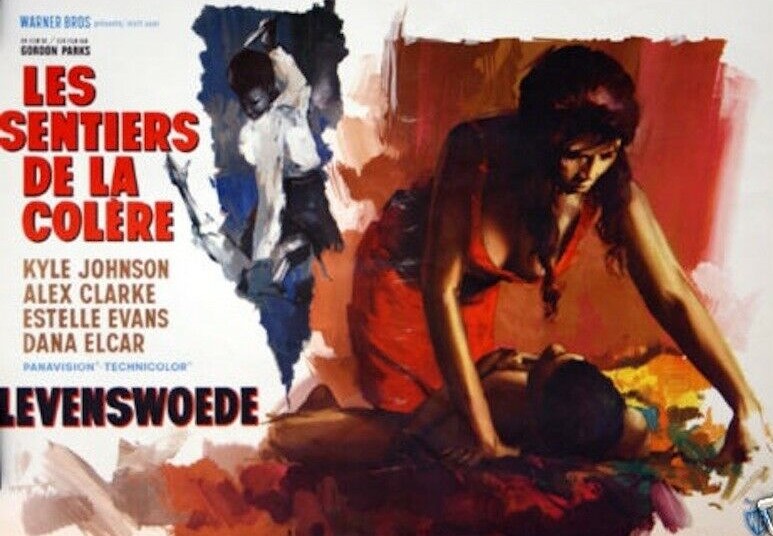

Director Gordon Parks made a big noise a couple of years later with Shaft (1971), Richard Roundtree shooting to fame as a slick and sexy private eye, memorable score by Quincy Jones. But The Learning Tree had possibly a bigger impact on the Hollywood consciousness, the first movie released by a major studio (Warner Brothers) that was directed by an African American. Although actors like Sidney Poitier and Jim Brown had smashed the Hollywood glass ceiling, directors lagged far behind. And this would have been an interesting tale in its own right of adolescence in 1920s Kansas had the leading character Newt (Kyle Johnson) and buddy Marcus (Alex Clarke) not faced such blatant racism.

Told today, the story would take a different route, concentrating on the dilemma of Newt in coming forward with the evidence that could convict Marcus’s father Booker (Richard Ward) of murdering a white man, not just the guilt at sending another African American to the electric chair but fear of the killing spree that must follow from enraged whites. Instead, that aspect comes at the tail end of a story that sees Newt and Marcus react in different ways to white supremacy. It’s not that Newt is spineless, toeing the line, but that Marcus, filled with venom, sees violence as the only way to establish any kind of equality.

When Newt, a reasonable enough scholar, though hardly in the genius class, is marked down by his teacher on the grounds that it’s a waste of time going to college when he will still end up a cook or a porter, the young man responds, “You hate us colored kids, well, we hate you, every one of you.” Marcus has a similar mantra, “this town don’t want me and I don’t want this town.” That underlying endemic racism contrasts with the more overt vicious bullying of local cop Kirky (Dana Elcar) who casually shoots any African American who sensibly runs away at his approach and who ends every sentence with the word “boy.”

What makes this so powerful is that for long stretches there’s just the ordinary coming-of-age tale of Newt falling in love with Arcella (Mira Waters), sneaking a kiss, finding their own special place among the daffodils, buying each other Xmas presents, the romance conducted among summer picnics, winter snow, rowing on the river, the young man showing his beloved every respect even given that he is not a virgin, having unexpectedly lost his cherry while sheltering from a tornado. He has a conscience, too, going to work voluntarily for a farmer whose apples he stole.

It’s not just Newt’s equable temperament that’s prevents him from reacting like Marcus to the unfairness of the white-dominated world. He has the ability to get the best out of situations. A born negotiator he manages to triple the reward offered by Kirky for helping bring up a dead man from a river, and, having been taught to box, earns good money in a match. Marcus goes to jail for beating up a white man who attacked him with a whip and this not being a sanitised version of the African American world on release ends up working in a whorehouse while his father steals a supply of hooch.

Even so this is a hierarchy even a prominent white person cannot overturn. When a judge’s son invites Marcus and Arcella into a drug store, the other two must take their drinks outside.

A staff photographer for Life magazine, director Gordon Parks, adapting his autobiographical novel, avoids the temptation to pack the movie with brilliant images, instead concentrating on core coming-of-age aspects to drive forward the narrative. He doesn’t have to do much to point up the injustice. That’s inherent in the material.

It probably helped that the three young principals were inexperienced, although at the time of course roles for African Americans, except in cliché supporting parts, were hardly abundant. Kyle Johnson (Pretty Maids All in a Row, 1971) was 16 when playing the 14-year-old, Alex Clarke (Halls of Anger, 1970) pushing 20 and making his debut as was Mira Waters (The Greatest, 1977). There’s no straining for dramatic acting effect. Everyone plays it straight.

Others involved are Estelle Evans (To Kill a Mockingbird, 1962), Dana Elcar (Pendulum, 1968), Richard Ward (Black Like Me, 1964) and Russell Thorson (The Stalking Moon, 1968). Not only did Parks write, produce and direct but he supplied the music too.

It’s an absorbing, if at times difficult, watch. It’s an accomplished picture for a beginner. And you can’t help but wondering how four decades after this story takes place little had changed for ordinary African Americans and another five decades after the film’s release the battle for equality has not been resolved.

Great to focus on the less iconic side of Parks. The Shaft films are fun, but they’re far more cartoonish than this…

LikeLike

Some more:

The working title of the picture was Learn, Baby, Learn. Based on his 1963 autobiographical novel, The Learning Tree, it marked the feature film debut of Gordon Parks, who was the first African American staff photographer for Life magazine. With the making of The Learning Tree, Parks became the first African American to direct a major theatrical motion picture. Parks had previously directed “several short film subjects and two one-hour features for National Education Television,” as stated in the 2 Apr 1968 NYT.

The project was five years in the making, according to a 17 Apr 1964 DV item, which reported that the writer-director had begun talks with producers interested in optioning his book. Two independent producers first acquired film rights, the 17 Aug 1969 NYT noted, but they were unable to raise the necessary funds. Another producer allegedly offered Parks $75,000 to adapt the script, with the stipulation that he must rewrite the black characters as white. Parks declined. At some point, Bob Hope’s daughter, Linda Hope, was interested in producing the adaptation, according to a 7 Nov 1968 DV brief, but it was Parks’s friend, filmmaker John Cassavetes, who introduced his work to Ken Hyman, an executive at Warner Bros.—Seven Arts, Inc., which ultimately funded the production. Although Cassavetes accidentally gave Hyman a copy of Parks’s 1966 memoir, A Choice of Weapons, instead of The Learning Tree, Hyman became enthusiastic about working with Parks and reportedly struck a four-picture deal with him within a fifteen-minute meeting. The Warner Bros.—Seven Arts deal was announced in the 1 Apr 1968 DV, which referred to Parks as “the first negro in film history to direct a major feature for a major film company.” Also a well respected musician, Parks was set to write the score, which, according to the 12 Jul 1968 DV, entailed a four-movement symphony. The production budget was set at slightly less than $2 million, the 25 Jun 1969 Var reported, and Parks was slated to receive twenty-five percent of any profits, according to the 19 Oct 1969 LAT.

Principal photography was scheduled to begin on 30 Sep 1968 in Parks’s hometown of Fort Scott, KS, as noted in a 27 Sep 1968 DV production chart. Problems arose when the film crew, including six African Americans, began shooting in the town, as stated in a 7 Nov 1968 DV report which implied that the difficulties arose from racial tension. A later article in the 25 Jun 1969 DV noted that there were twelve black crew members, not six, and blamed the tension between locals and filmmakers on the fact that Fort Scott residents wrongly assumed The Learning Tree was a “dirty film.” Parks said that shooting there eventually worked well, and that the local Elks Club admitted African Americans for the first time at a party thrown for the cast and crew. Parks was given a key to the city by local officials, and “Gordon Parks Day” was declared in early Nov 1968.

Following five-and-a-half weeks in Fort Scott, cast and crew moved to the Warner Bros.—Seven Arts studio lot in Burbank, CA, where another two-and-a-half weeks of principal photography was scheduled, beginning in mid-Nov 1968. On 11 Dec 1968, Var confirmed that filming had been completed.

Although William Conrad acted as executive producer throughout the shoot, his name was removed from the credits, as reported in the 19 Jun 1969 DV. The following week’s Var explained that Conrad had agreed to help but wanted no credit, since The Learning Tree was “Gordon’s story.”

In discussing the small contingent of African Americans on his crew, Parks was quoted in the 17 Aug 1969 NYT as saying, “I hired 12 Negroes to work on the production. It was a fight, because the Hollywood unions are all white, but I got enormous cooperation from Warners.” The studio hired a black electrician, Gene Simpson, for the first time in its history, according to the 13 Mar 1969 Los Angeles Sentinel, which also noted that publicist Vincent Tubbs – the only black union head as the president of the Hollywood Publicists Guild – worked on the film. Parks’s son, Gordon Parks, Jr., acted as still photographer.

The Learning Tree was first screened on 18 Jun 1969 at a Warner Bros.—Seven Arts press junket held in Freeport, Bahamas, as stated in that day’s Var. Following its debut there, the 25 Jun 1969 Var suggested that Parks’s “viewpoint on America and its racial problems” in the 1920s-set film might be negatively received by “black militants and other radical types.” Parks contended that black militants had been purposely planted in preview screenings, and although they had sometimes laughed at inappropriate times, they had generally congratulated him for his accomplishment. Parks stated, “But actually, I don’t care what they think. This is my story. I believe that in the black revolution there is a need for everyone.”

Despite the film’s perceived innocence, it received an M-rating (suggested for mature audiences) from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), as noted in the 16 Jul 1969 Var. It was due to have its world premiere on 6 Aug 1969 at the Trans-Lux East and West theaters in New York City, the 30 Jul 1969 Var announced. Early reviews were mixed. The 10 Sep 1969 Var noted that although Warner Bros.—Seven Arts had initially planned a slow rollout of the film in art house theaters, its success at the more commercial Trans-Lux West – and relative failure at the Trans-Lux East – indicated the picture would play better at larger, inner-city theaters. A new “playoff pattern” was devised to take advantage of its box-office potential at theaters known for action films and other commercial fare. Within seventeen weeks of release, a 5 Nov 1969 Var box-office chart listed a cumulative gross of $1,327,543 in twenty-seven theaters.

At Los Angeles, CA’s Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, where The Learning Tree opened on 20 Aug 1969, a large fiberglass sycamore tree was built around the box office in honor of the film. According to an 18 Aug 1969 DV brief, Warner Bros.—Seven Arts planned to donate the decoration to the Crippled Children’s Society of Los Angeles County after the film completed its run at the theater.

The 23 Jul 1969 DV announced that The Learning Tree would be shown as a U.S. entry at the Edinburgh Film Festival in late Aug or early Sep 1969. In addition to its inclusion in the festival, the film went on to garner many accolades, as noted in various DV items published between Aug and Oct 1969, including National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Image Awards for Best Picture (in a tie with Joanna [1968, see entry]), Best Director, Best Actress in a Feature (Estelle Evans), and Most Promising Young Actor and Actress (Kyle Johnson and Alex Clarke). Parks received an Annual Achievement Award from the Foundation for Research and Education in Sickle Cell Disease of New York City; an Achievement Award from the city of Cleveland, OH, presented to him by Cleveland’s mayor, Carl Stokes, on the night of the 24 Sep 1969 Cleveland premiere; and a Certificate of Merit from the Southern California Motion Picture Council, which also named the film a “Picture of Outstanding Merit.” Twenty years after its release, in 1989, it became one of the first twenty-five films selected for inclusion in the Library of Congress’ newly founded National Film Registry.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can I use this excellent piece? Attributed to you, of course.

LikeLike

If you want to, you can say I found this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As “Fenny100” or by your real name?

LikeLike

My real name.

LikeLike

What is your real name?

LikeLike