Like many an ambitious – not to say greedy – actor, Gregory Peck had decided to go into the production business. In theory, there were two good reasons for this: actors could take control of their careers and they could make vanity projects. In reality, there were other over-riding reasons: after years in the business they thought they knew better than their Hollywood bosses and, more importantly, with a bigger stake in a picture they thought they could make more money. First of all came the tax advantages. As a producer, they could spread income over a number of years rather than just one. And they could take advantage of a loophole in the tax laws by making movies abroad. And then if all went as well as the actor imagined, they would get a bigger share of the spoils. If it proved a flop, then the studio carried the can and the actor walked off scot-free.

In 1956 Peck set up Melville Productions with screenwriter Sy Bartlett, with whom he had worked on Twelve O’Clock High (1950). They signed a two-picture deal with United Artists, the go-to studio for actors wanting to become producers. The first projected ideas fell by the wayside, Affair of Honor based on a Broadway play that subsequently flopped and Thieves Market – with William Wyler on board as director – whose commissioned script didn’t meet Peck’s standards. Also on the agenda was Winged Horse with a script by Bartlett and James R. Webb.

Instead, Peck set up The Big Country (1958) through another production shingle, Anthony Productions, and co-produced it with director William Wyler’s outfit, World Wide Productions. The budget rocketed from $2.5 million to $4.1 million, which limited the potential for profit.

Melville Productions launched with Korean War picture Pork Chop Hill (1959). When that flopped it was the end of the UA deal. Peck moved his shingle to Universal. The production company lay dormant while Peck returned to actor-for-hire for Beloved Infidel (1959) and On the Beach (1959), both flops, before jumping back into the top league with the biggest hit of his career The Guns of Navarone (1961) directed by J. Lee Thompson.

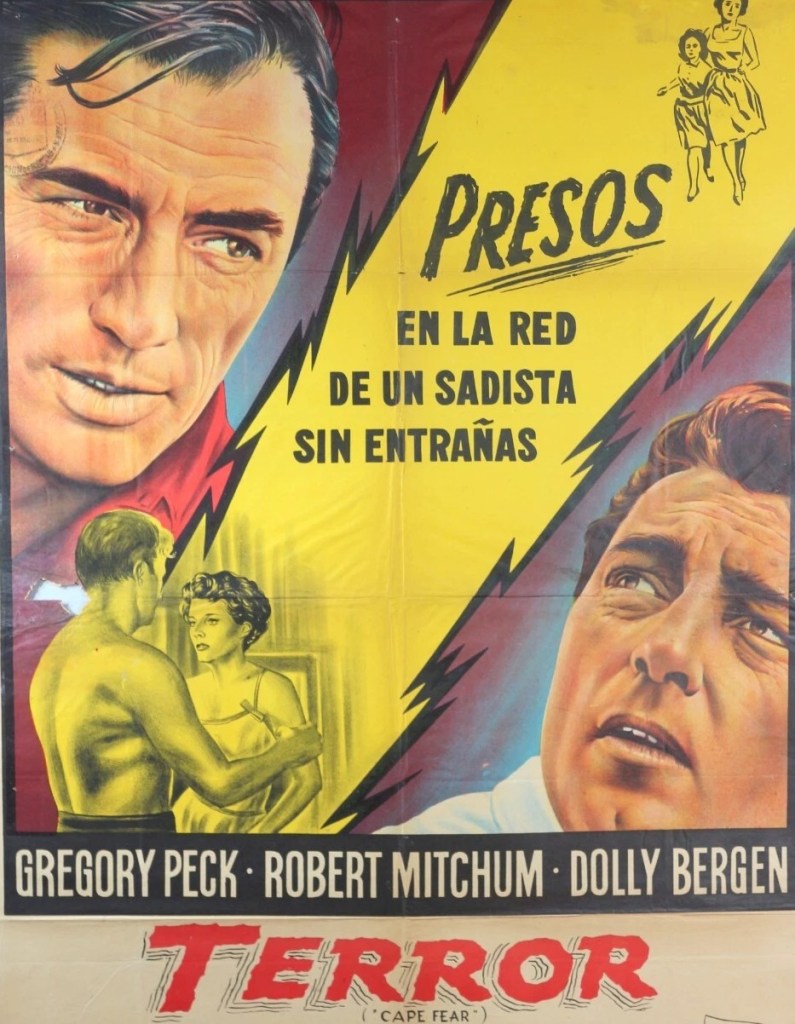

Melville Productions was resuscitated for Cape Fear. Peck and Barlett had purchased in 1958 a piece of pulp fiction (novels that bypassed hardback publication and went straight into paperback) by John D. MacDonald called The Executioners. Bartlett passed on screenwriting duties which were handed to James R. Webb (How the West Was Won, 1962).

Director and star had bonded on The Guns of Navarone. “We were working so well together,” recalled Thompson that when Peck handed him the script of Cape Fear he was intrigued. “I liked the book very much,” said Thompson. “Greg had a script prepared, we signed the contracts, and I came to make my first picture in Hollywood.” (The Guns of Navarone had been filmed in Greece and London).

Though author John D. MacDonald had written a hard-boiled thriller with a merciless killer, screenwriter James R. Webb (Pork Chop Hill) racked up the tension and added a thicker layer of predatory sexuality in the vein of Psycho (1960). The final touch was a Bernard Hermann (Psycho) score brimming with menace.

Ernest Borgnine (Go Naked in the World, 1961) was first choice to play psychopathic killer Max Cady. Rod Steiger (The Pawnbroker, 1964), Jack Palance (Once a Thief, 1965) and Telly Savalas (Birdman of Alcatraz, 1962) were also considered. “We actually tested Savalas and he gave a very good test for the part,” explained Thompson. “But these were character actors or at least secondary actors compared to Greg. At some point discussing it together we began to talk about having the villain played by an actor of equal importance, making it a much stronger match-up from the audience’s point of view and (Robert) Mitchum immediately came to mind.”

But Mitchum had essayed a similar venal character in Night of the Hunter (1955) and didn’t want to repeat himself. However, he liked the way the tale showed just how corrupt law enforcement could be and how easily the cards were stacked. Mitchum understood the character from the outset. “The whole thing with Cady is that snakelike charm. Me, Officer, I never laid a hand on the girl, you must be mistaken.”

“When we heard Mitchum’s thoughts,” noted Thompson, “we were more convinced than ever he would be terrific for the role. And I think by the end of the meeting he now realized that himself.” But he still held back, unsure. The producers sent him a case of bourbon. He drank the bourbon and signed up. There was the additional inducement of sharing in the profits by being made a co-producer which involved nothing more taxing than signing on the dotted line. Universal took it on as the first in two-picture deal with Melville.

Mitchum’s career was following its usual up-and-down course, a couple of flops always seemed to be followed by a big hit. His acclaimed performance in Fred Zinnemann’s The Sundowners (1960) had offset The Night Fighters / A Terrible Beauty (1960) and Home from the Hill (1960). His latest picture, The Last Time I Saw Archie (1961) was filed in the negative column.

Peck and Mitchum had opposite approaches to their profession, the former diligent and serious, the latter not able to get off a set quickly enough, not even bothering to learn his lines because thanks to a photographic memory he could scan his lines just before a scene began and be word perfect.

Locations were scouted in the Carolinas where MacDonald had set the book, but failing to find anything suitable exteriors were switched to Savannah in Georgia. Where Peck rented a house and went home every night, Mitchum took a room in the DeSoto Hotel and when work was finished for the day went out drinking, an assistant director taken along as ballast to keep him out of trouble. The town held bad memories for Mitchum. Last time he had visited he had been arrested for vagrancy and did a stint on a chain gang, which recollection possibly put steely bitterness in his portrayal of the ex-convict. Although he hated the town, he liked the idea that on his return everyone was kowtowing to the big movie star, including a bevy of hairdressers in town for a convention.

Fortunately, the Savanah sojourn was short, bad weather getting in the way, barely two weeks before the unit repaired to Hollywood (some of the boat scenes were filmed around Ventura but the climactic fight took place on the studio lake) where the production overshot its schedule by a month, wrapping on July 5 instead of June 8, and racking up $2.6 million in costs.

Mitchum appeared determined to demonstrate quite how different their approaches were. In one scene, off camera, Mitchum stripped naked to get a reaction from the stolid co-star, who remained immune to such provocation. In reality, Mitchum was very professional. “He would work perfectly,” said Thompson. “He just goes in and does it. He was superb.”

Though far from a Method Actor, Mitchum was chillingly close to the part. “I live character and this character drinks and rapes,” he confessed. During the scenes of violence he worked himself up. “He made people frightened,” acknowledged Thompson.

And that included Peck, especially during the slugfest in the water which took nearly a week of a night shoot to complete. Despite warmers being put in the water, it was freezing. “Sometimes, Mitchum overstepped the line,” said Thompson. “He was meant to be drowning Greg and he really took it to the limit…but Peck never complained.”

The final scene filmed was the rape of Polly Bergen playing Peck’s wife. Bare-chested and sweating, Mitchum built himself up into a fury. “You felt any moment he would explode,” said Thompson. “But there was no rehearsal, so nobody really knew what to expect. Thompson improvised the business with the eggs. But Mitchum was more brutal with the eggs than could ever be shown in a cinema, smearing the yolk over Bergen’s breasts. He cut his arm flailing wildly and he used the actress to break open the cabin door, so she finished the scene with the front of her dress sodden with egg yolk and the back covered in blood.”

While Peck expressed confidence in director J. Lee Thompson and could count on Mitchum’s experience to see him through, female lead Polly Bergen was making her first film in eight years, after a small part in western Escape from Fort Bravo (1953) starring William Holden. She had come to wider attention for winning an Emmy for The Helen Morgan Story (1958).

“Greg spent an enormous amount of time with me,” said a nervous Bergen, “He was wonderful and he was very, very supportive.” She added, “I wouldn’t have let anyone know how insecure and frightened I was. But he, I think, knew that instinctively and was there to set me at ease and be helpful and nurturing.”

Peck had no worries about Thompson, the situation helped by the director appearing to take the line the producer-star wanted. When it came to editing, Peck played fair with Mitchum, resisting the temptation to tone down his co-star’s performance which threatened to overshadow his own.

The censors were livid. They eliminated all mention of the word “rape”, removed most of Mitchum’s ogling of Peck’s daughter and cut to the bone the sexual assault.

While critics tended to agree that Mitchum stole the show, the movie was mauled by the New York Herald-Tribune as a “masochistic exercise” and the New Yorker took Peck to task for becoming involved in “an exercise in sadism.”

Initially, it appeared to be doing well enough. There was a “big” $37,000 in New York, a “giant” $29,000 in Chicago, a “fancy” $14,000 in Cleveland, a “rousing” $18,000 in San Francisco and a “proud” $14,000 in Boston. But the “expectancy of lush performance” did not materialize. Final tally was $1.6 million in rentals, a poor 47th in the annual box office rankings, so there were no profits for Peck or Mitchum to share.

The British censor demanded five minutes of cuts. Thompson made headlines by claiming that 161 individual cuts, a record, had destroyed the film but censor John Trevelyan argued it was just 15. Despite claiming the movie would not be shelved until the controversy had died down, in fact it lost its May 1962 premiere slot at the Odeon Leicester Square in London’s West End and was held back until the following January when it opened at the less prestigious Odeon Marble Arch, setting a record for a Universal release. Bergen was furious at the cuts in her role. “I really blasted British censorship.”

Ironically, Peck made more money from selling the rights to Martin Scorsese for the 1991 remake, in which he had a small part, and whether it’s the Peck estate or Scorsese who benefits there’s a 10-part mini-series on the way starring Patrick Wilson (The Conjuring: Last Rites, 2025) as the attorney, Amy Adams (Nightbitch, 2024) as his wife and Javier Bardem (Dune, Part Two, 2024) as their tormentor.

SOURCES: Gary Fishgall, Gregory Peck, A Biography (Scribner, 2002) pp197-198, 208, 225-228; Lee Server, Robert Mitchum, Baby, I Don’t Care (Faber & Faber, 2001) p43-437; “Peck-Bartlett Spanish Pic Halts,” Variety, February 13, 1957, p2; “U Gets Melville Pair,” Variety, July 29, 1959, p18; “U Repacts Bartlett,” Variety, September 28, 1960, p4; “Director of Cape Fear Claims British Censor Demands Too Many Cuts,” Variety, May 9, 1962, p26; “Censor Replies to J. Lee Thompson,” Kine Weekly, June 28, 1962, p6; “Classification-Plus-Mutilation,” Variety, December 19, 1962, p5; “Your Films,” Kine Weekly, February 7, 1963, p14. Box Office figures: Variety April-May 1962 and “Big Rental Pictures of 1962,” Variety, January 9, p13,

Brian, it’s always good to read your behind-the-scenes write-ups of the movies. For me it adds to the movie viewing experience.

Here’s a little more on Robert Mitchum being arrested for vagrancy in 1932, when he was fourteen years old, just shy of fifteen. He was sentenced to ninety days on a road gang in Georgia. One morning, Mitchum decided to make a run for it. The guard got off a few shots as Mitchum disappeared into the swamp. He swam, crawled, and walked his way to freedom after he crossed the river into South Carolina. He collapsed from exhaustion in a weed patch where he was found by two young girls. They brought him to their home, fed him and cleaned his clothes. When he regained his strength, he headed for home, which at that time was in Delaware. While filming CAPE FEAR twenty-nine years later in 1961, Mitchum quipped, “I wonder if I’m still wanted here by the authorities for escaping and not serving the rest of my sentence.”

Concerning when Mitchum stripped naked to get a reaction from Gregory Peck his stolid co-star, who remained immune to such provocation. Finally, Mitchum’s curiosity got the better of him, and he asked Peck why he didn’t look at him. Peck grinned a slow, expansive smile, “Because of the condition you were in, I was afraid you might f____ me!”

The above information, I found in THEM ORNERY MITCHUM BOYS: THE ADVENTURES OF ROBERT & JOHN MITCHUM(1989) written by John Mitchum. I think it’s a very entertaining book. The part about Mitchum wondering if he was still wanted, I can’t remember where I read it, but I read it somewhere.

CAPE FEAR was a violent movie for its time, the early 1960’s. The movie was distributed by Universal-International and Universal movies were licensed to NBC-TV for prime-time network premieres in 1967. Fact is, all Gregory Peck’s Universal Picture releases of the 1960’s received prime-time TV premieres, except CAPE FEAR. Robert Kasmire, NBC-TV vice-president who supervised program standards said, “In some cases we will turn down a movie because it is too violent for home viewers.” Anyway, CAPE FEAR starring Gregory Peck, Robert Mitchum, and Polly Bergen was rejected by NBC-TV. So, Universal Pictures licensed CAPE FEAR to local TV stations for showing. In 1968 the movie began appearing on local TV stations, usually on a late movie, but not always. In my neck of the woods, it was shown on late movies, not during the evening. Well, needless to say, times have changed.

+

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating stuff, Walter. He was a tricky customer, was Bob. I didn’t know NBC was frightened of showing it, but going out on the midnight circuit probably made it a bit of a cult.

LikeLike