Can we get over all this “national treasure” (a favorite of Britain) baloney, please? If we’re going to drag our esteemed acting knights of the realm out of their armchairs (you notice I didn’t say retirement because actors almost never officially retire, Kathy Bates and Gene Hackman to the contrary) could we please give them something more than an opportunity to overact and turn themselves into ripe old hams at the age of (in this case) eighty-five. Sir Ian McKellen (Gandalf and Magneto to you and me) deserves better.

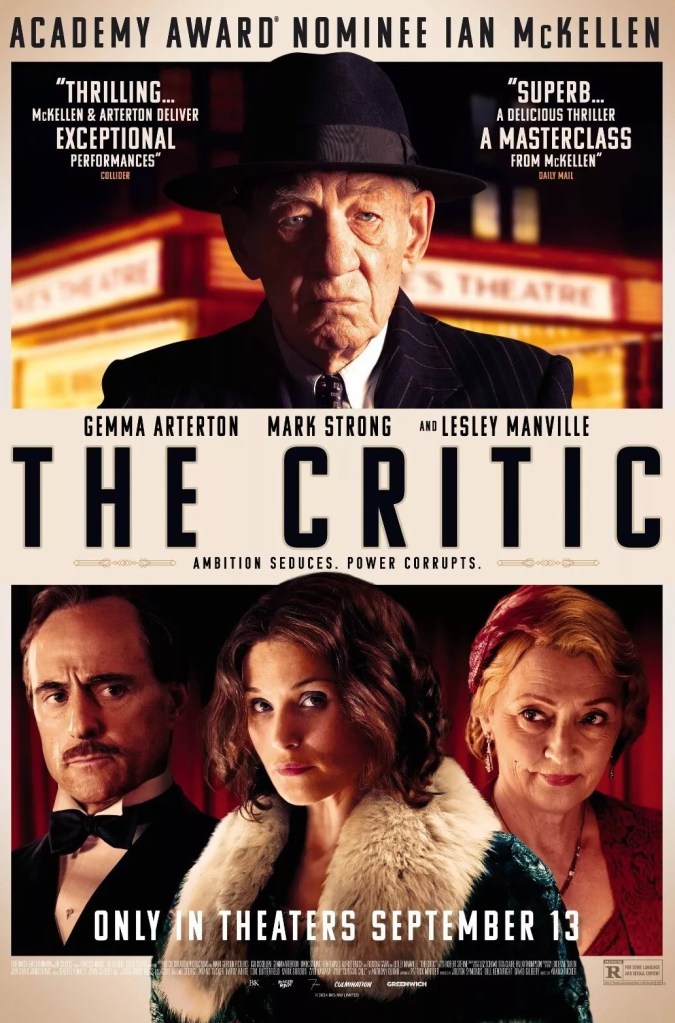

Because there’s nothing at all in this beyond Falstaffian monster Jimmy (Ian McKellen), the eponymous theater critic, relishing his power and taking revenge when’s on the verge of losing it. Frankly, if this was called The Tie-Pin Killer, the serial murderer in the book on which this is based, and Jimmy, as in that book, was relegated to a bit part, albeit a juicy one, it might have been a lot more interesting.

While it touches upon 1930s London Fascists and the plight of the homosexual (a criminal offence to participate) these are kind of tossed into the scenario as if to placate an audience who might complain this is very thin gruel indeed. Presumably, we are somehow meant sympathize with this cruel, odious, character because from time to time he finds himself confronted by blackshirts, who take a dislike to his black companion Tom (Alfred Enoch), who acts as his secretary and presumably not anything else because Jimmy prefers “rough trade.”

In revenge for being fired, he sets up actress Nina (Gemma Atterton) to seduce his employer David Brooke (Mark Strong). Blackmail’s the tool of reinstatement. Apart from general actor insecurity, it’s not entirely clear why Nina should be so determined to keep in Jimmy’s good books. There’s some unbelievable stuff about becoming attracted to acting through reading his articles, which seems quite bizarre since his nasty reviews would put people off going, as he proudly explains is one his aims.

So Nina prostitutes herself for a good review. Yep, must happen all the time. And despite her supposed success – these are, after all, West End plays she is starring in – she lives in a bedsit where hot water is rationed. But she is, romantically, in a bind. She’s just dumped her married lover Stephen (Ben Barnes) whose wife Cora (Romola Garai) just happens to be the daughter of Brooke.

And although Brooke’s wife is “bonkers” (though that’s very much on the periphery) he’s that old-fashioned upper class English gent who only feels shame at adultery when he’s caught out and then of course does the right thing which is to blow his brains out. Which leaves Nina racked with guilt which drives her, as it would, back into the arms of Stephen only for him (another adulterer with principles) to reject her on the grounds that she slept with his father-in-law. When Nina begins to talk about confessing to her role in conspiracy, what’s an upstanding chap to do but drown her in the bathtub?

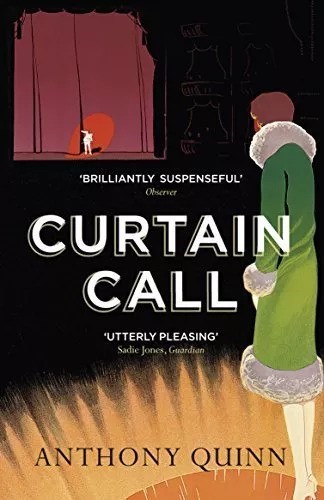

Crikey, and we complain about the plotting in the multiverse. This is just bonkersverse. Presumably, Oscar-nominated screenwriter Patrick Marber (Notes on a Scandal, 2007) happened upon Anthony J. Quinn thriller Curtain Call in which Jimmy exists on the periphery of the actual narrative though as a larger-than-life character and decided to forget the whole tie-pin killer thing and rearrange the tale so it revolved around McKellen in the hope nobody would notice, in the midst of McKellen roistering and boistering to his heart’s content, the lack of any sensible tale.

You could certainly have more easily hooked it on Nina, who falls into the Patrick Hamilton category of easily-led character on the edge with impulse inclined to cut her adrift.

If you want ham, McKellen’s your man, none of the subtlety which has impelled other performances. Gemma Atterton (The King’s Man, 2021) has a few moments tormented by conscience but the part is woefully underwritten. This is the reined-in Mark Strong (Tar, 2022) rather the one with the veins standing out on his neck. Lesley Manville (Mrs Harris Goes to Paris, 2022), potentially another future national treasure, has a brief role as does Romola Garai (Atonement, 2007).

Maybe wanting to burnish his artistic credentials, director Anand Tucker (Leap Year, 2010) is predisposed to the extreme close-up and for viewing a scene in extreme long shot through a corridor, window or door.

Jimmy would give have slated this.