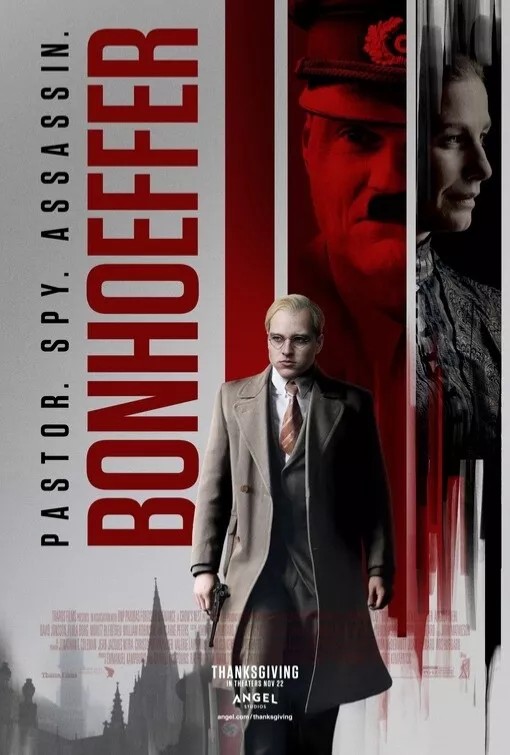

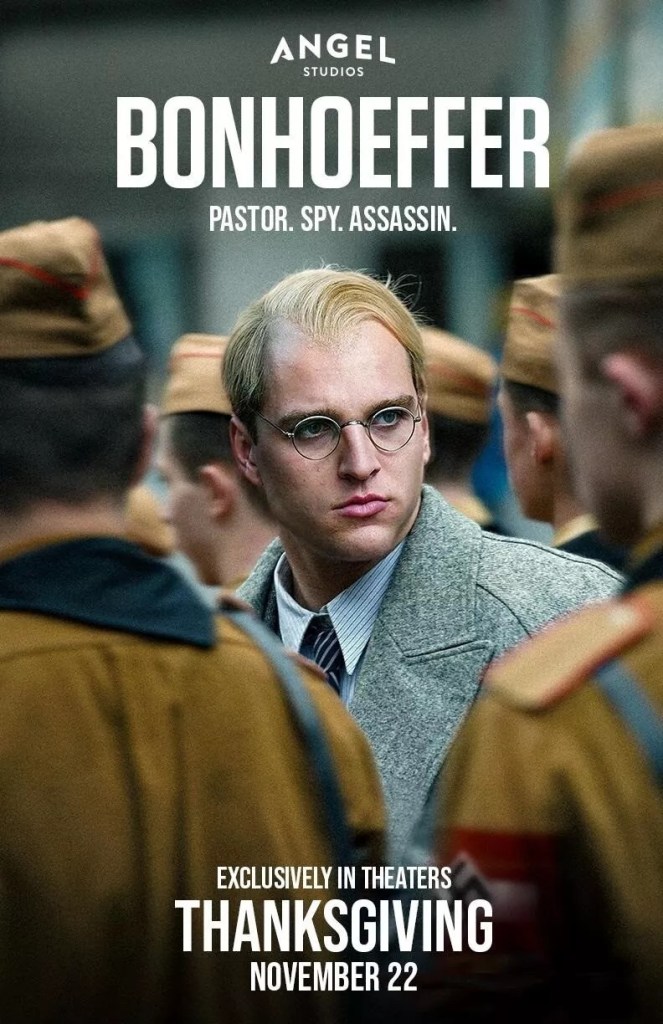

I had forgotten all I knew about Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German theologian who was hanged three weeks before the end of the war for his part in the failed assassination of Hitler. I hadn’t realized, either, that there was a virtual spate of biopics, three in the last two years and two more since the turn of the century. The name of writer-director Todd Komarnicki didn’t mean much to me either, except, to counter that obstacle, he pops up before the movie begins to remind us of his credentials, director of World War Two picture Resistance (2003), producer of Elf (2003) and writer of Sully (2017), the latter involving, he is at pains to point out, Hollywood royalty in the shape of director Clint Eastwood and star Tom Hanks.

While this is workmanlike rather than, until virtually the very last scene, inspiring, and, until the final credits, pivots on virtually a handful of his writings – from the millions of words he wrote, many that have become the kind of pithy sayings that people are apt to quote.

There’s a sense that this is for the converted and that there’s little need to remind an audience of what it should already know. While the narrative doesn’t meander, it does oscillate through various timeframes and for those unacquainted with the life it could have done with more attention to detail.

Except for one detail that resonates at the end, the childhood sequences could have been eliminated, though they reveal that his elder brother died in the First World War. Then we are pretty much pitched straight into Harlem where a colleague, Frank (David Jonsson), attending the same New York theological college, introduces him to Baptists who expound gospel music, sassy preacher Rev Powell Sr (Clarke Peters) and the devil’s music, jazz. Bonhoeffer (Jonas Dassler) gets sharp reminder of the pervasive racism when he tries to book a hotel room for his African American buddy and gets whacked in the face with a shotgun for his troubles. This makes him realize piety isn’t enough and that action is required to stand up for your principles.

He becomes one of the first to report on Hitler’s victimization of the Jews and a leader in the dissident movement at a time when the German church is supportive of the Fuhrer. He was a published author from 1930 and became a significant public figure. He promoted the ecumenical movement and spent two years as a pastor in London. He was jailed for his opposition to the Third Reich.

As I said, this is mostly a straightforward affair, and you might struggle to keep up with church politics and it’s a guarantee you won’t have any idea who the other clerics are, and none of them come alive enough for us to care about them.

The best scene, and key to his beliefs, comes at the end. The night before he is due to be hanged, a prison guard offers to help him escape. But Bonhoeffer, fearing repercussions for both of their families, turns him down. He holds an imitation of the Last Supper for the other inmates, including, much to the initial fury of the assembled prisoners, the guard. He dies not just with considerable dignity but welcoming death.

Jonas Dassler (Berlin Nobody, 2024) is stolid more than anything and it’s very much a one-note performance. Frankly, none of the acting will take your breath away. However, placed against the current political climate, this resonates more than the film possibly deserves. It’s a worthy biopic and a timely reminder that “not to act is to act.”

However, if the name Bonhoeffer has ever entered your consciousness and you want to know more this is as good an introduction as any (though in fairness I haven’t seen the other biopics and I suspect the one starring Klaus Maria Brandauer will carry more emotional heft).

This was surprisingly busy when I saw it at my local multiplex on Monday, so the name has not been forgotten.