The stars aligned and with only a couple of minutes between features I was able to squeeze in a record-equalling four movies in a single day (excepting all-nighters of course) at the cinema and with one exception they were all well worth the ticket price.

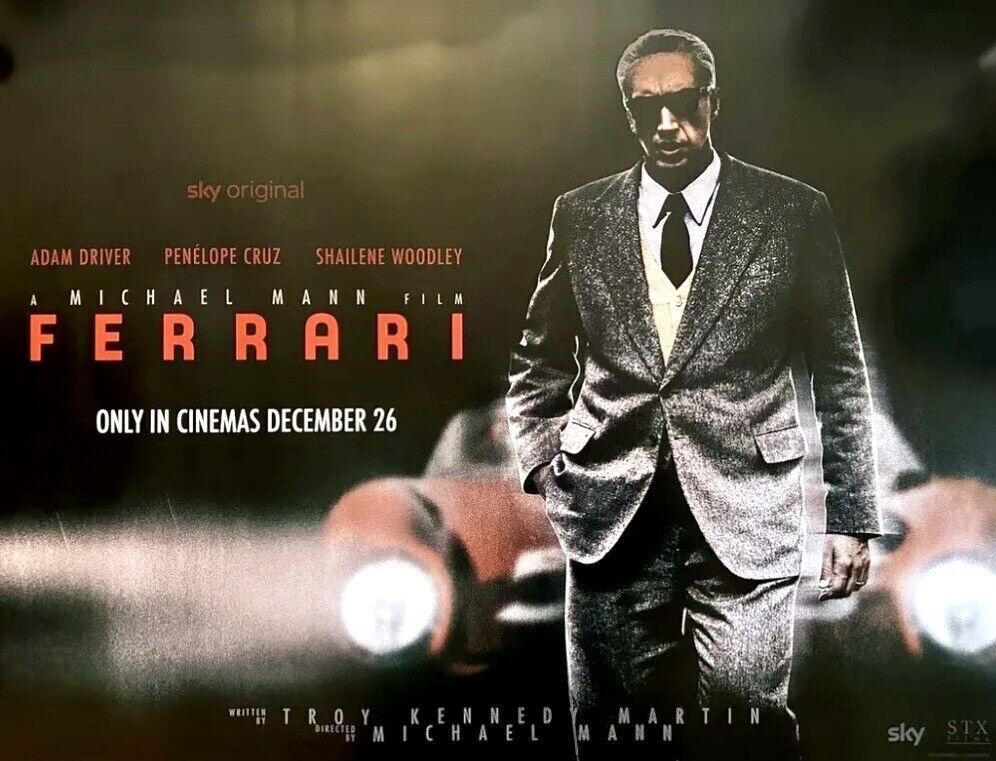

Ferrari

Not really a motor racing picture in the mold of Ford v Ferrari / Le Mans ’66 (2019) or Rush (2013) but more of a domestic drama centering around a dramatic race. The acting is plum, Penelope Cruz (The 355, 2022) taking the honors ahead of Adam Driver (House of Gucci, 2021) though Shailene Woodley (The Last Letter from Your Lover, 2021) seems miscast. The climactic race doesn’t carry the punch of Le Mans, however, the focus more on the backseat players than the drivers. And it’s not quite prime Michael Mann (Heat, 1995)

Set about decade before Ford v Ferrari, it finds Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver) coping with the death the year before of his only son, the potential collapse of his business, and trying to conceal long-standing mistress Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley) from long-suffering wife Laura (Penelope Cruz).

The depth of the couple’s despair at the loss of their son can be measured in the fact that every morning they take flowers, separately, to his graveside. He has at hand an immediate substitute, having fathered a boy, now approaching ten years old, with his mistress, but rejects the chance to officially gave the boy his name.

The manufacturing side of the business was always viewed as merely a way of financing the racing, Ferrari having been a driver earlier in his life. But overspending or lack of income, such details are not specified, has pushed the business towards bankruptcy and he toys with inviting a merger with a bigger company such as Fiat or Henry Ford (which formed a central plank of Ford v Ferrari). But the easiest way out is to win Italy’s most prestigious race, the Mille Miglia, a four-day 992-mile event that ran clockwise across public roads from Brescia to Rome and back.

But I had to look that up. Unlike Le Mans, unless you are a racing aficionado, this doesn’t immediately click in the public consciousness. And there were a host of other details that seemed to skimp on information. Unlike Ford v Ferrari where you learned exactly how fast cars got faster and what it took to drive them or be driven in one (witness Henry Ford’s terrifying hurl), here you are only given some vague technical data which makes little sense. There is little background fill, Maserati pops up as Ferrari’s chief rival but its inclusion is almost incidental. In fairness, you do get more about the jiggery-pokery of running a business.

Running parallel to the racing venture is the family soap opera, will Laura find out about the mistress and child, will she jeopardize the business out of spite. Once the race starts, it’s hard to keep up. Here the distinct lack of detail hurts the most, although there is one shocking scene.

Engrossing enough but it’ll struggle to fill cinemas.

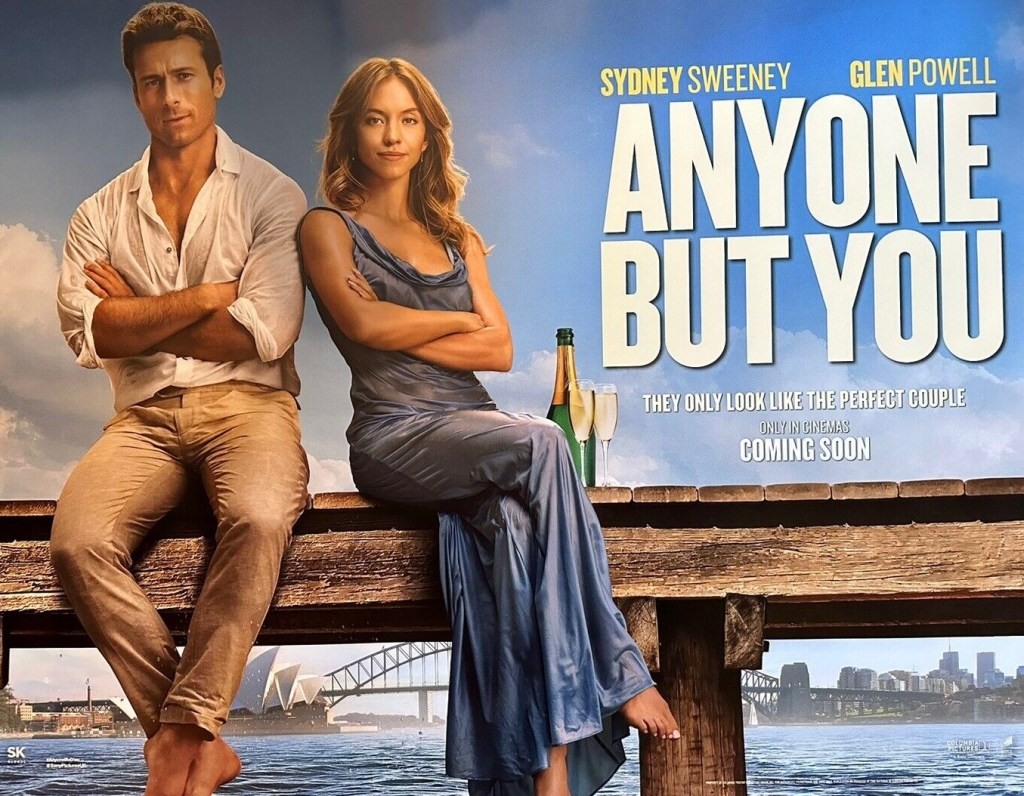

Anyone But You

A contemporary take on the rom-com with the disgruntled participants of a one-night stand forced to pair up at a wedding where they encounter an abundance of exes and various interfering family members. Glen Powell, star in the making in Top Gun: Maverick (2022), comes good as does Sydney Sweeney (The Voyeurs, 2021). Skipping the raw rudeness of its immediate predecessors, this pivots on charm, but with a few helpings of humiliation (he strips naked to avoid a predatory spider) and slapstick thrown in, plus some old-style determinedly un-woke action from one parent in particular. He is the more vulnerable, a poor swimmer, requiring a soothing song to fly. The plot is over-plotted and occasionally it seems some incidents have come straight from Room 101, but generally it works. Probably it helps, if I’m permitted of offer such a comment, that they are A-grade beefcake and cheesecake, respectively. Setting that aside, they appear to have mastered the lost art of the rom-com and certain drew appreciative laughter from the audience I was part of. the kind of film that in the olden days would have picked up a sizeable audience on DVD and turned into the kind of cult that guaranteed a return joust.

One Life

A film of two halves when it should have been divided into three-quarters and one-quarter or an even stiffer division. Concerning the efforts of the “British Schindler” Nicholas Winton (Johnny Flynn playing the younger version, Anthony Hopkins the older) to smuggle out of Prague over 600 Jewish children at the outbreak of World War Two. The earlier section is far more gripping and the later section that revolves apparently around an attempt to publicize the previous rescue in order to highlight the plight of later refugees falls mostly flat on its face as it seems more intent on glamorizing the actions of a man who wanted anything but public recognition. Too much time is spent pillorying a society that sanctified such inanities as the long-running That’s Life television program when I felt it would have been more sensible, and fair, to devote more attention to the work of Winton’s collaborators. While the climactic scene where Winton meets, as grown-ups, the children he saved is moving, it feels redundant compared to the actual children-saving.

Next Goal Wins

Eventually, it turns into a feel-good picture but for most of the time seems intent on making fun of Samoans carrying the tag of the world’s worst team. Nobody seems to ask why FIFA is so determined to bring football to countries where there is no interest in the game. Oddly, Michael Fassbender turns in his most accessible performance as the coach drafted in to improve the team, a big ask since he has clearly been a flop at his chosen profession. You could have pinned the movie more easily on the transgender player more accepted in Samoa than virtually any other country in the world who, by default, becomes the first transgender to play in the World Cup.