Self-important essay on the self-entitlement of journalists who see themselves as victims, hated by the authorities whose activities they expose and hated by the public for being so cold-blooded – it opens with a television cameraman getting footage of dead people in a car crash before phoning for an ambulance – and for filming stuff that genuine victims did not want filmed.

Filmed in cinema verite style and covering much of what went down in Chicago 1968 when demonstrators clashed with police and the National Guard and tanks rolled through the streets. Certainly strikes a contemporary chord when filming is an universal pastime and many criminals have been brought to book and various issues highlighted by social media.

As if making its point about action and controversy versus talking heads, the movie begins with talking heads, discussing the role of television and journalism in society, with cameramen telling stories of occasions when the public they were trying to help turned on them. The narrative is slight, following television cameraman John Cassells (Robert Forster) going about his business, and betraying girlfriend Ruth (Marianna Hill) with single mother Eileen (Verna Bloom). John is fired after objecting to his television station handing over to the cops and the F.B.I. footage he has filmed of demonstrations and incidents.

Because of the documentary style, much of what has been filmed carries particular resonance as a sign of the times, not so much the police violence because that is widely available elsewhere, but simpler scenes that seem far truer to life. Eileen’s son Harold (Harold Blankenship) is interviewed by an off-screen canvasser about his home life, age, brothers and sisters and so on. Questioned about his father, he explains his father is not at home. “Where would I find him?” asks the interviewer. “Vietnam.”

The boy’s mother Eileen, a teacher who has to manage five grades in one classroom, and John are skirting round the physical side of their romance until jokingly John takes the plunge. “I know your husband’s not going to come charging through the door.” “Buddy’s dead.” The director could already have delivered this information to the audience in talking-heads-fashion but this carries probably the biggest dramatic punch in the picture. This family provides a solid core for a movie which makes its points in more hard-hitting style.

Questions of respect and ethics loom large. Making no bones about finding audience-grabbing material, John is disgusted that people steal hubcaps and the radio antenna from his car when clearly he feels news journalists should be given more respect. But that the public hold an opposite view is clear from Ruth who instances turtles filmed going the wrong way after nuclear explosion distorted their instincts and they went inland to lay their eggs (where they would die) rather than out to sea. She complains that none of the cameramen present thought to turn the turtles round and show them the correct way.

A plot point allows Eileen and John to mingle with the demonstrators during the actual Democratic Convention. There is a shock – and ironic – ending in which John is himself photographed by a passerby after being involved in an accident.

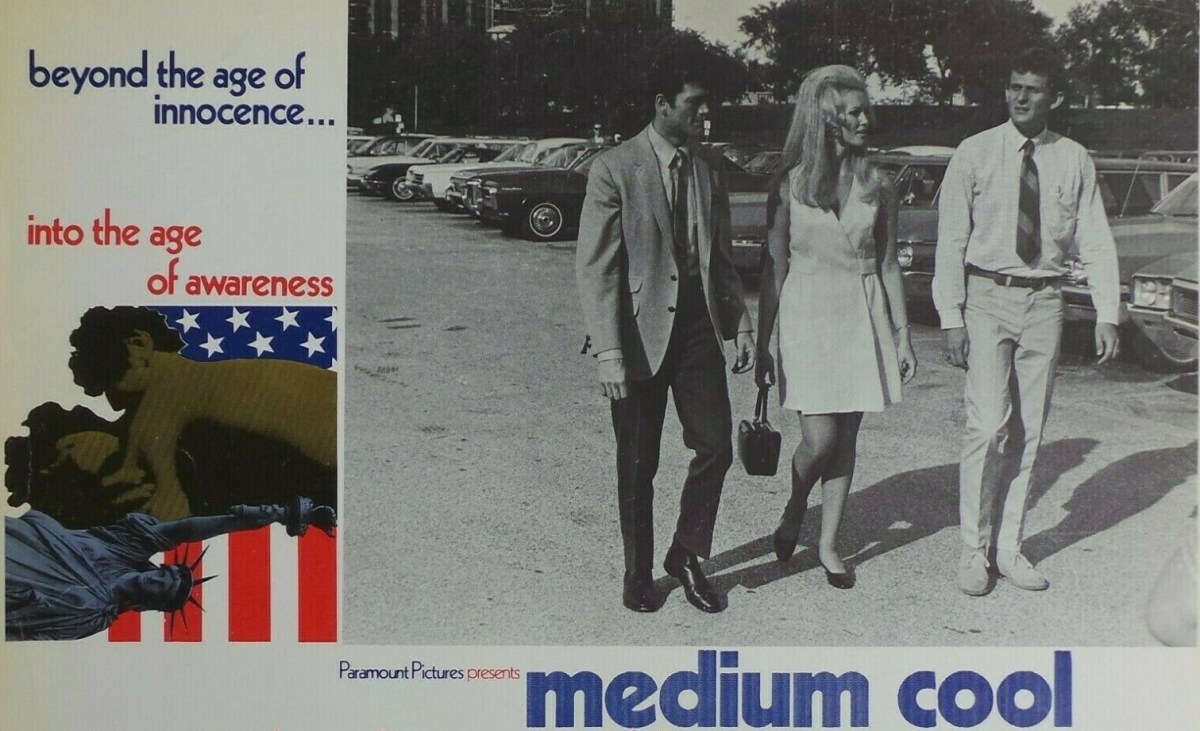

Robert Forster (Justine, 1969) carries off the arrogant victimized reporter well and in her debut Verna Bloom (High Plains Drifter, 1973) is excellent as the real victim of the system while Mariana Hill (El Condor, 1970) raises the tempo as the volatile girlfriend. Peter Boyle (Taxi Driver, 1976) has a small part.

Oscar-winning cinematographer for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966), Haskell Wexler (who also wrote the script) makes a notable debut as director, mixing fact and fiction, taking a political stance and introducing a revolutionary camera technique. Half a century on, not much has changed in attitudes to media ethics although it is another photographic revolution via social media that is leading the discussion in what takes top billing in terms of news. Its content has led the film to be seen as a landmark of the cinema.

This absolutely passes my test; does it say anything about the time it was shot? In fact, it’s one of the best examples of mixing fact and fiction artfully. Went to see Wexler talk in Edinburgh, and he was able to break down the spontaneous moments that they caught on camera. Would like to see 10 films a year like this….

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a good time to capture the spontaneous. He could easily have sanctified journalists and may well have done had it come out a few years later after All the President’s Men. Did a very good job of making journalists human.

LikeLike

Here is something:

“Documentary filmmaker and cinematographer Haskell Wexler initially set out to make Medium Cool as a screen adaptation of Jack Couffer’s as-yet-unpublished novel, The Concrete Wilderness. Wexler used his own money to finance the production, which marked his narrative motion picture writing and directing debut, as part of a “negative pickup deal” with Paramount Pictures, under which Paramount promised to pay him $600,000 for the finished film, as noted in a 6 Dec 1968 DV article. A 22 Mar 1967 DV item had previously stated that Buzz Kulik would produce and direct, from a screenplay written by Jack Couffer. Wexler’s script, which centered around a television news cameraman, strayed significantly from the source material and anticipated the incorporation of real-life events, including the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, IL. An article in the 10 Jul 2013 Chicago Reader noted of the adaptation, “The only vestige of Couffer’s novel was a subplot in which the cameraman, John Cassellis, gets involved with an Appalachian boy and his mother in Uptown.” In an interview published in the 28 Oct 1968 LAT, actor Peter Bonerz explained, “We had a script when we started and our intention was to fill the portions involving news events with actual news occasions.” Fortuitously, the filmmakers were present for the history-making demonstrations and ensuing riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Although Wexler claimed in a 7 Sep 1969 NYT interview that the script was completed four months before the convention was scheduled to take place, and that the violence could not have been predicted, there were plenty of indicators that a confrontation might erupt between police and antiwar demonstrators. Wexler also alleged that he and his crew were surveilled by Chicago police, the U.S. Army, and the Secret Service for the seven-week period in which they shot there.

Thirteen-year-old Harold Blankenship, who made his motion picture debut in Medium Cool, was discovered by Wexler in an Uptown neighborhood populated by poor Appalachian transplants. Blankenship’s parents had moved the family there in 1966 and were subsisting on welfare when the boy was cast, according to the Chicago Reader, which also noted that, a few years after filming, Blankenship was orphaned and subsequently moved back to his home state of West Virginia. An entire subplot based in Blankenship’s Uptown neighborhood was shot, but editorial consultant Paul Golding reportedly excised most of it. Deleted scenes were said to include a trip to Washington, D.C., in which real-life activist Peggy Terry and Verna Bloom’s character, “Eileen Horton,” visited “Resurrection City, a muddy tent camp erected on the National Mall by the Poor People’s Campaign.” Terry and Bloom also filmed a scene at an “Operation Breadbasket” gathering, where activist Jesse Jackson gave a speech.

Principal photography began in Chicago on 29 Jul 1968, according to a Var production chart published on 18 Sep 1968. Mid-way through filming, the 26 Aug 1968 DV announced a title change from The Concrete Wilderness to Medium Cool, a term that echoed media theorist Marshall McLuhan’s description of television as a “cool medium,” as indicated in the 31 Aug 1969 NYT. In late Aug 1968, when riots erupted in Grant Park outside the Democratic National Convention, Wexler’s cast and crew blended in with the crowd as much as possible so that people around them were not aware that a movie was being filmed. Wexler, himself, was tear-gassed by National Guardsmen, as noted in the 6 Dec 1968 DV. Ironically, the filmmaker had made an agreement with the National Guard’s training division to provide them with roughly 1,000 feet of film for training purposes, according to the 13 Aug 1969 Var. Throughout production, Wexler claimed he was “constantly harassed by Chicago police and Mayor [Richard J.] Daley’s office.” Other than Grant Park and the International Amphitheatre, where the convention took place, Chicago locations included “a psychedelic discotheque, a roller derby, Chicago’s uptown Appalachian ghetto, Chi[cago]’s fast Expressway, and a gun clinic,” as stated in the 24 Jul 1969 DV review. Location shooting was also done in Kentucky and Minnesota.

Wexler estimated his final expenditures on the production would amount to $800,000, which was $200,000 over the acquisition fee Paramount had promised, according to the 6 Dec 1968 DV. However, Wexler was also set to receive fifty-percent of the profits. According to the deal, Paramount retained the right to “re-edit and add or delete from Wexler’s cut” before releasing the picture.

A 2 Jul 1969 Var brief announced that Medium Cool had received an X-rating from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), due to vulgar language and a love scene showing male and female frontal nudity. An article in the 16 Jul 1969 Var noted that the film contained “liberal use of the most common fourletter word for fornication, as well as the common fiveletter word for the male sexual organ.” The words alluded to were said to “represent the last language barrier” for major studio films, after the recent normalization of “the common euphemisms for urine and defecation” that had been taboo only eighteen months before when heard in the film version of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1967, see entry). The article also pointed out that Medium Cool was “the first major-company American film to contain below-the-waist nudity.”

Critical reception was mixed. However, the picture came to be known as one of the “new American statement films,” as noted in the 21 Sep 1969 LAT review, which deemed it more provocative and important than recent releases like Midnight Cowboy and Easy Rider (1969, see entries). The 28 Aug 1969 NYT review likened it to “a kind of cinematic ‘Guernica,’ a picture of America in the process of exploding into fragmented bits of hostility, suspicion, fear and violence.” It fared well commercially, grossing $1 million in film rentals in the first four months of release, the 7 Jan 1970 Var reported.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great stuff. Thanks once again.

LikeLike