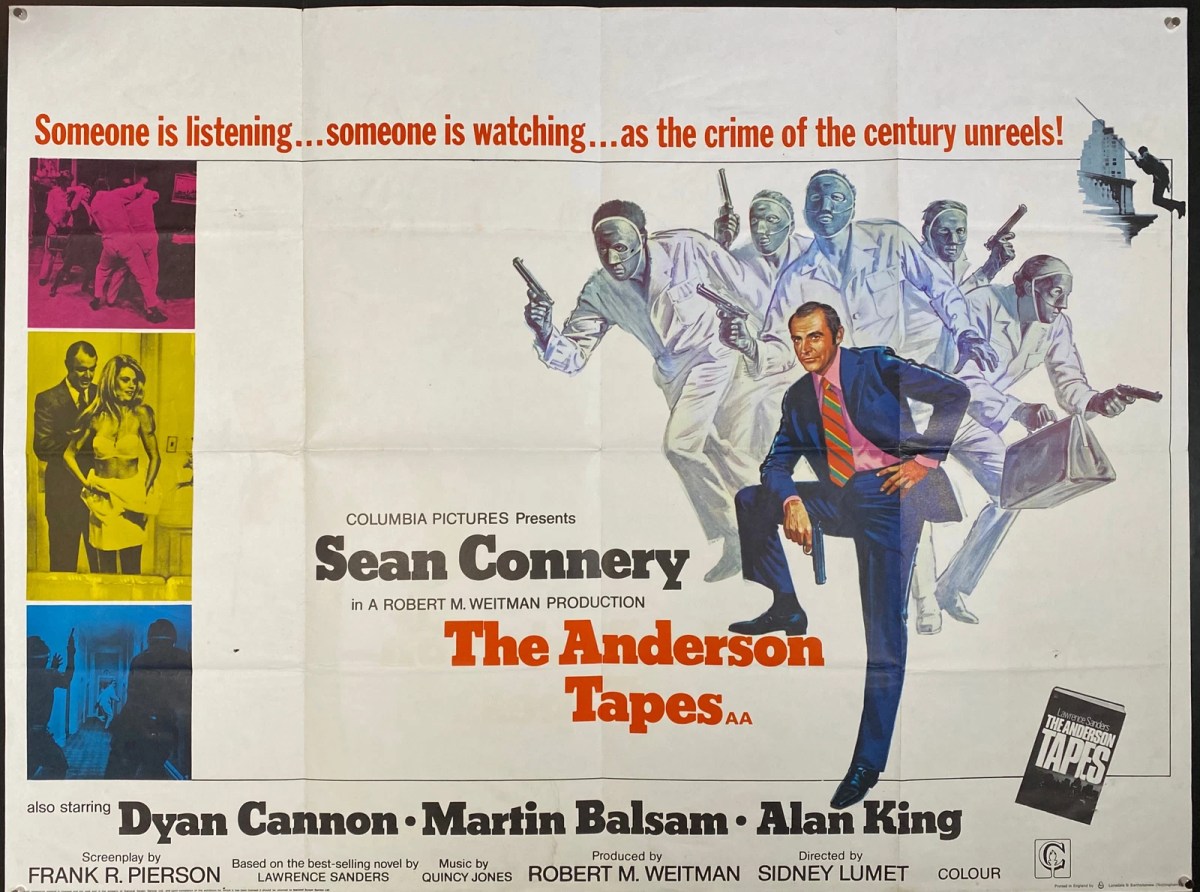

Had Sean Connery played the character of Duke Anderson as written, rather than reigniting his career it would have risked killing it off. It was already a significant ask for a star to shift from portraying good guys – even if James Bond had an immoral streak – to essaying a bad guy, though here was precedent – Paul Newman in Cool Hand Luke (1967) and Steve McQueen in some style in The Thomas Crown Affair (1968).

However, it would be difficult enough for audiences to accept a star who is two-timing his girlfriend, never mind one who in turn exhibits sadistic and masochistic streaks.

So that was the first problem for Oscar nominated screenwriter Frank Pierson (Cool Hand Luke) and not surprisingly he settles on the elimination route. The character’s sexual tendences are never mentioned. Theoretically, Pierson gets round the two-timing issue by merging the two girlfriends, Ingrid Macht and Agnes Everleigh, into one, Ingrid Everly (Dyan Cannon).

But Ingrid Everly has little connection to Agnes beyond that she lives in a luxury apartment. In the book, Agnes is a casual pickup, a woman he meets in a bar. She was separated from her husband and retained possession of the apartment, which was in his name. In order to find the legal grounds on which he could regain the apartment, her husband had bugged the apartment.

In the film, the apartment is still bugged, but by her rich jealous boyfriend Werner (Richard B Shull) so, technically, it’s Ingrid who’s doing the two-timing. Whereas in the book Agnes’s husband is perfectly happy for her to be entertaining other men as he hopes this will enhance his chances in the divorce settlement, in the film Werner is the opposite, and does not embrace the notion of what he views as his “property” being involved with anyone else. Ingrid, who was genuinely Anderson’s ex-girlfriend, in the film comes to realize a sugar daddy is a better bet than a criminal no matter how handsome. The only oddity in the picture that when Anderson is confronted and Werner explains that, via his surveillance, he knows Anderson is planning a robbery, that he doesn’t give two hoots about that.

Other changes are equally sensible. In the book, the robbery is intended to take place in the middle of the night. The ploy the thieves planned to use to get the apartment residents to open their doors was that the building was on fire. This wasn’t by triggering the fire alarm but by running from door to door, shouting “Fire! Fire!”. Pierson gets rid of that cumbersome device.

He also knocks into touch the notion that Tommy (Martin Balsam) would find supposedly legitimate reason to gain access to apartments to scout the premises in advance by pretending to be doing a survey for a civic group. In the book Tommy is a two-bit low-level hood and not involved in the actual robbery but with some knowledge of art and expensive items. In the film he transforms into a smooth-talking antiques dealer and Frank Pierson comes up with the idea that the management of the building is planning a refurbishment and wants to ensure that residents have the opportunity to align their interior décor with what is being planned.

In the book as well as eight luxury apartments, there are, on the ground floor two businesses, a doctor and a psychiatrist, but these are also thrown on the scrap heap, although in the book the doctor turns out to have $10,000 hidden away from the taxman as well as medicines that could be sold on the black market.

The pompous Capt. Delaney (Ralph Meeker) who organizes the offensive on the robbers, is drawn virtually word for word from the book. But there’s not room to incorporate all the criminal slang. I was especially intrigued to discover that what I always believed was called “a big job” was known to the criminal fraternity as “a campaign.” Nor the details of organizing such a robbery.

And there are a couple of interesting snippets in the book that Pierson had no room for in the movie. Firstly, author Lawrence Sanders includes verbatim a newspaper report dated 2nd July, 1968, to the effect that a new electronic communications office has been opened by the police to help cut down, initially, response times. The report included another fascinating fact. Prior to this date to report a crime the American public had to call a seven-digit number. That was reduced to the ”911” emergency number that operates today.

The second element is the call to unite all the different operations running criminal surveillance. Here, including Werner, there were four separate surveillance teams, none in contact with any of the others.

The book is a terrific read. I devoured it in one sitting. It is Sanders who introduces the flash forwards, interviews or somesuch with victims, while in real time the robbery is under way.

But the screenplay is an ideal example of how to trim a book to the bone without removing any of the essentials.

Sanders was also the author of The First Deadly Sin which was filmed with Frank Sinatra in 1980 and reviewed here earlier.