The story of Breathless is usually told from the triumphant perspective of director Jean-Luc Godard, expressed in messianic terms as the young Frenchman who saved the turgid movie industry and inspired a new generation of filmmakers. For star Jean Seberg it provided partial redemption and a sharp plunge into a harsh reality.

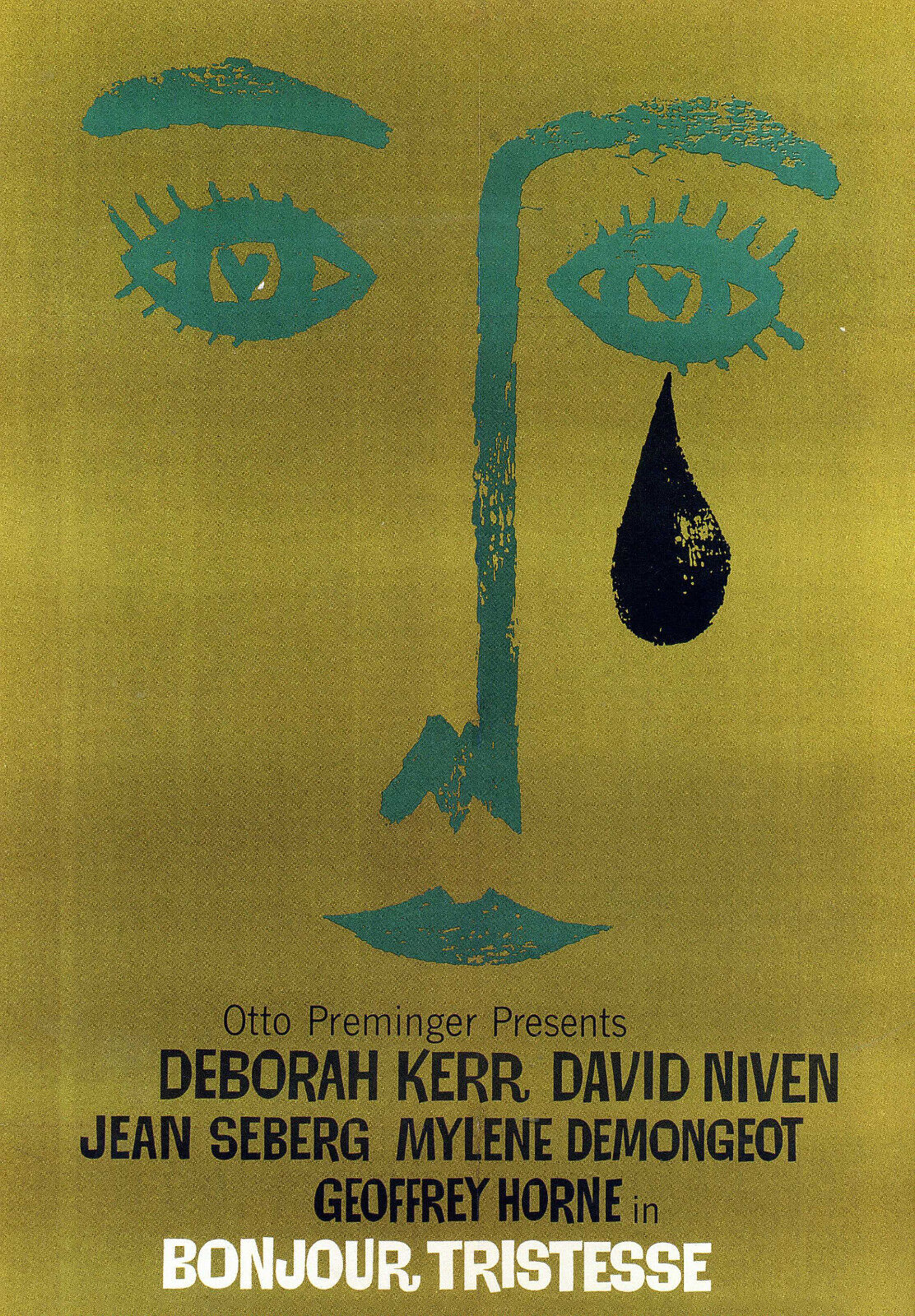

Where she had been at the mercy of Otto Preminger in her previous two films, Saint Joan (1957) and Bonjour Tristesse (1958), and for all that she loathed aspects of that experience, she was still in the Hollywood system, where a whole phalanx of people attended to your needs. Preminger had had enough of the woman he believed he could turn into a star. Both movies had flopped, her acting talent questioned.

It’s generally understood that Preminger dumped her and sold her contract to Columbia. But the antipathy went both ways. Her husband, lawyer Francois Moreuil, approached Preminger to negotiate a release from her contract. She might have wished just to be set free for nothing but given Preminger’s investment, not just salary when she wasn’t working but all the build-up that went into turning an unknown talent into a star, that was never on the cards. So, he passed her on to Columbia, to whom he was contracted, and which would take her on as a favor.

But Columbia had little idea what to do with her either. As far as that studio was concerned she was far from the finished article, a long way away from stardom. The best she could hope for was a supporting role in a prestigious production, rebuilding her career under a more sympathetic director. That appeared the most likely outcome when her name was linked to a supporting part in Carol Reed’s Our Man in Havana (1959) starring Oscar-winning Alec Guinness and Maureen O’Hara. But she wasn’t even auditioned.

When Columbia finally found something for her to do it was in the low-budget British-made The Mouse That Roared (1959), leading lady to Peter Sellers, his first as star. After that though, as far as Columbia was concerned, it would be a tumble down the credits in the American Let No Man Write My Epitaph (1960) starring Burl Ives. The British film set had none of the highwire tension of a Preminger film. She was taken acting lessons which restored some of her confidence after the mauling she had taken from Preminger.

As luck would have it, while awaiting a summons from Columbia, she was ensconced in Paris in a romantic idyll with Moreuil, who had vague notions of turning to film direction and had therefore made the acquaintance of the Cahiers du Cinema gang of critics who harbored the same dream. That brought him into contact with Godard, who was, much to her surprise since her performances had generally been lambasted, a big fan.

She was impressed by his short Charlotte et son Jules starring former boxer Jean-Paul Belmondo. Her role in his debut feature, said Godard, was based on the character she had essayed in Bonjour Tristesse. “I could have taken the last shot of Preminger’s film and dissolved to a title ‘Three Years Later’,” he explained. Still, even though there was nothing on the horizon from Columbia, she hesitated.

Godard was an unknown quantity, there was no script, and making a movie outside the Hollywood comfort zone would be a trial, a miniscule budget – $90,000 – scarcely a fortieth of that of a Preminger picture – would ensure no retinue of assistants. She would be largely on her own. Tippi Hedren had felt the same cold shock when she maneuvred herself out of her Hitchcock contract and discovered that rather than being waited on hand-and-foot by the industry’s best costume designers she had to wear her own clothes for her first job, in television.

Financially, Godard was in bad shape. Without a name – Belmondo scarcely counted – the film would be abandoned. In the absence of anything else, she signed up. But first she needed Columbia’s approval. The studio was offered $12,000 for her services and half the worldwide rights but when they stalled her husband pulled a fast one, announcing that since he was rich (untrue) Seberg need never work again and threatening that she would simply retire. Columbia took the money and ignored the rights, which cost them several million dollars.

Seberg was paid $15,000 – around $5,000 a week (the shoot lasted 23 days) – a hefty sum for an ingenue if you took that as a potentially weekly rate ($250,000 a year), but even if that was all she earned it was still six times more than the average U.S. employee was paid in a year. That was still an improvement on the $250 ($13,000 per annum) paid by Preminger in 1957.

But there was a dramatic switch in power politics. With Preminger, she kowtowed, doing what she was told, failing to stand up to the director. On Breathless, she had no trouble expressing her views and wielding her power. She walked off the set on the first day of shooting after a disagreement with Godard. That was resolved by the director chasing after her. A couple of days later she was ready to quit.

And she argued vehemently against his interpretation of her character’s actions in the final scene. Godard wanted Patricia (Seberg) to steal the wallet of Michel (Belmondo) as he lay dying. She refused to do it on the grounds that it was not in character, but later explained that it was more personal, she did not want to play a thief on screen. She had reservations about taking off her clothes for the sex scene, resolved by the couple being hidden under the bedsheets and Seberg remaining full clothed. And if she fancied a day off – a considerable indulgence on a film on so tight a deadline – she took one. Godard saved face by allowing everyone a day off.

Cameraman Raoul Coutard observed, “She didn‘t let herself be pushed around but she did cooperate.” And without the normal armada of backroom staff attending to make-up and ensuring she looked her best in every scene, Coutard fell back on the fact that she was imply photogenic and did not require the full Hollywood treatment to look her best.

Perhaps the guerrilla style of movie making appealed. Instead of rehearsals with a script set in stone and lines learned weeks in advance, Godard made up the film as he went along, turning up in the morning with a students’ notebook filled with ideas and dialogue. At times there was no written script, Godard speaking lines and the actors repeating them.

Although at one stage after a spat he threatened to deny her a close-up, in reality budget restrictions – a close-up would require filming a scene several times over – put paid to most of those. The scene in the car where the camera focuses on her an example of taking clever advantage of circumstance as the sequence, in its daring, appealed to the avant-garde.

But Godard did take the trouble to ensure that Patricia was true to her origins. As an American, her character should not speak fluent French, but make mistakes here and there, especially with gender. “It became much more colloquial and much more foreign in a way,” she said.

And much as she hated the way Preminger had imposed his ideas so strictly upon her, when left to her own devices, thanks to Godard’s improvisational style, she was at a loss. “She was very disabled because there wasn’t a script,” explained Francois. When she asked Godard for directions he would tell her to do what she wanted. Eventually, assuming the film was a mistake and would flop, she decided to “sit back and have fun.”

Although under time pressure, that was a less frightening experience than having a hundred pairs of eyes fixed on her as she spoke lines according to the Preminger dictat. But she had to come to terms with just how far down the production ladder she had fallen, a café toilet doubling as a make-up room, her wardrobe purchased from a discount store.

Godard’s inventiveness knew little bounds. For the final tracking shot, the director was pushed along in a rented wheelchair. The shot of the Champs-Elysess came from employing a postal cart. Filming began on August 29, 1959 and most of the film was shot consecutively.

Innovations included extensive use of the jump cut, hand-held camera and low lighting. Although deemed an arthouse movie by the rest of the world, Breathless opened at a commercial chain of cinemas in Paris where it was an instant hit, selling a quarter of a million tickets in its first four weeks.

While Godard and Belmondo basked in a critical and commercial triumph, for Seberg it was only part-redemption. Except at the end of the decade she was never the leading lady in big Hollywood productions, but she became an acknowledged star of French cinema, a couple of years later the third-highest paid actress in France, earning $1,750 a week ($91,000 a year).

SOURCE: Garry McGee, Jean Seberg: Breathless, Her True Story (2018), pp60-68.