Stream of consciousness reimagining of Marilyn Monroe’s life mainlining on celebrity, identity, mental illness and vulnerability and held together by a mesmerizing performance by Ana de Armas. Director Andrew Dominik’s slicing and dicing of screen shape, occasional dips into black-and-white and a special effects foetus won’t work at all as well on the small screen. Monroe’s insistence on calling husbands “daddy” and letters from a never-seen potential father that turns into a cruel sucker punch, threaten to tip the picture into an over-obvious direction.

A very selective narrative based on a work of fiction by novelist Joyce Carol Oates leaves you wondering how much of it is true, and also how much worse was the stuff left out. As you might expect, the power mongers (Hollywood especially) don’t come out of it well, and her story is bookended by abuse, rape as an ingenue by a movie mogul and being dragged “like a piece of meat” along White House corridors to be abused by the President.

A mentally ill mother who tries to drown her in the bath and later disowns sets up a lifetime of instability. Eliminated entirely is her first husband, but the scenes with second husband (Bobby Canavale) and especially the third (Adrien Brody) are touchingly done, Marilyn’s desire for an ordinary home life at odds with her lack of domesticity, and each relationship begins with a spark that soon fades as she grapples with a personality heading out of control.

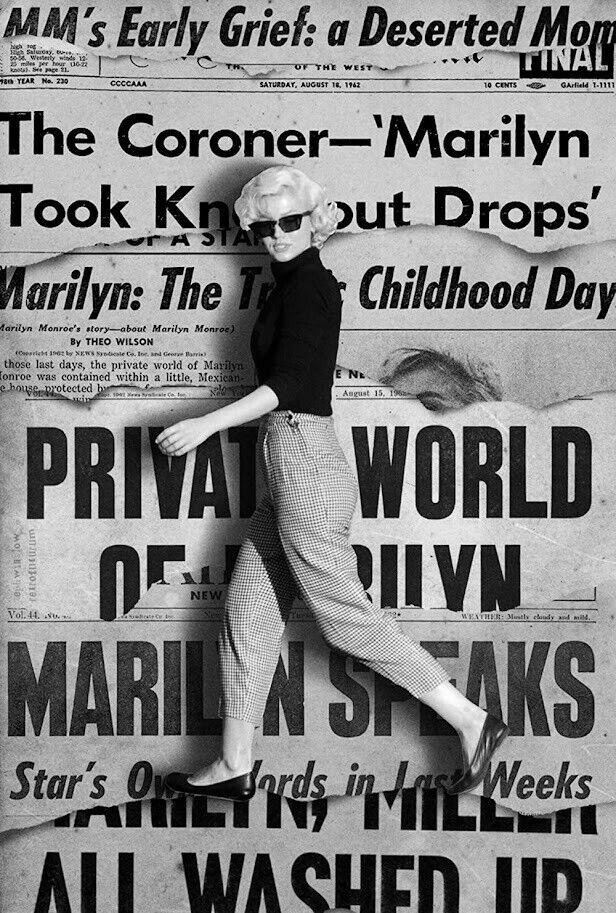

That she can’t come to grips with “Marilyn,” perceived almost as an alien construct, a larger-than-life screen personality that bewitches men, is central to the celebrity dichotomy, how to set aside the identity on which you rely for a living. It’s hardly a new idea, but celebrity has its most celebrated victim in Monroe.

According to this scenario, she enjoyed a threesome with Charlie Chaplin Jr (Xavier Samuel) and Edward G. Robinson Jr. (Evan Williams) but otherwise her sexuality, except as it radiated on screen, was muted. The only real problem with Dominik’s take on her life that there is no clear indication of when her life began to spiral out of control beyond the repetition of the same problems. She remains a little girl lost most of the time.

I had no problems with the length (164 minutes) or with the selectivity. Several scenes were cinematically electrifying – her mother driving through a raging inferno – or emotionally heart-breaking (being dumped at the orphanage) and despite the constant emotional turbulence it never felt like too heavy a ride. But you wished for more occasions when she just stood up for herself as when arguing for a bigger salary for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

I wondered too if the NC-17 controversy was a publicity ploy because the rape scene is nothing like as brutal as, for example, The Straw Dogs (1971) or Irreversible (2002), and the nudity is not particular abundant nor often sexual. That’s not to say there is much tasteful about the picture, and you couldn’t help but flinch at the rawness of her emotions, her inability to find any peace, the constant gnaw of insecurity, and her abuse by men in power.

Ana de Armas (No Time to Die, 2021) is quite superb. I can’t offer any opinion on how well she captured the actress’s intonations or personality, but her depiction of a woman falling apart and her various stabs at holding herself together is immense. The early scenes by Adrien Brody (See How They Run, 2022) as the playwright smitten by her understanding of his characters are exceptional as is the work of Julianne Nicholson (I, Tonya, 2017) as her demented mother. Worth a mention too are the sexually adventurous entitled self-aware bad boys Xavier Samuel (Elvis, 2022) and Evan Williams (Escape Room, 2017).

While there are no great individual revelations, what we’ve not witnessed before is the depth of her emotional tumult. Apart from an occasional piece of self-indulgence, Andrew Dominik, whose career has been spotty to say the least, delivers a completely absorbing with an actress in the form of her life. Try and catch this on the big screen, as I suspect its power will diminish on a small screen.