scorsese trademarks, voice-over, exuberant violence, thumping soundtrack.

So when you’ve been watching his movies for over half a century, you look on him as you might a favored son, delighted in his achievement. But you don’t want him to stop, you want him to keep going. There must be one more film in him. Like Ridley Scott, he’s more bankable than ever, especially if the streamers are looking for a short-cut to hooking up with the best talent available.

Like Oppenheimer, this one is unmissable.