The blue collar worker has not taken up much of Hollywood’s time. There was a movie disdainfully called Blue Collar (1978) but the best pictures about people doing actual physical hard work was Five Easy Pieces (1971) about a fella who was putting in the long yards to spite his old man and The Molly Maguires (1968) which was more about politics and anarchy. The British did it better, but concentrating on the monotony, in such ventures as Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) and Gold (1974). though images of anyone getting their hands dirty was fleeting

Generally, films about work are movies or television series about management (Wall St, 1989 or Succession, ) and/or a soap opera (Dallas). Most commonly, there’s a picture about farming – Grapes of Wrath (1940), The River (1984)– but there’s very little farming involved. You get a better idea of what it’s like to till the earth from the recurrent image in Gladiator (2000) when Maximus smells the soil.

Until Taylor Sheridan came along and realized the immense dramatic potential of actual hands-on dirty work and rode Yellowstone (2018-2024) to enormous critical success and sufficient commercial endowment to be able to write his own ticket. I rarely buy DVDs these days, not because I’ve already got thousands of themd, but because that old impetus is long gone, the days when we desperately waited for a movie to turn up at the video rental store, one that you couldn’t otherwise get your hands on or missed on its cinema release, one that you wanted to own so you could watch it again and again.

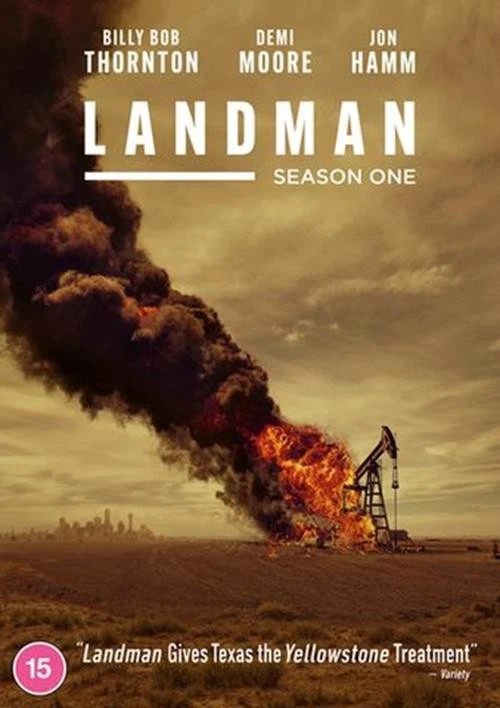

Now I tend to buy DVDs if I don’t have a subscription to a particular streamer. I did it for Yellowstone and I did it for this Taylor Sheridan enterprise Landman.

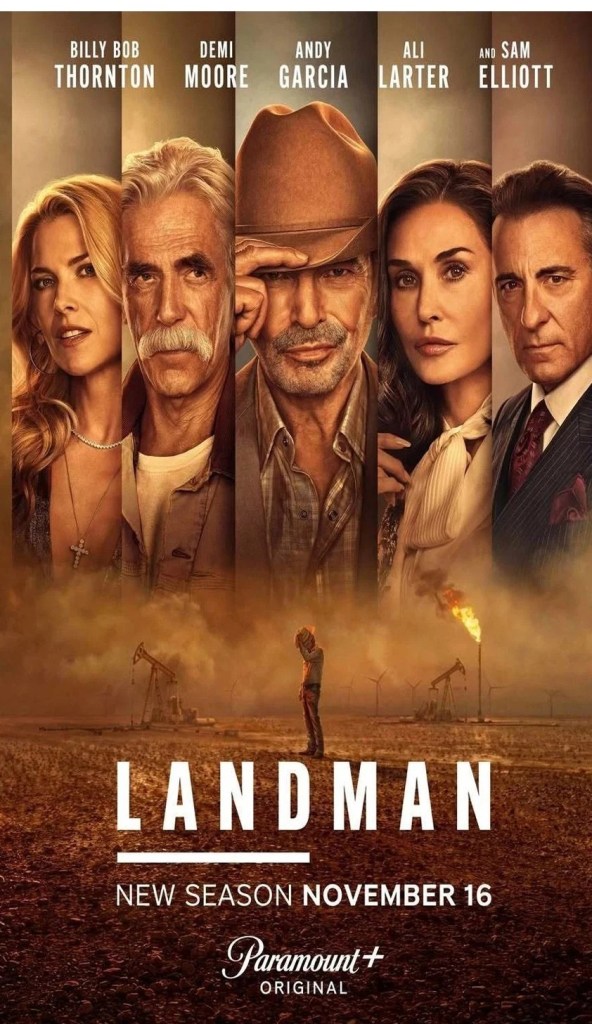

On the face of it, this might seem like another oil or big business venture where the emphasis is on wheeling and dealing and heirs fighting over money and how to spend it and everyone just the hell arguing because that’s instant drama. The element devoted here to wheeling and dealing is negligible, restricted to oil tycoon Monty Miller (Jon Hamm), one whisky away from a heart attack, at the other end of a phone getting agitated and taking out his frustration on anyone in sight.

Instead, it’s about very dirty work, the kind where workmen come home saturated in filth and the kind where you could in a flash lose your hand or your life. There have been four instantaneous deaths so far and I’m only at episode six of Series One. We’re not in the all-action Hellfighters (1968) business of quelling fires, but in the dull maintenance part of ensuring that wells with 35 years accumulated wear and rust are kept going.

Don’t think I could wait for the DVD.

It’s the job of Tommy Norris (Billy Bob Thornton) to make sure these wells keep producing and all it takes is a stray spark or a moment’s lack of concentration and the coffins are mounting up. Along the way, we are brought up to speed on how the oil business works – or doesn’t.

Exposition used to be a hell of an issue for screenwriters until those Game of Thrones dudes invented “sexposition” where acres of naked flesh kept the audience awake through the dull stuff. Here, however, Sheridan manages something of a coup by having Monty or Tommy gush like oil wells while setting others right about the business.

This series kicks off with an oil tanker tearing along at 60mph crashing into small airplane that’s parked on a road to disburse its cargo of drugs. And that triggers two increasingly fraught, sometimes thrilling, elements. First, we’ve got the drug dealers seeking revenge and recompense. Secondly, you’ve got legal repercussions in the shape of the all-time Jaws of a lawyer Rebecca Falcone (Kayla Wallace) and how Tommy has to snake through the vagaries of the law, not, for example, pursuing thieves who steal the company’s planes or tankers to shift their ill-gotten gains because the law will invariably impound such items of transport for the couple of years it takes to get a case to court and because the drug dealers are only borrowing them for a short period and return them after use.

On top of that, Tommy is trying to blood son Cooper (Jacob Lofland) into the business, starting off as a roughneck, while turning up out of the blue are glamorous ex-wife Angela (Ali Larter) and daughter Ainsley (Michelle Randolph), who views philanthropy as a tax dodge.

There’s some terrific humor from Tommy’s housemates Dale (James Jordan) and, mostly in reaction shots, Nathan (Colm Feore).

You won’t have seen any of these storylines before, not even the returning wife and daughter, because all the characters are so original and the performances so powerful. Billy Bob Thornton (Bad Santa 2, 2016) has eschewed all his acting tropes, dumped the sarcasm and temper tantrums, and instead plays a weary debt-laden foreman who fails to resist the lure of his trophy wife.

I remember Ali Larter from such unchallenging fare as the original Final Destination (2000) so she is something of a revelation. While Angela is as vapid as any other trophy wife, majoring on shopping and looking good, actually she’s an education in how an ageing trophy wife stays the course. She is a fabulous cook, for starters, and she puts in the hours at the gym to keep trim. But she’s also a manic depressive and so her emotions spin on the toss of a coin, extremely charming, not to mention endearing, one minute, a venomous snake the next. This is a performance reverberating with depth that should qualify for an Emmy.

Jacob Lofland (Joker, Folie a Deux, 2024) is Gary Cooper reborn. The stillness, the reticence, and yet when necessary, taking no prisoners. He’s way out of his depth not just with the crew he’s landed with, but in unexpected romance with young widow Ariana (Paulina Chavez). But that’s not the last of the star-making turns. Kayla Wallace (When Calls the Heart series, 2019-2025) is phenomenal as the ball-busting lawyer eating up misogyny for breakfast and heading for a showdown with anyone in sight. Sassy Michelle Randolph (1923 series, 2022-2025) has many of the show’s best lines.

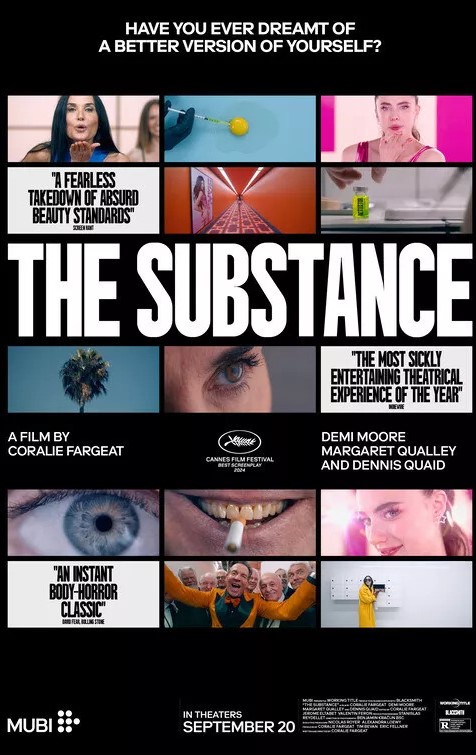

And that’s before we come to Jon Hamm (Mad Men series, 2007-2015) and Demi Moore in a more believable role than The Substance (2024). And the simple earworm of a score by Andrew Lockington (Atlas, 2024).

Truly original and riveting.