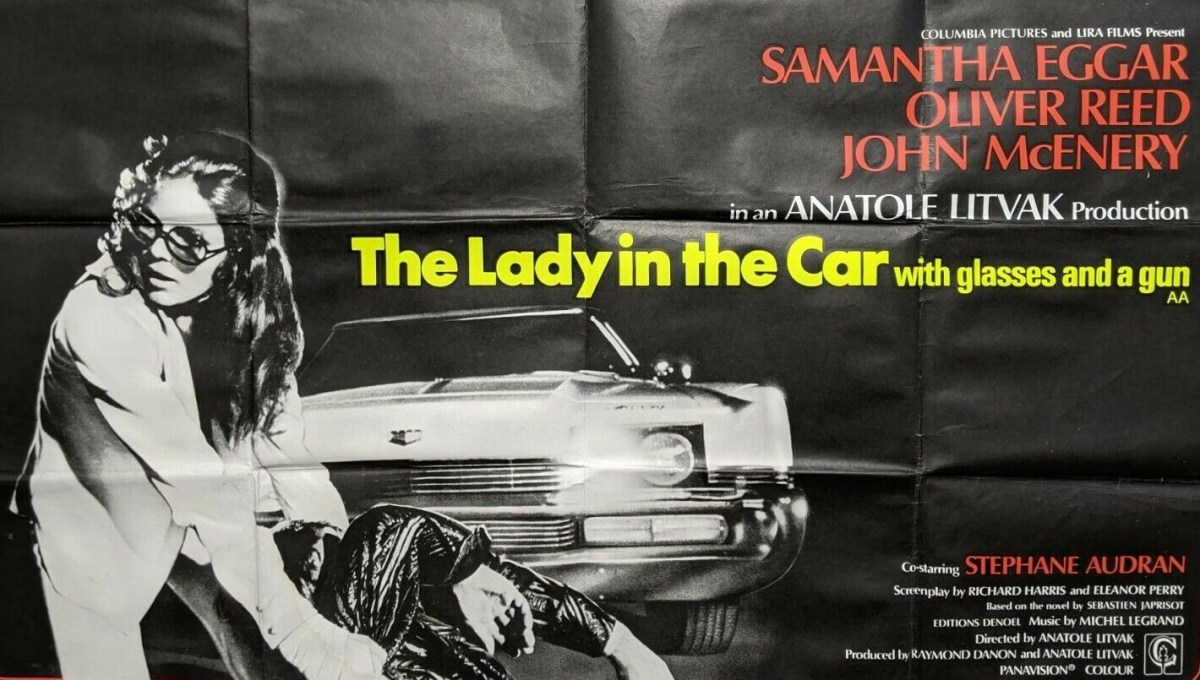

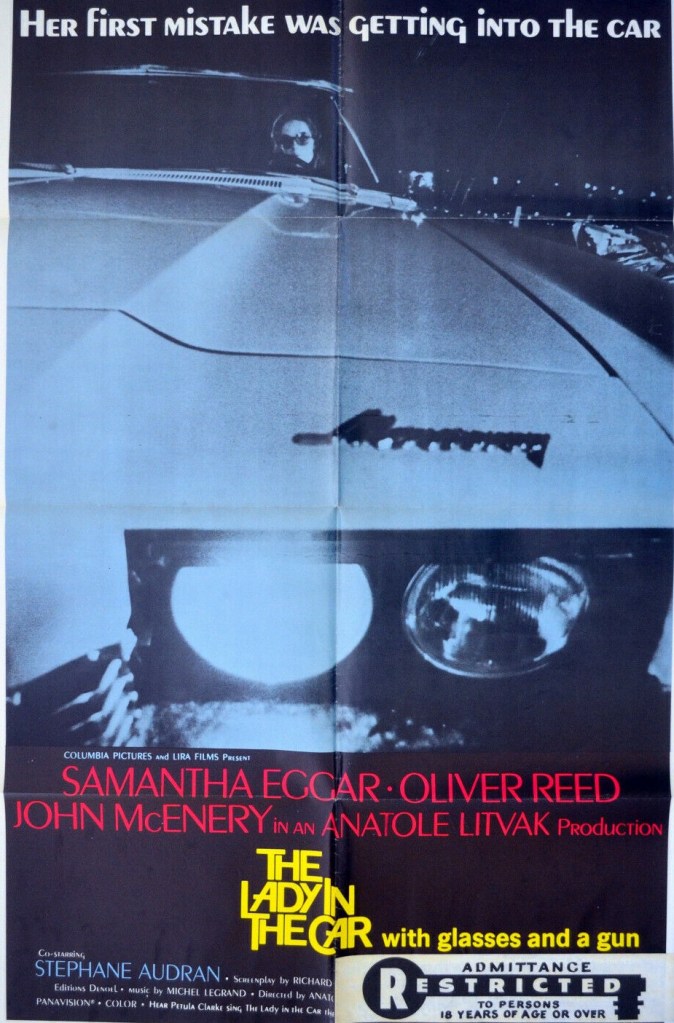

Samantha Eggar (The Collector, 1965) in her first top-billed role and an adapatation of a novel by French cult item Sebastian Japrisot (Adieu L’Ami/Farewell Friend, 1968). You couldn’t get a better mix.

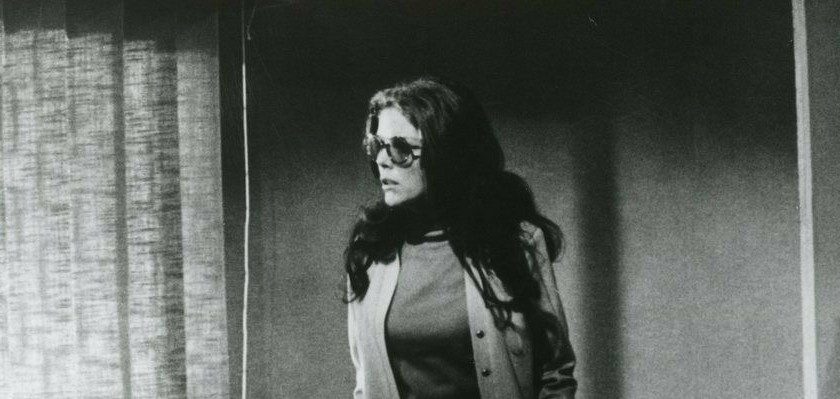

Fashion photographer Danielle (Samantha Eggar) sets off on road trip from Paris to the south of France only to discover everywhere she goes a doppelganger has been there first. She’s on edge anyway because she’s “borrowed” the car of employer Michael (Oliver Reed) and once police start recognizing her she gets jumpier still. The discovery of a body in the boot and the titular gun (a Winchester rifle) don’t help her frame of mind. But instead of reporting the corpse to the police – she’s a car thief after all – she tries to work it out herself. Amnesia maybe, madness because she keeps having flashes of memory – a spooky surgical procedure – or something worse?

She’s got a battered hand she doesn’t know how. Michael’s wife Anita (Stephane Audran) says she’s not seen Danielle in a month though she is convinced she stayed with the couple the previous night. A drifter Philippe (John McEnery) starts helping her out. Eventually she ends up in Marseilles none the wiser.

It’s a tricksy film and like Mirage (1965), recently reviewed, being limited to her point of view means the audience can only work out everything from her perspective. The string of clues sometimes lead back to the original mystery, other times appear to provide a possible solution. The explanation comes in something of a rush at the end.

Despite being the first top-billed role for Samantha Eggar (Walk Don’t Run. 1966), she would not scale that particular credit mountain again until The Demonoid (1981) but she is good in the role of a mixed-up woman struggling with identity. But since it’s based on a novel by Sebastian Japrisot (The Sleeping Car Murder, 1965) there’s a sneaky feeling a French actress might have been a better fit. Oliver Reed (Women in Love, 1969) is not quite what he seems, a difficult part sometimes to pull off, but he succeeds admirably.

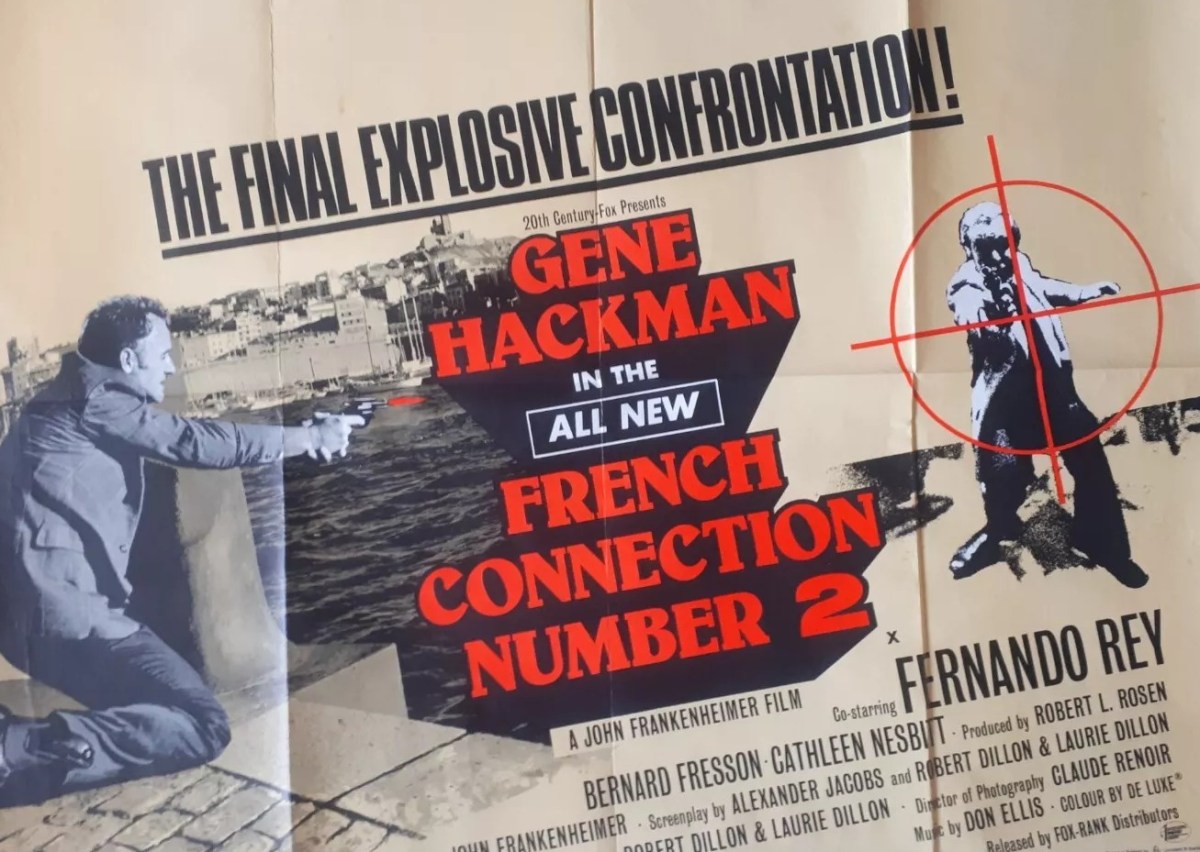

Stephane Audran (Les Biches, 1969), jealous of Danielle, a friend whom she views as a rival for her husband’s affections, has the most intense part, using Danielle as an unwitting cover for betraying Michael. John McEnery (Romeo and Juliet, 1968) could almost be a London spiv, blonde hair, impecunious, clearly using women wherever he goes. Watch out for French stalwarts Marcel Bozzuffi (The French Connection, 1971) and Bernard Fresson (The French Connection II, 1975).

There’s certainly a film noir groove to the whole piece, the innocent caught up in a shifting world, and that’s hardly surprising since director Anatole Litvak began his career with dark pictures like Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) while previous effort Night of the Generals (1967) also involved murder. Litvak and Japrisot collaborated on the screenplay.

I expected a project laced with more atmosphere and a host of original characters. In truth, this is less atmospheric than the other two Japrisot adapatations , the interplay between the characters not so tightly woven, nor the climax so well-spun but it was enjoyable enough.

There was a remake in 2025 starring Freya Mayor (The Emperor of Paris, 2018).