It should have been Frank Sinatra in the leading role, not Newman. Sinatra acquired the rights to the Walter Tevis semi-biographical novel published in 1959. When Sinatra moved onto something else and director Robert Rossen took up the slack still Newman should have been ruled out courtesy of a planned re-teaming with Elizabeth Taylor – they had worked together on Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1959) – for the screen adaptation of Broadway hit Two for a Seesaw. Bobby Darin (Pressure Point, 1962) was being lined up instead. When illness put paid to Taylor’s involvement, Newman would have remained tied to Two for the Seesaw except he had co-star approval and none of the actresses suggested measured up.

Based on reading half the script, Newman, calling his agent at six o’clock in the morning to confirm interest, jumped at the role. Though Exodus (1960) had been a success, and he had managed to ease himself out of his contract with Warner Bros, he was not considered hot box office and he needed a part not just to consolidate his commercial standing but to provide a professional springboard that would shape his career. His previous outing, Paris Blues (1961), hadn’t carved out a clear path. As well as his salary, the actor was in line for ten per cent of the profits.

Initially, the picture was backed by United Artists and it featured in their adverts in the trade magazines in 1959. The studio had shelled out an advance to Rossen to option the rights. But when the director couldn’t find a “box office star as insurance” UA pulled out. By this point, the end of 1959, there was at least a screenplay, Rossen having called upon the services of Sydney Carroll (Big Deal at Dodge City, 1966).

Rossen shopped the package to Twentieth Century Fox which, somewhat surprisingly, signed up to the project when no major star was attached, especially as, according to Rossen, the picture “pulled no punches” with its “frank approach to people and life.” UA had promoted itself as the go-to studio for independents but by Rossen’s reckoning Fox was superior in that department because backing the movie “took some guts.”

Fox chief Spyros Skouras wasn’t keen on the title, believing, understandably, that The Hustler might signal to audiences that it was a story about prostitution. It was changed first of all to A Stroke of Luck and then to Sin of Angels. However, UA objected to the latter title on the grounds it had already registered a similar title The Side of the Angels and with some reluctance Skouras agreed to go with the original title.

It was a critical picture for Rossen, who hadn’t had a solid hit in a decade and hadn’t made a picture that could be mentioned in the same breath as All the King’s Men (1949). In part his low output was due to being blacklisted during the anti-Communist witch hunt of the early 1950s, although finally cleared. But it was as much due to his unusual method of working. “You gamble time which is money,” he said, “because you may work for six months or a year then realize the property is not quite right and your drop the while idea.” That ran counter to the general Hollywood practice where studios would press ahead with inferior product precisely because so much time and money had been spent on it. Rossen’s office was littered with abandoned projects.

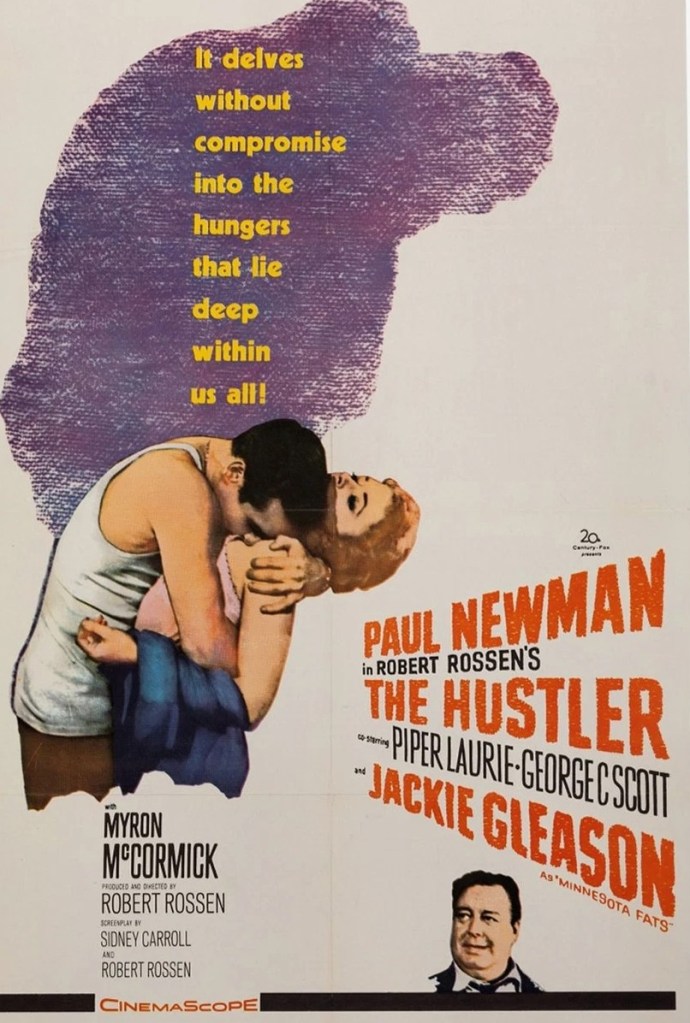

Female lead Piper Laurie was also in the market for a comeback. She had bowed out of the business after Until They Sail (1958) – also starring Newman – fed up with ingénue parts, although the director had initially favored daughter Carole Rossen (The Arrangement, 1969) for the role. At one point Rossen identified Yves Montand for a top supporting role. Co-star Jackie Gleason (Soldier in the Rain, 1963), known at this time as a television comedy actor, was already a decent pool player and Newman was coached by Willie Mosconi, a fourteen-time world billiards champ. Except for one maneuver the two actors managed to achieve all the shots caught on camera. Newman believed he was good enough to beat Gleason and it cost him $50 to be proved wrong.

George C. Scott, primarily known for his work on the stage, had attracted attention with an Oscar-nominated turn in Otto Preminger courtroom drama Anatomy of a Murder (1959).

The film, budgeted at $2.1 million, was shot on location in New York City in the winter and spring of 1961. “You get certain values,” noted Rossen, “ in New York that you can’t get on the Coast (Hollywood).” The pool scenes were filmed at Ames Billiard Academy, established in 1946, near Times Square and McGirr’s. Other locations included a townhouse on East 82nd St which doubled as the Louisville home of the billiard player Findley and the Greyhound Bus Station in Manhattan even though it lacked a dining area and the one built on the premises confused regular customers.

Rossen spent five weeks of the 10-week schedule on the pool action. Sarah’s apartment, however, was located on a sound stage. The director, under pressure to revive his career and suffering from diabetes, was tough on the crew but went easy on the cast. He hired street thugs as extras to add authenticity. He fell foul of electricians and they fell foul of him after he exposed a blackmail scam whereby the electricians responsible for inspecting the unit complained of code violations when it was the same inspectors who should have ensured everything complied with regulations. .

The part was custom-made for Newman. “I spent the first thirty years of my life looking for a way to explode,” recalled the actor. He found an outlet for that problem through acting and he reckoned for Fast Eddie Felson it was pool. “It was one of those movies when you woke every day and could hardly wait to get to work because you knew it was so good that nobody was going to be able to louse it up.”

Though studio 20th Century Fox did its best to louse it up, originally objecting to the location shoot, looking to cut down the running time, especially telescoping the pool sequences it felt might bore the female audience. Desperate to hold onto his vision, Rossen hired Arthur P. Jacobs, then a top-flight PR honcho (and later producer of Planet of the Apes, 1968), who contrived to set up a celebrity screening where the positive response stopped Fox in its interfering tracks. Due to the Actors Strike the previous year, product was in short supply, so although The Hustler was one of 19 pictures opening in September 1961 it didn’t face tough competition, the biggest movies it contended with were Rock Hudson-Gina Lollobrigida comedy Come September and upscale horror The Innocents with Deborah Kerr.

Reviews were positive although in an editorial Box Office magazine railed against a picture which cinemas could not sell to a family audience for a matinee performance.

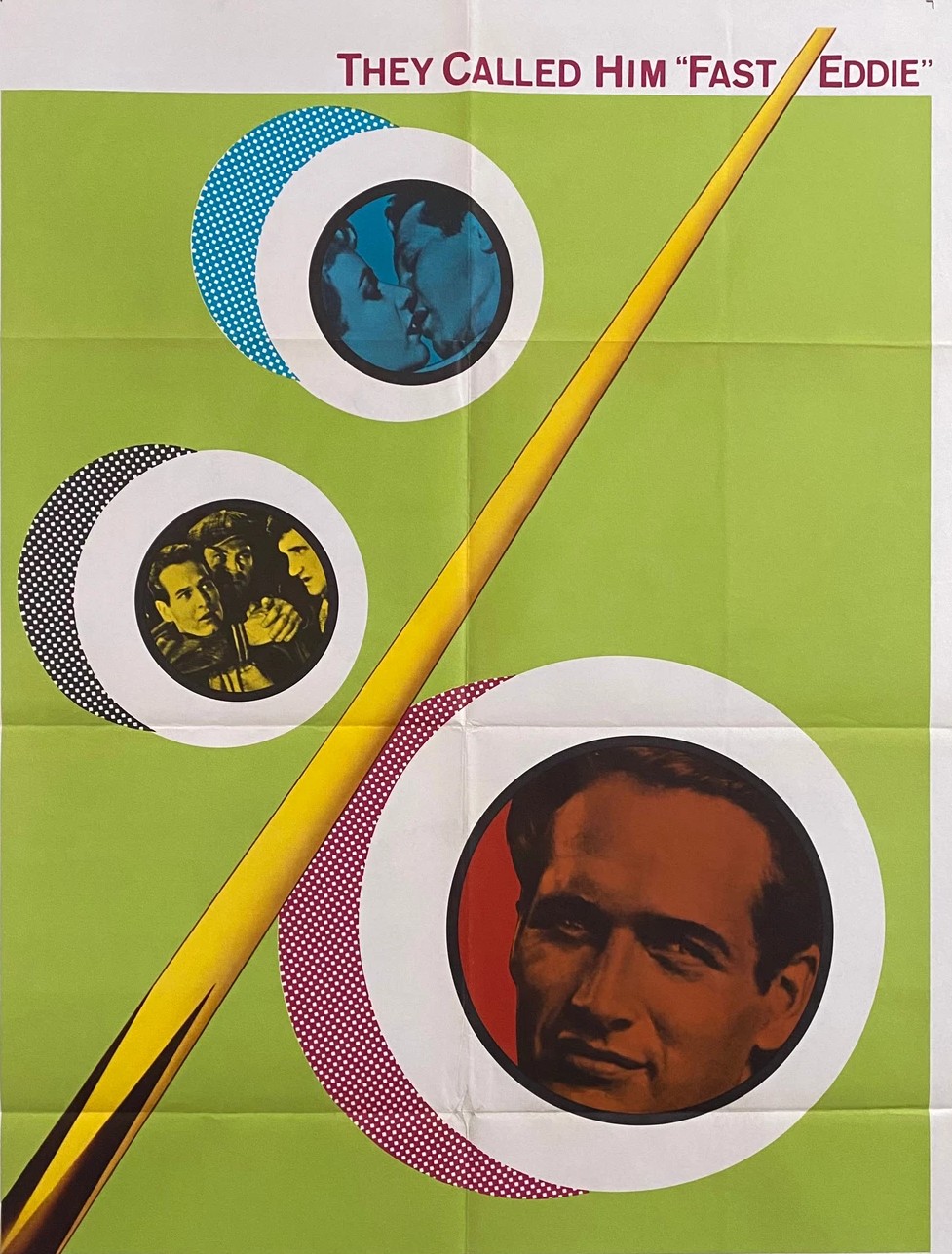

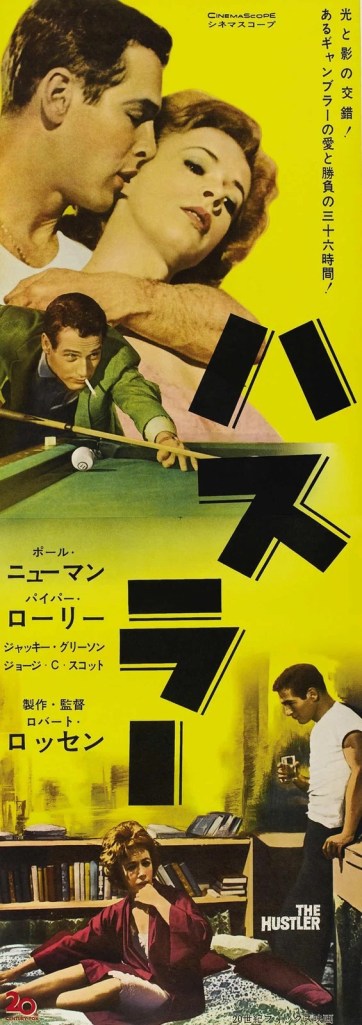

A surprise box office hit, at least initially, in first run in the big cities, The Hustler creamed a “wow” $64,000 in opening week at the 3,665-seat Paramount in New York. There was a “boffo” $36,000 in Chicago, a “fast” $20,000 in Detroit, a “hotsy” $15,000 in Cleveland, a “wow” $14,000 in Pittsburgh and a “smash” $11,000 in Providence. The poster which effectively showed Paul Newman thrusting his head into Piper Laurie’s bosom attracted adverse criticism and caused Chicago newspapers to take a stronger line on movie ads.

It was nominated for nine Oscars with Newman, Laurie, Gleason and Scott all earning acting nods, and Rossen up for two gongs in his capacity as director and producer, as well as potentially sharing one with Sydney Carroll for the screenplay. In the event the only winners were for Eugen Schufftan for Cinematography and Harry Horner and Gene Callahan for Art Direction. At the Baftas it was named Best Film while Newman won Best Foreign Actor and Piper Laurie was also nominated.

Oscar nominations ensured the picture went out on speedy reissue in February and March 1962 resulting in domestic rentals of $2.8 million and a decent run abroad.

Robert Rossen only made one more picture. Paul Newman reconfigured his career and George C. Scott added to his lustre. Jackie Gleason got a shot at top billing with Gigot (1962) but Piper Laurie didn’t make another movie until Carrie (1976).

SOURCES: Daniel O’Brien, Paul Newman (Faber & Faber, 2005) pp79-85; Shawn Levy, Paul Newman, A Life (Aurum, 2009) pp 175-182; Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century Fox, (Scarecrow Press, 2002) p229 and p253; Advertisement, United Artists, Variety, June 24, 1959, p21; “New York Sound Track,” Variety, August 12, 1959, p17; “Gleaned on a Gondola,” Variety, August 26, 1959, p20; “New York Sound Track,” Variety, November 16, 1960, p17; “Fox Nicer to Indies than UA,” Variety, March 8, 1961, p3; “New York Electrical Inspectors,” Variety, March 29, 1961, p5; “Sins of Angels Tag disputed,” Variety, March 29, 1961, p7; “Artistic Comeback,” Variety, May 24, 1961, p4; “Skinpix Can’t See,” Variety, October 18, 1961, p17; “Hustler Re-Release,” Box Office, January 22, 1962, pSW8. Box office figures: Variety October-November 1961.