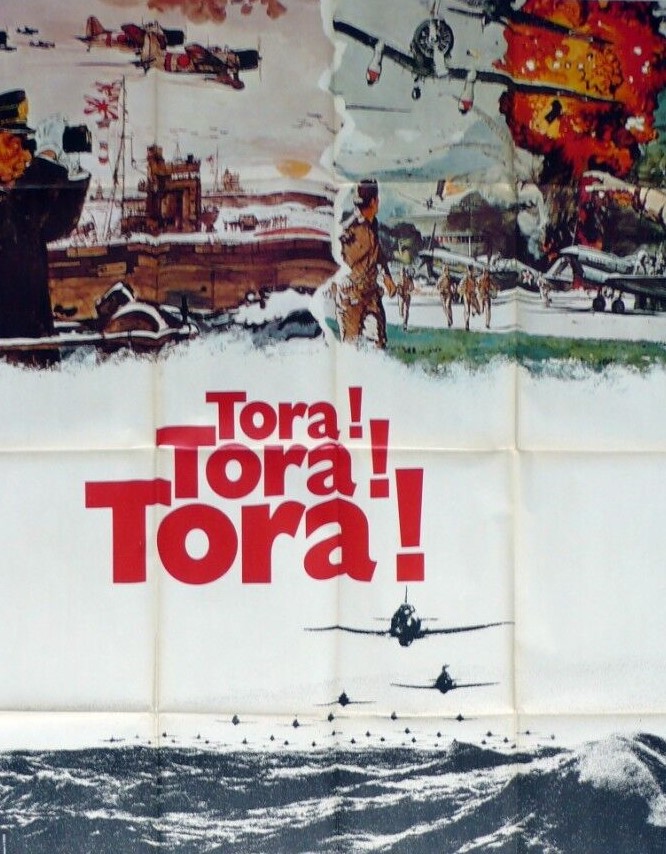

Thankfully devoid of the empty triumphalism that marred In Harm’s Way (1965) and Pearl Harbor (2001) and the gritty backs against the wall heroism and snatching some kind of victory from the jaws of defeat of The Alamo (1960) and Zulu (1964), and with a documentary-style approach much more acceptable these days than then, there is an immense amount to appreciate and absorb in this last-gasp 70mm roadshow from a financially flailing Twentieth Century Fox.

Shorn, too, of the traditional all-star cast bar Jason Robards (Hour of the Gun, 1967) – who might not count – nor the regiment of rising talent stuffed into such epics in the hope one might catch the eye and float to the top. And there’s no room to ram in a distracting romance such as in the previous and future films focusing on the military disaster. Instead, stuffed with dependable supporting players like Martin Balsam (Harlow, 1965), E.G. Marshall (The Chase, 1966) and James Whitmore (The Split, 1968) stops audience rubber-necking in its tracks, unlike producer Darryl F. Zanuck’s previous The Longest Day (1962), in favor of forensic analysis of what went wrong in the defence and what went so brilliant right in the attack.

Like most of the best war epics – The Longest Day, Battle of the Bulge (1965), taking an even-handed approach in presenting both sides of the battle, except here you could argue considerably more time is spent with the Japanese, beginning with the opening credits where the camera floats in and around a giant battleship. Despite the sudden attack which went against all the traditions of war – a timing error apparently – the Japanese are presented as honorable and even arguing against going to war as well as worrying about the consequences of poking the tiger.

And there is none of the endless owing and scraping and not attempting to rise above your station in the traditional Western-view of the Japanese. Here, from the outset, superior officers are questioned possibly in manner that would be permitted among the opposing forces.

The first half is given up to the superb organisation of the attack, including the bold use of using aerial torpedoes – proven to work by the British in an earlier assault on a harbor without the apparent depth of water required – and contrasting it with the general U.S. ineptness, bureaucracy, interdepartmental battles and overall lack of preparation even though several personnel believed an attack imminent. The Yanks had even broken the Japanese codes so could easily have taken heed of obvious omens, had working radar on site though its employment was handicapped by being limited to three hours a day and initially lacking a means of communicating findings. Someone had even worked out that the Japanese would need six aircraft carriers to mount an attack and that the ideal time would be early morning on a weekend, someone even predicting an attack down to the exact time except a week out.

Of course, the U.S. at this point was not at war and so could be excused switching off in the evening or being uncontactable in the morning because they were still out carousing from the night before or sedately riding a horse. While there is a growing sense of alarm, the chain of command is woefully stretched often in the wrong direction and at one point stops before it reaches the President.

Fearful of sabotage, the Americans shift planes away from the perimeter of airfields smack bang into the runway where they can be more easily destroyed. Perhaps the greatest irony is that in shifting the U.S. fleet from its home base in San Diego, the Americans made such an attack possible.

When it gets under way, the battle scenes are superb, especially given none of the CGI Pearl Harbor could call upon, and yet with the U.S. aircraft carriers by luck still at sea failed to deliver a killer blow for the Japanese.

It’s handled superbly by director Richard Fleischer (The Boston Strangler, 1968), Kinju Fukasaku (Battle Royale, 2000) and Toshio Masuda (The Zero Fighter, 1962). The American flaws are dramatized rather than being dealt with by info-dump. Larry Forester (Fathom, 1967) and long-time Akira Kurosawa confederates Hideo Oguni (Ikiru, 1952) and Ryuzo Kikushima (Yojimbo, 1961) fashioned a sharp screenplay from mountains of material.

Long rumored to be a box office flop it turned out to have made a decent profit, albeit not in the U.S.

The documentary approach adds immensely to the movie and it remains one of the all-time greats precisely because of the lack of artificial drama.